The enactment of the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA) in July 2025 represented a watershed moment in American fiscal policy, but its impact won’t be felt evenly across the population.

The legislation (now known as Public Law 119-21) builds on and makes permanent prior provisions from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), and represents $5 trillion in tax provisions over 10 years. The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects it will add a 0.9 percentage point to real GDP in 2026 and as the legislation takes full effect.

But we anticipate a distinct “barbell” effect. On one end, capital intensive corporations and upper-middle class households in high-tax jurisdictions will see tax burdens reduced through permanent rate extensions, depreciation adjustments, and expansion of the State and Local Tax (SALT) deduction cap.

On the other end, lower-wage workers in leisure and hospitality and hourly sectors (e.g., manufacturing) will receive targeted relief through novel deductions for tip and overtime income. However, the middle of the distribution, and particularly, non-working, low-income households reliant on government transfers will face a severe contraction of support.

The structural overhaul of Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), driven by rigid federal work requirements and new state cost-sharing mandates, creates a fiscal environment where access to a safety net is no longer a guarantee based on need.

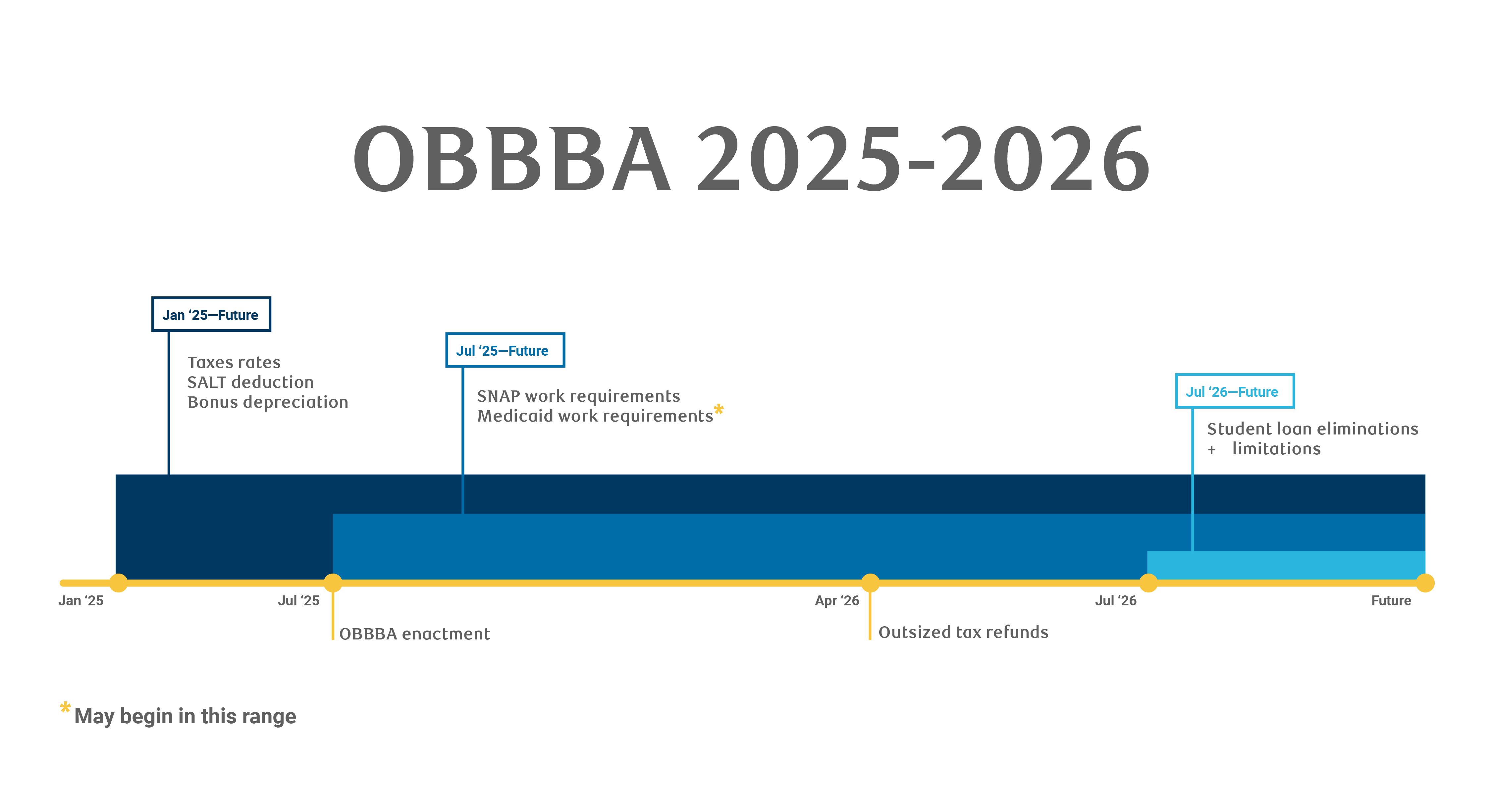

Timeline: What hits and when

The legislation has a cascading implementation schedule that distributes impact unevenly across four quarters of 2026. As a result, we think consumer sentiment, household liquidity, and purchasing power may fluctuate between the first and second halves of the year.

We breakdown what is included in the legislation based on timing of implementation and scope of impact on US growth.

Changes with immediate impact

Capex and depreciation changes

The OBBBA enabled 100% bonus depreciation for qualifying capital investments and reinstated immediate expensing of research and development costs. Restoring the 100% depreciation is a large win for capital-intensive industries. Under the TCJA, bonus depreciation was scheduled for gradual phase-out following 2023; under the OBBBA, it was restored to 100% retroactively for assets acquired mid-January ’25 onwards. The after-tax costs of new machinery, fleets, and equipment can be seen to have fallen by around 21%. These moves were designed to encourage immediate capital outlays by allowing businesses to write off these types of expenses in the year they are incurred rather than amortizing them over five years, significantly reducing the near-term tax burden for capital intensive industries.

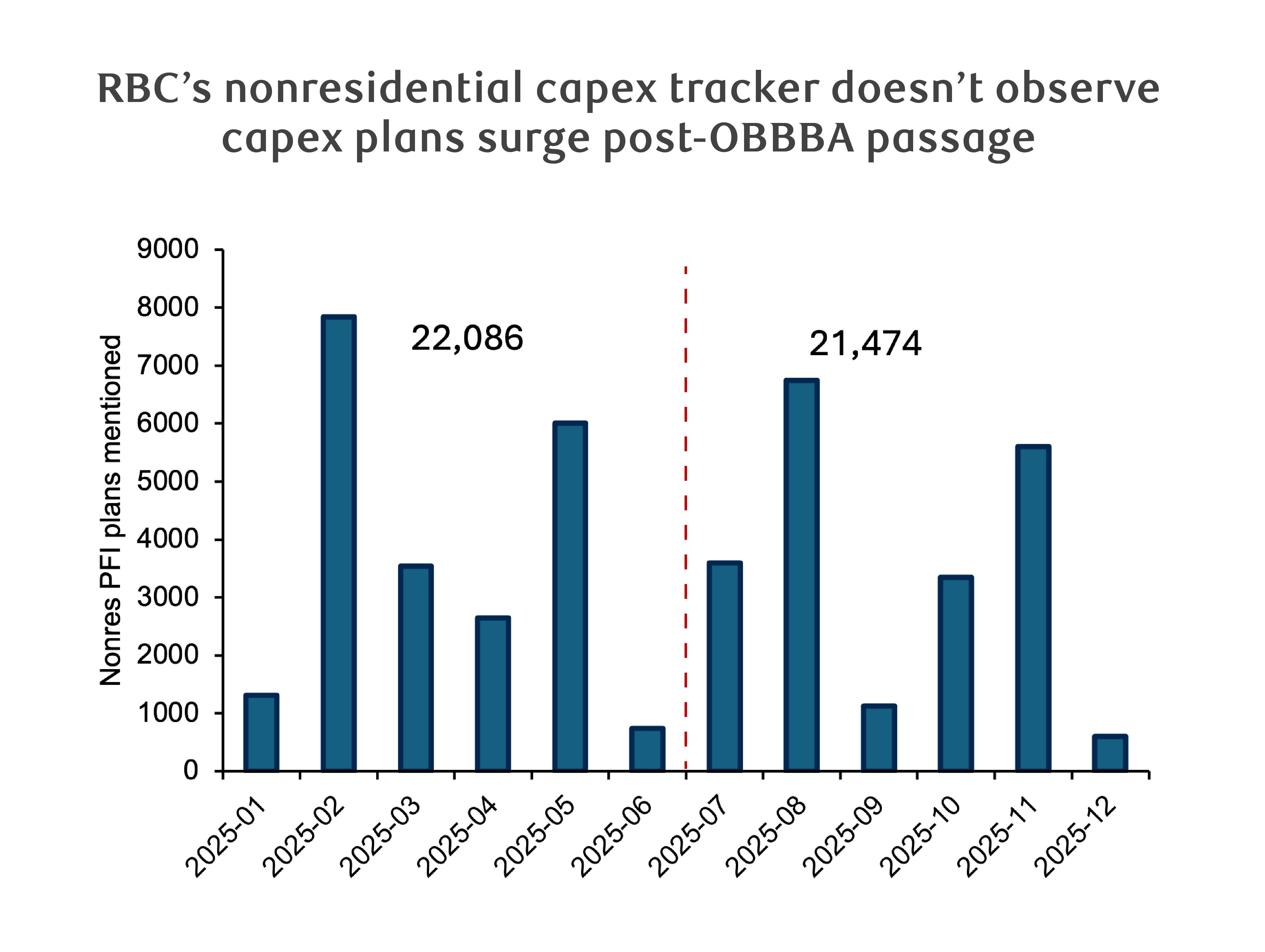

It would not be appropriate to attribute the entirety of planned capex in 2026 to this legislation. In fact, there were known capex plans in place prior to OBBBA’s passage.

Our nonresidential capex tracker observes just over 22k nonresidential capex projects announced prior to July 4, 2025, by publicly traded companies. Similarly, capex plans announced post-OBBBA amounted to just over 21k projects. In that lens, we can not necessarily attribute the entirety of capex plans to the legislation, but rather some portion.

Put another way, in an alternate world without bonus depreciation, we would still expect to see companies commit to some amount of capex. In that lens, the marginal impact of bonus depreciation is difficult to measure, but we do think it’s consequential.

SNAP adjustments

Certain adjustments are made to the administration of nutrition assistance.

The Thrifty Food Plan is to be adjusted annually to reflect changes in the CPI, requirements for the states to match certain SNAP costs in accordance with their respective payment error rates, ending funding for SNAP Nutrition Education and Obesity Prevention grants, and revisions to limit SNAP to US citizens and lawful residents (functionally excluding refugees and asylum seekers).

Like adjustments made to Medicaid, modifications to SNAP also include work requirements for able-bodied adults of working age. This includes limitations on cost reevaluations, reductions on utility allowances, and adjustments to income eligibility among others.

These provisions are estimated to reduce direct spending by nearly $106 billion and SNAP participation by 2.4 million people (in an average month) between 2025 and 2034.

SALT deduction cap adjustments

The TCJA had set the individual deduction limit of state and local taxes at $10,000. The OBBBA increases this cap to $40,000 and makes it effective for tax years 2025 through 2029. Income limits gradually reduce this benefit beginning at $500,000 of annual income.

Taxpayers with incomes above $600,000 can only deduct the original $10,000. Still, the change will be most impactful in the 2026 calendar year when households receive tax refunds for 2025 (i.e., due to the retroactivity).

We expect this will be most pronounced in high-income, high-cost-of-living states along the coasts.

Tax withholding adjustments

The federal income tax cuts for tips and overtime pay were technically retroactive to January 1, 2025, but the IRS and payroll processors required time in 2025 to update reporting systems.

Consequently, employers are now legally required to adjust tax withholding tables and reporting requirements to reflect these exemptions as January 1, 2026. For all of 2025, workers had taxes withheld on income that was technically tax-privileged, creating a “forced savings” situation—as workers will receive tax refunds when filing 2025 tax returns this year.

Starting January 2026, employee paychecks must explicitly reflect the exemption, resulting in an immediate, albeit modest, bump in take-home pay for these workers. The provision of this legislation that allows deductions applies only to the premium portion of the pay (“half” of the time and a half), not the base pay for these hours.

What is coming into effect in 2026

Income tax rate changes

The OBBBA locks in individual income tax brackets created by the TCJA set to expire in 2025.

It codifies the seven-bracket structure and the greater TCJA standard deduction amounts along with a longer list of eligible deductions and refunds outlined below.

Tax season liquidity injection

The period from February through April 2026 represents the moment of maximum liquidity injection for the household sector, creating a potential peak for consumption in Q2.

This tax filing season is unique as it combines the standard refund cycle with the retroactive “true-up” of the tip and overtime tax exemptions for the 2025 tax year.

Since withholding tables were not adjusted in 2025, service workers and hourly employees, who worked substantial overtime effectively overpaid federal income taxes throughout the previous year. Again, the OBBBA allows these taxpayers to claim a deduction for “qualified tips” (up to $25,000) and “qualified overtime” (up to $12,500 for singles, $25,000 for joint filers) on 2025 tax returns filed in early 2026. Hence, tax cuts are in some cases converted into a lump-sum payment.

Economically, regular pay bumps (larger checks) are often absorbed into daily consumption, but lump sums may still be used for big ticket purchases (electronics, vehicles, appliances), debt reduction, or savings. In light of recent consumer delinquency data, we expect debt reduction will be prioritized over consumption—a key factor in our slower growth profile for 2026.

Average tax refunds in tax years 2023 and 2024 were $3,004 and $3,054, respectively. Estimates vary, however, and various estimates place tax year 2025’s refunds nearly $100 billion higher than the previous year with average refunds being increased between $300 to $1,000 compared to the prior two years.

Recent dips to personal savings rates have been observed relative to 2022 and 2024. Compared to this period, personal savings in Q2 2025 , on an annualized basis, were at an $732 billion shortfall, while Q3’s modest moderation brought it nearly $191 billion lower. Refund sizes depend on taxpayers’ circumstances, but overall, we estimate major tax changes for 2025 will lead to a notable increase in after-tax income (i.e., disposable income), supporting personal savings rates of middle and upper-middle income groups.

Child Tax Credits

The act increases the maximum credit from $2,000 to $2,200 per qualifying child, also effective for the 2025 tax year. It introduces a permanent inflation adjustment as well for this tax credit starting in 2026. This credit is partially refundable (cap is $1,700).

Student loan changes

Effective July 1, 2026, the OBBBA will eliminate the existing set of income-driven repayment plans for new borrowers, including the more generous SAVE plan, Pay as You Earn (PAYE), and the Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR).

The situation is more complex for existing borrowers. More critically for consumption, this date marks the beginning of strict borrowing caps. The Graduate PLUS loan program, which previously allowed unlimited borrowing up to the cost of attendance, is eliminated entirely for new borrowers. It is replaced by unsubsidized loan caps of $20,500 for most graduate degrees and $50,000 for professional degrees (law, med) with lifetime limits of $100,000 and $200,000, respectively.

Simultaneously, Parent PLUS loans—the financial backing of many private universities—will be capped at a lifetime limit of $65,000 per student.

This hits immediately for the Fall 2026 semester. Families who had planned to finance tuition in August 2026 using federal loans will find the window closed. They will be forced into the private student loan market, where interest rates are significantly higher than federal rates.

This shift represents a structural tightening of credit that will siphon liquidity from upper-middle-class households (who use PLUS loans) and bring difficult choices about enrollment likely impacting consumption as families divert funds to tuition.

Medicaid work requirements

Medicaid work requirements will be introduced in some “early adopter” states in 2026 (with Georgia already introducing these requirements).

The federal mandate generally targets a 2027 implementation for full compliance, but the OBBBA permitted states to optionally adopt these measures early.

States primarily in the South and Midwest moved aggressively to implement these protocols (Montana, Utah, Arizona, Arkansas, Iowa, Ohio, and South Carolina all requested permission for early implementation, while Georgia has one in place since 2023).

In these jurisdictions, able-bodied adults aged 19-64 are now required to document 80 hours of work, community service, or job training per month to maintain eligibility.

Distributional impact

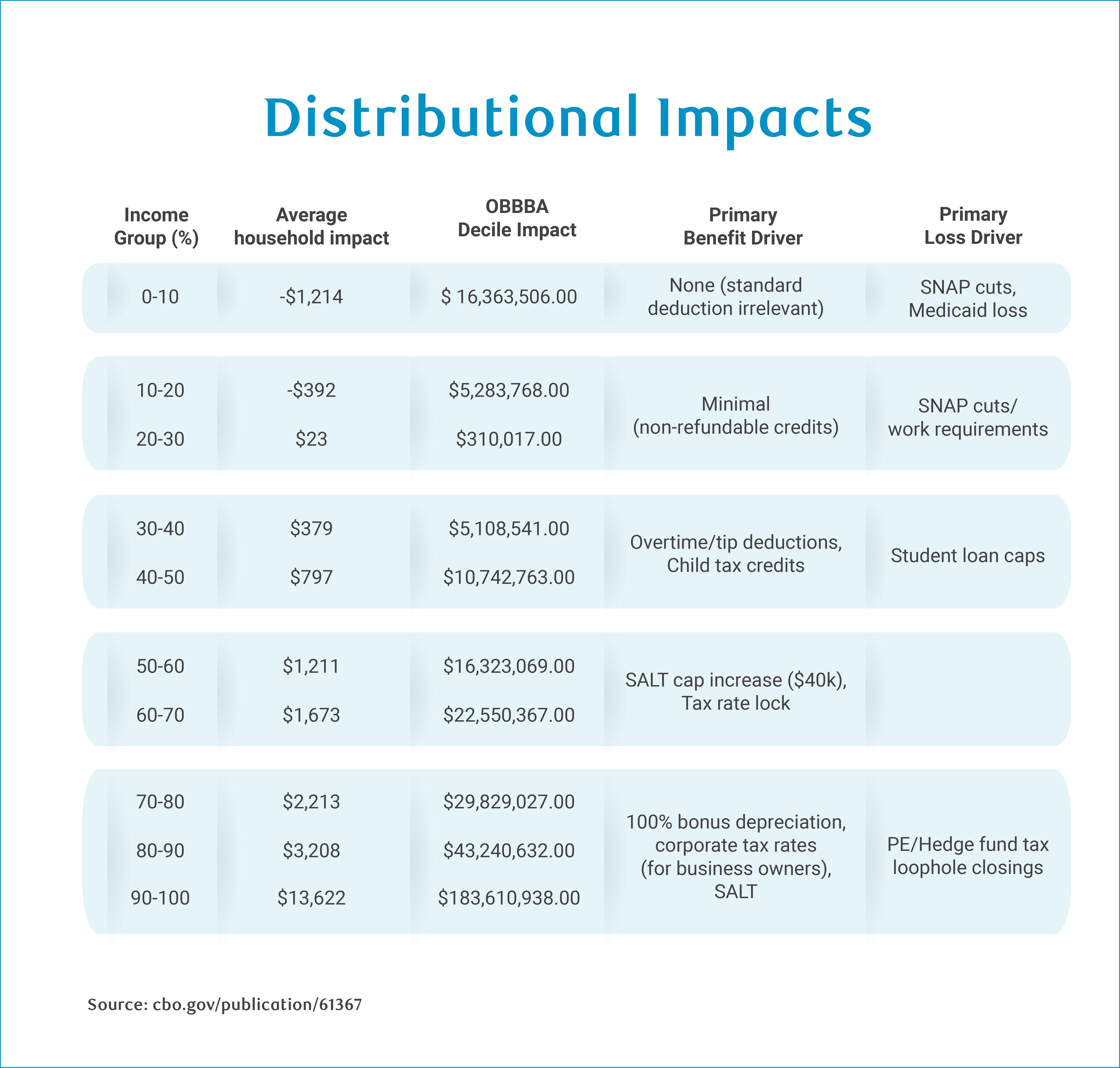

OBBBA has been marketed heavily on benefits for working-class service workers. Still, we see it as a legislation that skews to benefit top earners while the bottom quintile face losses on net from reduced transfer payments—in effect contributing to a growing K-shaped economy.

Lower income households will be worse off in the long run

The CBO estimates resources for households in the lowest decile will decrease by about 4% by 2033. The primary drivers are cuts to SNAP and Medicaid.

The OBBBA cuts SNAP funding by roughly $187 billion over a decade. The “No Tax on Tips” and “No Tax on Overtime” provisions are structured as deductions, not refundable credits (which would be more beneficial for low-income earners since credits can result in refunds).

Relevantly, a single taxpayer earning $15,000 in 2026 pays nothing in federal income tax due to the standard deduction of $16,100. Therefore, an additional deduction does not provide any benefit. The bottom 20%, in this case, lose transfer income (SNAP/Medicaid) and gain no tax relief.

High income households stand to benefit

Top earners, on the other hand, stand to benefit materially from changes to federal taxes and cash transfers.

Business owners and incorporated individuals will benefit from the 100% bonus depreciation, and all will benefit from locked-in income tax brackets. The CBO estimates the net effect of the OBBBA for the top decile will be a 2.7% increase in household income.

Many would assume this would result in a sizeable boost to household spending, especially as high earners and wealthy households have continuously propped up consumer spending.

However, since high income households have a lower marginal propensity to consume, they are more likely to save additional income rather than spend it. Therefore, the impact on household consumption is likely to be muted.

Low-income households, on the other hand, will spend each additional dollar in transfers they receive. Since low-income households tend to spend the bulk of take-home pay on essentials, we do not expect a pullback from the reduction in federal and state transfers. Instead, we expect to see a greater reliance on credit and Buy Now Pay Later programs.

About the authors:

Mike Reid is Head of U.S. Economics at RBC. He is responsible for generating RBC’s U.S. economic outlook, providing commentary on macro indicators, and producing written analysis around the economic backdrop.

Carrie Freestone is a Senior US Economist at RBC Capital Markets. Carrie is responsible for projecting key US indicators including GDP, employment, consumer spending and inflation for the US. She also contributes to commentary surrounding the US economic backdrop which she delivers to clients through publications, presentations, and the media.

Imri Haggin is an Economist at RBC Capital Markets, where he focuses on thematic research. His prior work has centered on consumer credit dynamics and treasury modeling, with an emphasis on leveraging data to understand behavior.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.