The World Economic Forum this year became a tale of two Davoses.

Inside the main Congress Centre, a record number of attendees, including 850 CEOs, 80 tech billionaires and founders, hundreds of ministers and 65 heads of government spent the week hearing about the decline of globalization and the inward turn of societies.

Outside, it was a very different world. On the town’s main promenade, you couldn’t walk 50 metres without feeling like you were in a mash-up of Wall Street, Silicon Valley and the United Nations, as countries from Brazil to Indonesia and companies from Tech Mahindra to Pinterest pitched themselves to the passing kaleidoscope of a crowd.

Mark Carney called this new environment one of “variable geometry.” Others called it a new age of “multi-alignment”—as if the global economy is becoming a bit more of a bartering and babbling souk than a tightly wired marketplace. By any name, the emerging world order, or disorder, seems as slippery and risky as the icy streets of Davos. Here’s some of what to look out for:

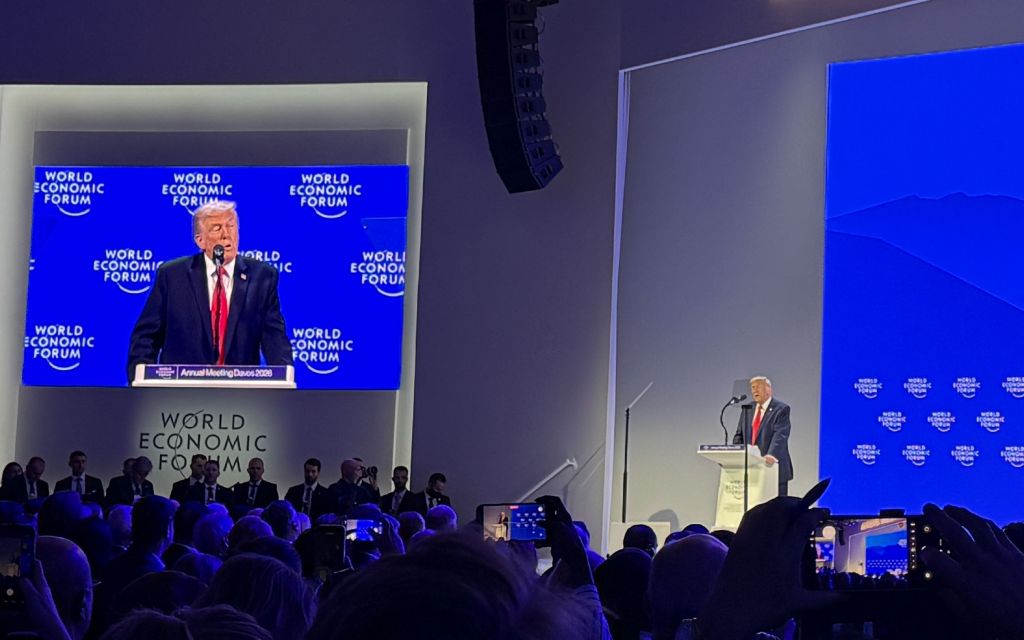

Trump’s World: America First or America Alone?

Last year, a day after his second inauguration, Donald Trump spoke by video to the Forum and promised a golden age for America. This time, he came in person to proclaim victory. With five cabinet secretaries and hundreds of American CEOs in tow, the President spent an extraordinary two days in the Swiss Alps projecting a 21st century version of American power. This is no stay-at-home superpower. In Trump’s vision, the world will trade and prosper more than ever, on America’s terms. Close to three-quarters of global trade is still compliant with WTO rules. Inventory build-ups helped many companies escape the initial tariffs. A greater impact may come this year. But for the most part, “it’s still holding,” said Christine Lagarde, head of the European Central Bank, arguing the global economy is so intricate and intertwined even the U.S. cannot unravel it. Trump’s more mercantile Pax America is not just economic. He came with an unsolicited bid for Greenland that was rejected by his closest NATO allies. He left with a Board of Peace, supported by an unlikely collection of 19 countries with a combined GDP of $5 trillion, roughly equal to Germany. Only four (Albania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Turkiye) are in NATO, and only four (Argentina, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Turkiye) are in the G20. Will Trump be able to expand America’s reach without stronger partners? Or is this the new geometry of power?

Carney’s World: Rupture or restoration?

Mark Carney, long viewed as the quintessential “Davos Man,” gave a keynote speech that was widely celebrated for capturing the distraught mood of many there and crystallizing the desire for a new approach to international affairs. His tag line—“nostalgia is not a strategy”—resonated. Now he has to deliver on diversification. There’s no easy path. Canada’s closest allies in Europe are each struggling, economically and politically, weakened by the Ukraine war, immigration crises and a growing appeal of nationalism, which is now the biggest political force on the continent. Europe’s biggest economy, Germany, narrowly escaped a recession last year, after two years of decline. Chancellor Friedrich Merz called Europe “world champions of over-regulation” and at risk of losing its unity if it doesn’t reform. Canada will need more distant partners, too, particularly China and India, which the WEF estimates will account for nearly 40% of global economic growth over the next five years. Both emerging giants can be as tough as Trump when it comes to trade. The Persian Gulf beckons, too, with trillions of dollars of capital investment. But there, too, a new generation of economic partners have different political and legal systems—and social customs—to the neighbourhood where Canada grew up.

“No King” comes for dollar

High above Davos, someone carved a message into a mountaintop glacier: “No King.” It was probably meant for the visiting U.S. President but equally could have been a message from European markets to the mighty greenback. King Dollar had a rough week, facing big questions as global trade winds shift, and countries and companies look to re-orient capital flows. The dollar still dominates 88% of global foreign exchange transactions, and 54% of global trade, which is why so many still cite TINA (There Is No Alternative). Or is there? The WEF opened to the startling news that Denmark’s largest pension funds had dumped U.S. treasuries in retaliation to the Greenland threat. A risk-off America vibe sent U.S. bond yields higher, reducing hopes for broader rate cuts. In moments like this, investors tended to stay in America, through real estate or stocks. This time, at least among Europeans, there was plenty of corridor chatter about a secular shift forming. One fund manager said his investors had asked him to sell down U.S. holdings. A few American tech executives said long-time European clients were cancelling orders. The euro, yen and Canadian dollar may play greater roles. The renminbi should gain prominence, although is years away from being a serious global alternative. Uneasy lies its head, but there’s still only one king wearing the currency crown.

Davos meets (and greets) state capitalism

The World Economic Forum was created in the 1970s to help Europe avoid the rise of socialism, and turn instead to free markets. A half century later, much of the West is again turning to the state to meet various economic ambitions—and the risks are evident. As countries, Canada included, seek to build back their militaries, build up their own technology foundations and become less reliant on the U.S.—home to roughly half the world’s financial capital—they are looking to leverage their own balance sheet and use other tools to direct capital to national priorities. These ambitions are so pronounced that many prime ministers and presidents seemed more like investment bankers working the Davos crowd. Advanced economies like Australia, Norway, Germany and South Korea do indeed have capacity to borrow more for investment, as do many emerging economic powers like Saudi Arabia. But capitalism is about more than capital; it’s about putting capital to work, with results. Singapore’s president, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, offered some sage advice, urging these new nation-state capitalists to be ruthless with investing, and with spending and regulation, too. Growth requires governments to focus on productive investments, including education, rather than redistribution—and a humble recognition that governments are inherently weak at building economic enterprises. If this new shot at state capitalism is to work, a new mindset will be needed, too.

Photo: World Economic Forum

Photo: World Economic Forum

Photo: World Economic Forum

Photo: World Economic Forum

Photo: World Economic Forum

Photo: World Economic Forum

Photo: World Economic Forum

Photo: World Economic Forum

China lies low, biding its time

Right after Donald Trump was first elected President, Xi Jinping came to Davos, to offer up China as a global leader for an emerging age. In the ensuing decade, Beijing has delivered—in renewable energy, nuclear power, critical minerals, pharmaceuticals and AI. So much so that Xi no longer needs to be there. This time, while the U.S. and Europe shouted at each other, he sent one of his less powerful vice premiers, He Lifeng, to position their country as a defender of multilateral trade and “inclusive globalization.” China experts said Beijing is not missing a moment to quietly advance its two biggest priorities—reunification with Taiwan and AI supremacy. Xi sees AI as critical to China’s future, and DeepSeek 4, the next-generation AI model expected in February, will show how far China’s come. On that other front, it’s believed the Chinese military, which conducted naval exercises around Taiwan at New Year’s, is ready to take the island by force, if necessary, within a year, which would give it sway over the world’s semiconductor industry that is so essential to AI. Democratic Senator Chris Coons, who was at Davos, fears the U.S. Administration doesn’t appreciate the need for “a network of allies with core values” to contain China. We’ll get a clearer picture when Trump and Xi meet in April, but don’t expect a grand bargain between the hegemons. Best case, Coons said, may be a series of “small landing points” to keep the world in balance.

Big Data: A new political target

Data centres seem to be eating the world, electron by electron. But will the capital be there again in 2026 to feed their financial appetite? Data centre spending surpassed $500 billion last year, and when combined with broader electricity needs, according to McKinsey, may total $6.7 trillion over the next five years. The world has never seen an infrastructure boom like this. Data centre construction is now the single biggest contributor to U.S. economic growth; tech spending as a share of all investment is now running 50% higher than it was during the broadband boom of 2000, and triple what the U.S. spent on Interstate highways in the 1960s. Vacancy rates for data centres recently hit a record low of 1.6%, as developers bid up available spaces. “We may need more,” said Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock. “If we don’t scale, China wins.” Equinix, a large data centre player, faces ten times the demand for every new unit they build. Land is no longer the constraint; energy is, as a medium-sized centre requires the energy of a small town. Such operations last year accounted for two-thirds of U.S. load growth, making them a new political target in boom states like Virginia and Ohio where electricity prices have soared. They’re also a growing concern in Africa and South-east Asia, the world’s fastest-growing regions, where countries have found themselves outbid for gas turbines and other power equipment.

AC or AI: It’s gridlock

The next energy crisis won’t be fueled by oil or gas; it will be strained by the world’s faltering electricity grids. Electricity demand globally is rising three times faster than total energy demand, driven by air conditioning and electric vehicles, as well as data centres. While 90% of Americans have access to air conditioning, the number is 20% in India, 18% in Indonesia and 5% in Nigeria—each with some of the world’s fastest-growing cities. Add to that the growing demand for EVs, which now account for a quarter of global car sales, up from 5% in just five years. Fatih Birol, head of the International Energy Agency, said the world will need 10,000 terra-watts of new electricity in the next decade, which is the equivalent of adding another U.S., Canada, Europe and Japan. Without any innovation breakthroughs, that would require 70% more copper, and a vast expansion of steel and critical minerals processing. Developments in large-scale battery storage and grid digitalization offer some hope, as most electricity systems still suffer a gross mismatch of supply and demand. But an unfortunate truth remains: it’s easier and faster to build power plants than it is to add transmission and distribution. Take this recent experience in Europe: the continent added 80 gigawatts of renewable energy supply only to find it didn’t have the capacity to transmit all that new electricity.

A renewable lease on energy

There were two vastly telling moments in Davos’s main Congress Hall, one speaking to scarcity, the other to abundance. Donald Trump went off script to lambaste renewable energy, especially wind which he said was for “losers.” A day later, Elon Musk used the same stage to profess a glorious future for renewables, especially solar which he said could power all of America if he had his way. Just give him a parcel of land, 160 kilometres by 160 kilometres, and tariff-free solar panels! Away from North America, renewables are still the driver of energy growth and have shifted from a “transition” source to a default for new supply in many markets. Europe reached roughly 50% renewable generation in 2024. In other fast-growing markets, renewables are increasingly seen as energy additions, not just replacements for fossil fuels. Falling battery costs (solar is down roughly 80% in India) and longer lifetimes (30–35 years) have helped shift economics from a simple cost per unit to a cost per lifecycle. But reliability remains a challenge, which will require more battery storage, pumped hydro, and hybrid round-the-clock systems. But that’s happening in places like India, which has installed 2.7 million rooftop solar systems and 3.1 million solarized pumps and has already hit its 2030 target for renewables to account for roughly 50% of non-fossil fuel energy.

For companies, AI goes small

AI has shifted from an experimental technology to foundational infrastructure—and now an operating system for companies and governments. The competitive advantage is not just model innovation; it’s diffusion and how fast firms can beat their competitors to transform. As diffusion accelerates, Anthropic co-founder and CEO Dario Amodei sees 2026 as the year when AI systems build AI systems, including within firms, in ways that could upend entire business models. Demis Hassabis, co-founder and CEO of DeepMind, said the advantage will go to “continuous learners” who track what models are doing and adjust strategies and workflows. Seizing that approach, most CEOs have taken AI ownership out of the tech department and parked it on their desk. A BCG survey, released at Davos, found that 72% of global CEOs see AI as a core part of their mandate, with half believing it will define their tenure. Companies plan to double AI spending this year, even though a 2025 MIT study found very few adopters had seen a financial return. David Sacks, the Silicon Valley guru who is Donald Trump’s AI czar, sees the need for leaders, in government, business and media, to dispel fears, and embrace the chance to disrupt and innovate. He cited another study that found 83% of Chinese are optimistic about AI, compared to 39% of Americans. Sacks worries that “a fit of pessimism” will result in the U.S. losing the AI race due to what he described as a “self-inflicted injury.”

On jobs, AI becomes snakes and ladders

There’s a new financial math for AI. It’s what Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella calls “tokens per dollar per watt”—basically the energy cost per unit of compute. Think of it as a kind of basic wage and productivity measure for AI. And the companies, and countries, that can drive down that unit cost will be positioned to win in the data economy. This new math may fundamentally change the nature of human work, too. Think of it as “data x energy x labour = success.” The C-suite consensus at Davos seemed to be that labour, like data and energy, will be needed even more. CEOs said the entry-level “job cliff” is overstated; the real problem is a widening skills mismatch, as most roles will require a re-bundling of tasks and skills. The winners will be the workers (and firms) that can integrate and operate with AI. This transformation is resetting corporate ladders, especially in professional services and governments, where basic tasks like document review, screening and modelling can be done by machines. New apprenticeship designs will be the hot HR need, to build judgement, context, and supervision skills. More model design and modification will be pushed to the frontlines, where employees can create small pieces of automation to transform their work. All this can flatten organizations, and give advantage to those with abundant data, cheap energy and AI-savvy teams.

Zero Sum = Zero Trust

Growing divisions in the world, and within countries, is a matter of trust. And we’re losing it. Stefanie Stantcheva, a Harvard economist, finds it’s especially acute for her generation—those under 40—who see a zero-sum world and their slice shrinking. She shared research at Davos showing how distrust now spans the political spectrum, with a wide range of millennials feeling other groups have captured government agendas through mainstream media, corporate influence and old-school politics. That tension will grow as aging voters in the West demand more income and health security, perhaps at the cost of economic and national security. The Edelman Trust Barometer, which surveys 34,000 people in 28 countries and is released annually at Davos, found societies sliding from grievance into insularity; seven in 10 people are hesitant or unwilling to trust those with different values, backgrounds, or information sources. Trust is also shifting away from institutions to “people like me,” neighbours, co-workers, and one’s CEO. Business is now seen as both most competent and most ethical, surpassing NGOs on ethics for the first time, while government and media remain the least trusted. Most starkly, optimism is fading: in many countries, majorities no longer believe they or their families will be better off in five years, citing economic anxiety, AI, misinformation, and global conflicts.

Download the Report

John Stackhouse is Senior Vice President, Office of the CEO, at RBC, and a senior fellow at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy at the University of Toronto. He is a former editor-in-chief of The Globe and Mail and was its correspondent in New Delhi from 1991 to 1999.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.