Pathways to 2030

Industry emissions are up 15.5% since 2005, driven by U.S. demand.

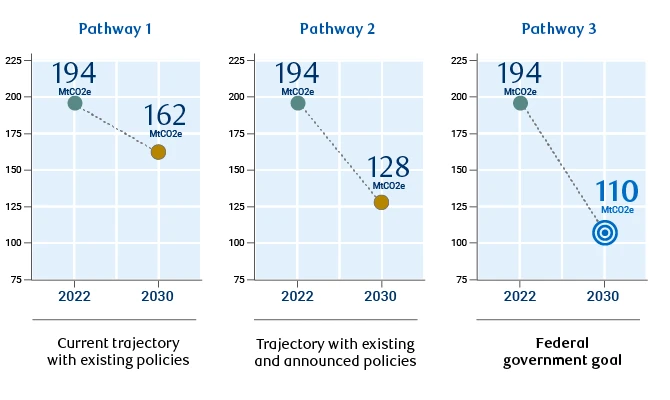

Oil and gas emissions need to decline 43% without compromising Canadian and global energy security.

The Year In Climate Policy

Countries committed to “transition away” from fossil fuels at the UN Climate Summit, or COP28, in Dubai.

A federal oil and gas emissions cap was announced at COP28. If approved, Canada would be the only major oil exporter setting emission limits on its hydrocarbon sector.

New federal draft regulations around methane were also announced during COP28.

Alberta introduced a 12% investment tax credit for carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS), building on Ottawa’s tax credits announced in 2022.

Ottawa allocated nearly half of the Canada Growth Fund $15-billion budget towards Carbon Contracts for Difference (CCfD)—effectively a federal insurance policy guaranteeing carbon prices for large-scale decarbonization projects.

Canadian Oil Emissions Intensity Highest Among Major Producers

kgCO2e/bbl

Source: Carnegie Endowment Oil Climate Index; RBC Climate Action Institute

Three Things To Watch In 2024

Detailed oil and gas emissions cap rules expected by mid-2024.

A 60-day consultation period for draft methane regulations to close in February.

Federally-owned Trans Mountain oil pipeline’s 590,000 barrel-per-day expansion expected to be completed.

CASE STUDY

Digging Deep for Success

Eavor Technologies Inc.

Calgary, Alberta

THE SPARK

Eavor was nobody’s “darling” when John Redfern and his team first pushed their new twist on geothermal technology at Creative Destruction Lab, the University of Toronto’s version of Shark Tank. Even old friends avoided eye contact. “They weren’t rushing for their checkbooks,” Redfern laughs.

That was around 2017, the year Big Oil was jettisoning geothermal assets. Fast forward, and the Calgary-based startup now counts BP Ventures, Microsoft’s Climate Innovation Fund, Singapore-based Temasek and Austria’s integrated energy firm OMV AG, among others, in its roster of investors. Eavor—or “endeavour without end,” as Redfern likes to say—is also Canada Growth Fund’s first investment.

THE CHALLENGE

Geothermal energy could serve as an alternative to expensive nuclear and hydroelectricity to supply relatively cheap, zero-emission baseload power and sustain the electrical grid’s minimum average demand.

While certain countries such as Iceland, New Zealand, Indonesia, and the southwestern U.S. already have projects built and underway, the technology faces several geological challenges.

Traditional geothermal is a risky exploration game that needs a trifecta of hot rock, hot water and pathways for the hot water to flow to the surface to work. Such geological good fortune is rarely available together in most locations.

THE SOLUTION

Eavor’s closed-loop technology helps take these out of the equation. By drilling long, branched wells deep into the ground and using a working fluid to replace the hot water geothermal usually needs, Eavor can harvest the Earth’s perennial heat anywhere and at any time. “There may not be a permeable reservoir, but there are hot rocks, and it gets hotter every kilometre you go down anywhere in the world,” says Redfern. The technology generates zero greenhouse gas emissions, no air pollution, has no continuous water use and boasts a small surface footprint.

Redfern expects geothermal costs to go down similar to other renewables, and its economics are already competitive to natural gas for heat in places like Europe. Geothermal technology can also bring energy security to the grid, something Some European countries are especially keen on after its experience of Russia’s weaponization of its oil and gas.

The U.S. defence industry has already taken note. In October 2023, the U.S. Air Force awarded Eavor and Chesapeake Energy a contract to generate geothermal energy at a San Antonio, Texas, facility. The prototype aims to fortify defence infrastructure and deliver reliable clean energy regardless of electrical grid disruptions.

WHAT’S NEEDED

Eavor secured $182 million in new financing in 2023, bringing OMV AG, Japan Energy Fund, Monaco Asset Management and Microsoft’s Climate Innovation Fund into the fold.

Buoyed by the results, Eavor and Enex Power Germany started building a full scale Eavor-Loop heat and power project in Bavaria, Germany. Even though Germany is not a cheap place to drill, Redfern picked it as the location for the company’s first full scale project due to its high environmental standards, robust regulations and ready-made district heating networks that made it in advantageous place to prove up the technology. Eavor drilled successfully in sites where traditional geothermal drilling had already failed—three times. “A lot of our early adopter sites that we're embracing, are former failed traditional geothermal sites.”

WHAT’S NEXT

Redfern believes the Canadian oil service ecosystem and talent base can emerge as a hive for nurturing new technologies. While it’s tough to raise money in this environment, there is a need for venture capitalists in Canada to start taking risks.

The CEO is also keen to keep Eavor’s intellectual property rights in Canada. Recent examples of promising Canadian clean tech startups being snapped up by international investors that turn Canadian head offices into a branch, serve as cautionary tales.

“We want to make sure that we maintain our IP coverage the way we have, where we can still fully deliver the project and license our technology everywhere,” Redfern said. “But it'd be very easy to lose that money. We've tried to avoid that.”

The first step is to get the Euro-380 million German project to first power. The company has partners in Austria and several other projects at various stages of development in the pipeline. “We are pre-assembling everything ready to go and taking baby steps on all the other projects waiting to ready take off once we get first power.”

Deep Dive

Methane

- Capping methane is the single best near-term option. While investments in carbon capture, utilization and storage is vital in the long run, methane cuts can yield faster results.

- Canada has cut emissions by a third in a decade. Federal and provincial policies and industry innovation have been effective tools in cutting methane emissions.

- Natural gas production could rise 25% by 2030 amid rising demand in emerging markets. New liquefied natural gas shipments could raise methane emissions without adequate abatement efforts.

- Industry needs to invest $15 billion. That would help remove 217 million tonnes of CO2e of methane and associated emissions from 2027 to 2040.

- Undercounting emissions remains a problem. Only seven out of 130 methane abatement projects from major emitting companies are focused on tracking it.

Methane, extracted as natural gas, is at the heart of industrial products and residential and commercial heating that give Canadians one of the world’s highest standards of living. And its abatement may be the quickest way to cut national emissions. In the oil and gas sector, carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) continues to get much of the policy attention, but methane reductions may be an attractive and cheaper option.

The colourless and odourless gas released from oil and gas production, landfills and agriculture is the main component of natural gas. Eighty times more powerful than carbon dioxide over a 20-year timespan, methane emissions are estimated to be responsible for 30% of human-induced global warming to date. The oil and gas industry, which produces 41% of Canada’s methane emissions, is the leading source of anthropogenic methane emissions in the country1.

Canada can point to some success. Methane emissions from oil and gas have fallen by a third in a decade led by strong federal and provincial policies and industry practices.2 Canada committed to reducing its methane emissions from oil and gas by 40 to 45% over the 2012–2025 period, long before it signed the Global Methane Pledge at COP26 in 2021—and is already close to its set target. But the country will need to go further and faster, with an updated federal commitment to reducing its 2012 emissions by 75% by 2030. It’s a tall order. New federal methane rules announced at COP28 in Dubai could serve as a catalyst for climate action on stamping out the greenhouse gas.

Pushing Production, Pulling Emissions

Growing hydrocarbon production over the rest of the decade could lead to greater methane emissions and hobble Canada’s chance of meeting those targets without adequate additional abatement measures. One example: liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports will grow significantly once the first LNG Canada exports set sail by mid-decade. More housing will also mean more natural gas—at least for the foreseeable future3. Moreover, the Trans Mountain oil pipeline expansion will add nearly 600,000 barrels per day of new export capacity and could add to the industry’s emissions count if growing production fills this capacity over the rest of the decade. (See “Canada’s Energy Transformation” in the next section.)

Against this backdrop, Canada’s oil and gas sector finds itself in a tough spot. By 2030, the industry must cut emissions by at least 43%, remain competitive, continue to fuel economic growth, and provide energy security for Canada and its allies.

Canada Must Accelerate Methane Abatement

Methane emissions, Mt CO2e

Source: National Inventory Report, RBC Climate Action Institute analysis

An LNG Issue

While the oilsands usually gets much of the emissions spotlight, it’s Canada’s conventional oil and natural gas sources—such as the Montney basin straddling Alberta and B.C. and the Bakken Formation in Saskatchewan—that have the biggest methane challenge. About 80% of methane emissions come from these resources compared to just 8% from the oilsands.4 Canada’s expanding conventional oil and imminent natural gas production increases put these targets at risk. B.C.’s LNG ambitions alone could drive up natural gas supply by 25% and grow exports to 3.6 billion cubic feet per day over the rest of the decade.5

The industry will need to reduce its methane emissions by 21 million metric tonne carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e by 2030, increasing its historic rate of methane abatement by 25%.6 That requires more stringent rules and investing in technologies to stem “fugitive” methane leaks from the thousands of wells, gathering pipes, compressors, natural gas pipelines, and distribution facilities that span Western Canada. It would also mean stamping out methane venting, where the gas is released into the atmosphere, sometimes to release pressure or discarded as waste. (Oil production facilities that can’t flare—or intentionally combust the gas—usually treat it as waste in favour of more economically valuable oil.)

Conventional Oil and Gas Dominate Methane Emissions

Mt CO2e

Source: National Inventory Report, RBC Climate Action Institute

New, Stricter Methane Rules

Methane is a marketable product that’s bought by utilities and industries to heat homes and fuel manufacturing processes. That makes it a rare breed among greenhouse gases: unlike carbon dioxide, capturing and selling methane into natural gas markets can be a lucrative revenue stream.

Regulations will need to step in where natural gas prices don’t justify abatement costs. The federal government’s recently amended methane regulations could emerge as a catalyst. The regulations, expected to be published in late 2024, could drive emissions reductions from fugitive sources, and could push industry to either conserve vented methane or combust it to CO2 (reducing its global warming potency). In addition, high-risk facilities will be subject to additional inspections. If rolled out, the rules will overhaul Canada’s oil and gas industry, driving the installation of thousands of new methane compressors, combustion systems, electric pumps, and other kinds of hardware to rein emissions in.

The prize could be substantial methane abatement on its own could take Canada a long way towards its oil and gas emissions goals at a price point that is lower than many other kinds of climate action. Compared to CCUS, with its high capital expenses and operating costs and long timelines to plan, permit, and build projects, methane abatement comes without breaking the bank. As much as 217 million tonnes of methane and associated emissions can be abated between 2027 and 20407 by investing $15 billion in proven technologies like compressors, according to federal estimates.8 At $1.3 billion annually, or about $71 a tonne CO2e, methane abatement is less expensive than decarbonization measures in many other sectors and competitive with escalating carbon prices. In short, methane abatement could be one of Canada’s most powerful climate action levers9.

Methane Emissions Intensities Are Falling

Left Axis: emissions intensity (ktCO2e/mmbbl); Right Axis: production (mmbbl/d)

Source: Canada Energy Regulator; RBC Climate Action Institute

Canada Needs Better Methane Measurement

Counts of abatement projects from Canada's largest methane emitters

Source: Canada greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, IEA, RBC Climate Action Institute

Credible Methane Counters

As Canada gears up to combat methane, a major concern is the possible undercounting of emissions. Only seven out of 130 methane abatement projects from Canada’s leading methane emitters focused on monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV), emphasizing that more focus is needed on this critical area.10 Canada channelled $30 million into a newly announced methane centre of excellence unveiled at COP28 to help advance methane monitoring and measurement science and narrow down estimates. But these are early efforts, and further action including additional financing will be needed to bring Canada’s methane numbers down.

Related Reading

Canada’s Energy Outlook

To map out the expected trajectory for both energy supply and demand in the 2030s, RBC Economics & Thought Leadership and RBC Capital Markets recently published a report, Canada’s Energy Transformation: An Outlook of Supply and Demand in the 2030s(opens new window), which used global and national datasets, and new projections to outline where market trends could go in the coming decade.

Here are some key findings:

- The world will need to supply another U.S. worth of demand. Middle income countries such as Brazil, Mexico and South Africa are home to 75% of the global population and 62% of the world’s poor. Their rising disposable income, and aspirations to buy motorbikes, homes and electronics will require all forms of energy.

- Renewables will account for 20% of global energy needs. Between 2010 and 2020, the cost of solar and wind power fell 56% and 85%, respectively. However, political calculations could change the trajectory of renewable adoption in many counties.

- Peak oil demand is coming—but not yet. We assume global oil demand will continue to slow as a share of total energy consumption, but volumes consumed will not outright peak before 2035.

- Natural gas faces a more uneven transition. Globally, natural gas demand growth is expected to be driven primarily by increased demand in emerging markets—enough to ensure total demand for natural gas is not likely to peak until after 2035. The pace of growth will average about half the 1.8% annual rate over the last decade, and the share of natural gas in the total global energy mix will edge lower with renewable power sources growing more quickly.

- Oil investments: capturing value, capping emissions. Decarbonization strategies may present the most significant capital need for Canadian oil and gas producers heading into the 2030s. Plans and proposals for decarbonization projects including carbon capture and sequestration, will require tens of billions of dollars of new capital. That would be critical as we expect Canadian oil production to rise by 16.5% by 2030.

- Canada’s population growth will require a broad energy mix. Canada’s share of renewable power is still relatively high (25%) compared to other countries, mainly due to the availability of abundant hydropower. But the impressive figure masks a weakness. Canada is one of the few advanced economies that failed to increase that share significantly over the past decade.

Important Notice Regarding Information on this Website and Caution Regarding Forward-Looking Statements

The information on the Climate Action Institute website is intended as general information only and does not constitute an offer or a solicitation to buy or sell any security, product or service in any jurisdiction; nor is it intended to provide investment, financial, legal, accounting, tax or other advice, and such information should not to be relied or acted upon for providing such advice. Nothing herein shall form the basis of or be relied upon in connection with any contract, commitment, or investment decision whatsoever. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained herein, and neither Royal Bank of Canada and its subsidiaries (“RBC,” “we,” “us,” or “our”) nor any of RBC’s affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damage arising from the use of any information contained herein by the reader.

From time to time, we make written or oral forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, including on this website, in filings with Canadian securities regulators or the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and in other communications. Forward-looking statements on our websites include, but are not limited to, statements relating to our economic, environmental (including climate), social and governance-related objectives, vision, commitments, goals and targets as well as potential events and actions. By their very nature, forward-looking statements require us to make assumptions and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties, which give rise to the possibility that our predictions, expectations or conclusions will not prove to be accurate, that our assumptions may not be correct, and that our objectives, vision, commitments, goals and targets will not be achieved. We caution readers not to place undue reliance on these statements as a number of risk factors – many of which are beyond our control and the effects of which can be difficult to predict – could cause our actual results to differ materially from the expectations expressed in such forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest Climate Report, available at our ESG Reporting site.

Except as required by law, none of RBC or any of its affiliates undertake to update any information on this website.

All expressions of opinion on this website reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. We do not guarantee the accuracy of the information or expressions of opinion presented herein and they should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by RBC or any of its affiliates.

All references to websites are for your information only. The content of any websites referred to on this website, including via website link, and any other websites they refer to are not incorporated by reference in, and do not form part of, this website. This website is also not intended to make representations as to ESG-related initiatives of any third parties, whether named herein or otherwise, which may involve information and events that are beyond our control.