Key Points

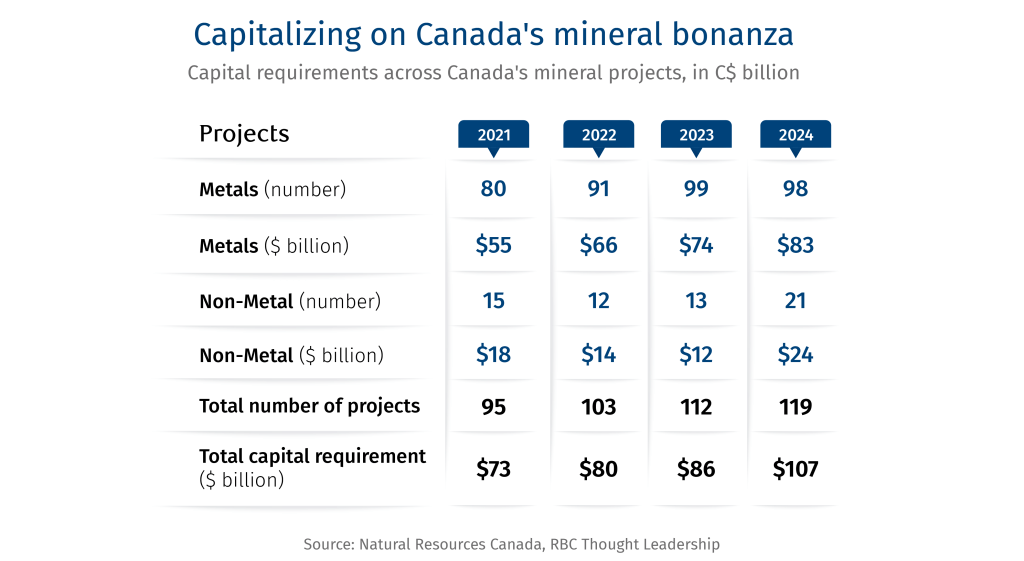

More than 100 mineral projects, valued at $107 billion, are at various stages of development in Canada over the next ten years. Unlocking that potential requires diversified capital flow, both domestic and foreign, for Canada to emerge as a commodity powerhouse.

With Chinese capital constrained by stricter federal rules, American capital is the natural partner to help develop Canada’s mineral resources, given the two countries’ geo-strategic alignment. Still, recent bilateral trade tensions with the U.S., suggest Canada should be clear-eyed entering into new partnerships and diversify capital sources to derisk projects.

If part of a broader security framework, Canada can position itself as a key pillar of the U.S.’s focus on breaking China’s hold on the supply chains of several commodities critical for defence, energy and high-end manufacturing. New cross-border commodity supply chains could serve as the bedrock of a North American high-end manufacturing, defence and energy infrastructure revival.

Building metal and critical mineral projects requires patient, long-term investors who can guarantee either long-term offtake agreements or security of demand to ensure their economic feasibility. To derisk projects, Canada could broaden its capital base beyond the U.S. and tap various global sources of foreign capital that are on the hunt for strategic assets—provided they meet Canada’s national interest and energy security thresholds.

Canada in the Great Resource Game

Canada’s vast natural resources present compelling investment opportunities. Crucially, they’re becoming strategic assets for G7 and other allies in a fragmented world.

Mineral development also gives Canada an opening to service several core verticals—automotive, energy equipment, defence, and high-end manufacturing. With the right strategy, Canada can position itself as a new manufacturing supply chain hub in a geopolitically-charged world, as we wrote in The New Great Game.

But injecting geopolitics into the minerals development space is a double-edged sword.

This was evident in recent years with China, a major supplier of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the global mining sector. Its involvement in Canadian minerals over the past few years have come under strict scrutiny on security concerns—coming to a head in 2022 when Ottawa ordered three Chinese entities to divest from three Canadian mining companies. The move has largely frozen Chinese interest in Canada’s minerals’ sector.

American companies are seen as more natural partners for Canada to develop mineral resources, given the countries’ long-standing geopolitical alignment. Despite the U.S. trying to squeeze Canada on trade, defence and several sectors such as lumber, automotives and steel and aluminum, the synergies on metals and minerals could be strategic for both countries. Recent U.S. rhetoric aside, there is a sense that collaboration on several metals and minerals supply chains would fortify North American energy and national security.

Trump charts a new direction

Washington’s approach to minerals development is still being laid out.

Signals indicate that the U.S. is poised to act decisively on critical minerals1 and other resources it considers vital for defence, technology, and semiconductors. The White House has fast-tracked 10 mining projects, signed an executive order aimed at stepping up deep-sea mining within U.S. and international waters, and floated the prospect of investing directly in mining companies, including through a proposed U.S. sovereign wealth fund.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s hawkish stance on resource-rich Greenland, the recent signing of a minerals deal with Ukraine, and interest in one with the Democratic Republic of Congo, suggests minerals are a strategic asset in the U.S. quest to counter Chinese dominance.

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s interest in connecting trade talks with U.S. national security, dovetails with American interest in energy and minerals development. As recently as December2, the two countries had invested in a critical mineral project in Yukon, part of a broader bilateral collaboration under the Canada-U.S. Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration and the Canada-U.S. Energy Transformation Task Force.

The U.S. and Canadian governments have already injected billions in capital into the space. Between 2021-2024, the U.S. government funded at least 24 critical minerals and materials projects, including five in Canada jointly with the Canadian government. Ottawa has also funded at least another five projects as of early 2024.

While Canada is keen to partner with its American counterparts on mineral development, it has taken measures in recent months to place some guardrails over its assets in a world that’s become more transactional and unpredictable. In March 20253, the Innovation, Science and Industry Ministry, responsible for Canada’s investment review, expanded the criteria for national security review to include economic security, in a move seen directed at the U.S. And in April 2025, the Government of Ontario introduced new measures “to prevent foreign governments or corporations from claiming Ontario’s critical minerals.”4

Securing geo-strategic capital

To further derisk its resource base, Canada should tap into a wide variety of capital that’s on the hunt for strategic assets.

The Canadian mining sector is already a major capital magnet. There are currently more than 100 mineral and mining major projects underway in Canada at various stages of development (announced, in review, approved or under construction) valued at more than $107 billion in capital, according to the Natural Resources Canada’s major projects database. And the list has ballooned in recent years as interest in Canadian resources has grown.

But where will the capital come from?

As miners gear up for future development, they could tap four sources of capital: self-financing, global equity markets, foreign state-owned entities, and sovereign wealth funds (SWF)— each aligned to different investment horizons and risk appetites.

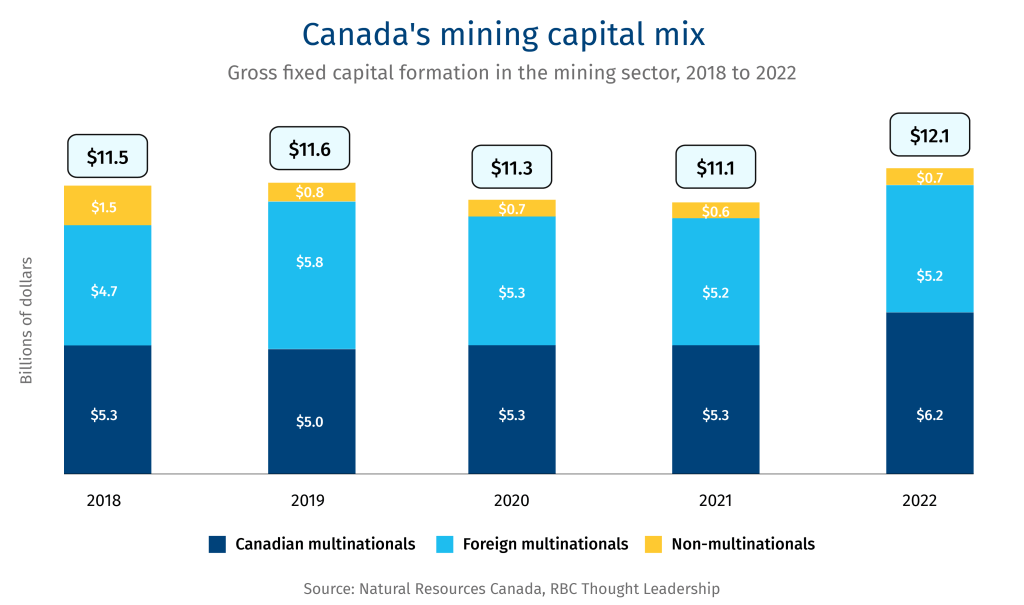

Foreign capital is already a well-established feature of Canadian mining, making up around 40-45% of investments flowing into the sector over the past few years.

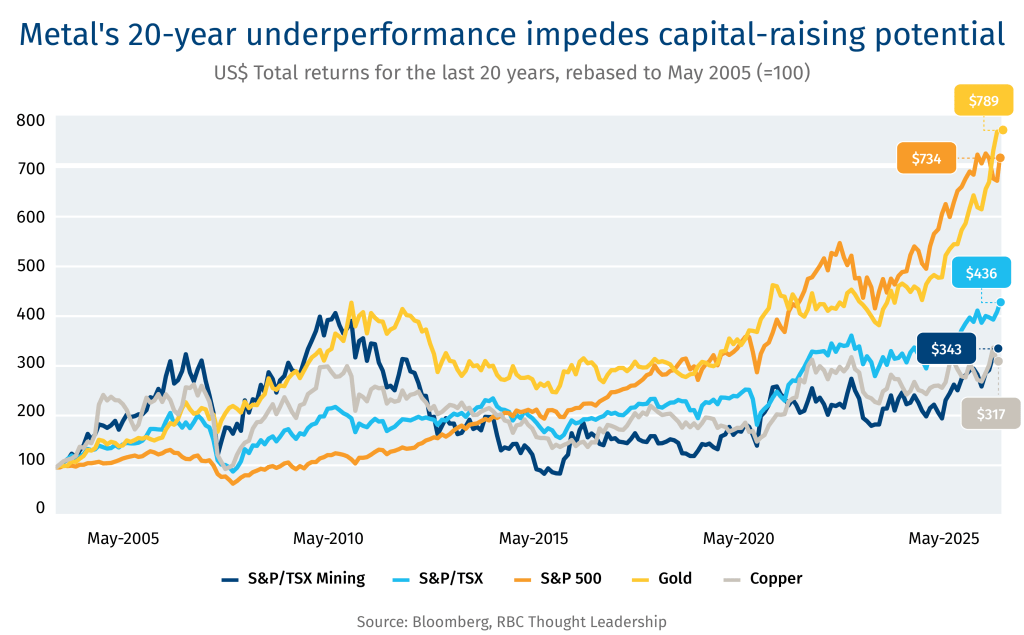

Self-financing: Over the past two decades, capital raising for the minerals sector has been challenged as mining and mineral companies have lagged both the underlying commodity and the broader index. Across equities specifically, this underperformance is even greater on a risk-adjusted basis given the lower volatility in returns for both the S&P/TSX Composite and the S&P 500.

This has emerged as a key financing challenge for companies. Yet a new commodity super cycle, driven by geopolitical and energy transition dynamics, could drive renewed investor interest in the sector.

Despite the market underperformance, Canadian miners are generally in good shape to partially fund projects. The sector enjoys financial strength and discipline as evident from its 0.7x capex-to-cash-flow over the past 12 months (compared to 1x in the past 10 years), indicating that funds are available to invest, while the debt burden has also fallen considerably in recent years5.

All told, the S&P/TSX metals and mining firms have accumulated as much $14 billion in excess cash flow over the past 12 months, ready to be deployed globally6. While Canada could attract a portion of that, companies will still need to tap into a variety of other capital sources to finance projects.

Equity markets: Public equity markets remain a viable capital source. New corporate equity issuance is also an attractive option from institutional and Western capital, majority of which is composed of passive or long-only funds. While investor risk appetite has been lukewarm, new macroeconomic and geopolitical drivers, coupled with strong company balance sheets could shift investor sentiment.

State and SWFs: Sustaining some of these projects with long gestation periods require geopolitical actors that take a long-term view on strategic resources. They are already on the hunt: between 2022-2024, we estimate that about 20% of global mining M&A originated from sovereign wealth funds (SWFs). The share of state-linked transactions was almost certainly higher, since the majority of China’s 18% share of global deals would have been done through its state-linked corporates.

State capitalism extends beyond sovereign wealth funds, and could include corporations that are linked to or championed by governments.

Among such state-owned entities, not all actors would be classified as high geopolitical risk like those from China, in terms of threatening market control or transferring minerals’ intellectual property (IP). Clean energy infrastructure funds linked to public pensions funds, sovereign wealth funds or large private equity firms are also eyeing opportunities in mining. Canada’s well-capitalized pension funds could also play a role here.

Other deep-pocketed investors—such as Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds and state-owned entities—could be more active in the future. While an important source of capital, they could pose security challenges, ranging from shifting geopolitical alliances or bilateral diplomatic spats, such as Canada’s diplomatic fight with Riyadh in 2018 over Saudi Arabia human rights record.

Containing China

The issues around security of strategic assets cannot be underestimated, and will only gain more traction, as evident with Washington and Beijing locking horns over supply chains. As President Trump embarks on signing trade deals with several countries, he may pressure those nations to purge Chinese capital from their mining supply chains.

That wouldn’t be entirely without precedent. Concerns over Chinese capital compelled the prior U.S. administration of Joe Biden to enhance its internal review of new Chinese investments in critical minerals and other strategic sectors7. In the past, Washington has also raised concerns more broadly about new Chinese investment in its allies, putting pressure on close trading partners Canada and Mexico to fortify their review processes.

Bolstering the Investment Canada Act

That has already triggered a shift in how Canada has handled Chinese investments in recent years. In 2022, the Investment Canada Act (ICA) national security provisions were enforced to require the divestiture of Chinese investment in three Canadian critical minerals companies with lithium mining activities. In doing so, the critical minerals sector was flagged for enhanced government scrutiny8.

Further amendments over the past year give the federal government enhanced scope to complete a national security review for any new foreign investment in Canada, not just those with controlling interests, and greater scrutiny of investments by state-owned entities (SOE), which primarily targets China.

Amendments also asserted quasi-extraterritorial powers of the ICA – that the foreign assets of Canadian businesses were within scope of ICA review in case of foreign SOE acquisition.

Canada’s expanded reach

Combined with the fact that Canada has major mining concentration—the Toronto Stock Exchange and the TSX Venture Exchange represent 40% of the world’s public mining companies and are home to more than a 1,000 listings—, the ICA’s quasi-territorial means it’s a powerful tool for policing some Chinese investments abroad. Canada has recently asserted this authority, with two Canadian companies attempting to re-domicile to avoid the ICA review.

In the case of a more significant break with China, President Trump may seek a broader Chinese investment purge by Canada as the cost of participating in U.S.-centric supply chains. For one, it could push Canada to test its powers under the ICA. It could also take issue with some legacy investments by Chinese state-owned companies in large Canadian miners (see Managing legacy Chinese investments).

However, a provoked China could retaliate against Canada by closing its markets to certain exports, similar to its tariffs on Canadian canola in March, or by further weaponizing its supply chain.

Even as China’s capital or long-term supply agreements may no longer be welcome in the Canadian mining sector, it remains a major supplier of industrial equipment and parts. Western governments could replace Chinese equipment over time, but it is sand in the gears of further developing resources. Trump’s recent backtracking on Chinese tariffs at the behest of American corporations points to the importance of Chinese materials in the global economy.

Managing legacy Chinese investments

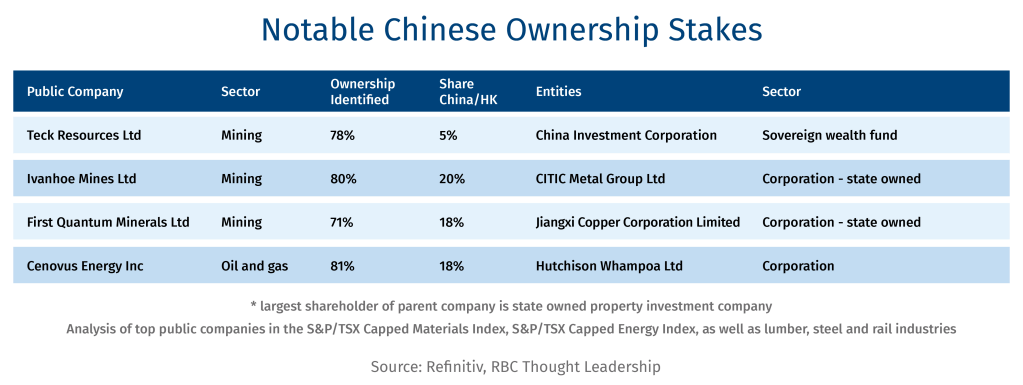

Analyzing the largest public Canadian mining companies reveals three with material Chinese ownership from state-owned entities. No major U.S. mining companies have similarly significant or state-sponsored Chinese interests.

Given that these are legacy investments, the Canadian government lacks the legal authority to compel their divestiture, notwithstanding the shifting national security lens.

In the U.S., President Trump’s recent political pressure may have compelled the planned sale of Hong Kong-based Hutchison Whampoa’s stake in Panama Canal and other ports to an American-led consortium (currently paused while under review by China). Ergo, other tools may be within the Canadian government’s control to achieve its aims, but they could come at the cost of provoking China and damage to Canada’s reputation as an investor-friendly jurisdiction.

Canada’s investment opportunity

The world’s looking at Canada as a stable and dependable commodity player to help diversify its commodity supply. It’s also a generational opportunity for the provinces and the federal government to unlock resource developments that are rich in gold (vital as a safe haven commodity), copper, iron and critical minerals. The right strategy, investments and security measures can help power Canadian mining.

Contributors:

Cynthia Leach, Assistant Chief Economist, RBC Economics

Shaz Merwat, Energy Lead, RBC Thought Leadership

Vivan Sorab, Senior Manager, RBC Thought Leadership

Yadullah Hussain, Managing Editor, RBC Thought Leadership

Caprice Biasoni, Graphic Design Specialist

Shiplu Talukder, Digital Publishing Specialist

[1] https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/unleashing-americas-offshore-critical-minerals-and-resources/

[2] https://www.canada.ca/en/natural-resources-canada/news/2024/12/canada-and-united-states-co-invest-to-unlock-critical-minerals-development-in-yukon.html

[3] Guidelines on the National Security Review of Investments – Investment Canada Act

[4] Protecting Ontario’s Critical Minerals and Energy Sector | Ontario Newsroom

[5] The sector’s capex-to-cash flow of 0.7x over the past 12 months and debt-to-cash flow ratio of 1.1x are both well below their 10-year averages of 1.0x and 2.1x, respectively.

[6] Float-cap weighted average trailing twelve month operating cash flow less capital expenditures less dividends less buybacks across the S&P/TSX Metals and Mining Index (GICS Level 3)

[7] https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/09/20/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-takes-further-action-to-strengthen-and-secure-critical-mineral-supply-chains/

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.