Recent trade tensions have amplified existing vulnerabilities in Canada’s labour market. After briefly stabilizing in late 2024 and early 2025, the unemployment rate is climbing again while job vacancies continue to decline.

June showed slight improvement from May, but we haven’t likely reached a peak in the unemployment cycle.

This softness, however, is hardly an emerging trend. The unemployment rate has been on the rise for the better part of three years, following a post-pandemic recovery that drove the jobless rate down to a 53-year low—triggering robust wage growth as employers competed for workers.

But, the underlying dynamics in Canada’s labour market have evolved significantly. In the wake of the pandemic, rising unemployment primarily reflected the slow absorption of new entrants into the workforce—particularly recent graduates and newcomers—who struggled to find work.

Now, permanent layoffs are not significantly higher than a year ago, but workers are taking longer to find jobs, and there are clearer signs of job losses in sectors vulnerable to cross-border trade. That’s created fault lines across specific regions and demographics.

New labour market entrants are also keeping upward pressure on the unemployment rate despite significant deceleration in Canada’s population growth.

Job losses concentrated in few industries

Tariff anxiety has dampened hiring intentions throughout the economy, but actual job losses remain largely concentrated in trade-related sectors. Manufacturing, primary resources, transportation and warehousing, and certain services outside of public administration1 have borne the brunt of recent employment declines.

Uncertainty surrounding U.S. trade policy appears to be driving much of the weakness, but other factors—like fluctuating commodity prices and a slowdown in homebuilding—are likely intensifying these challenges.

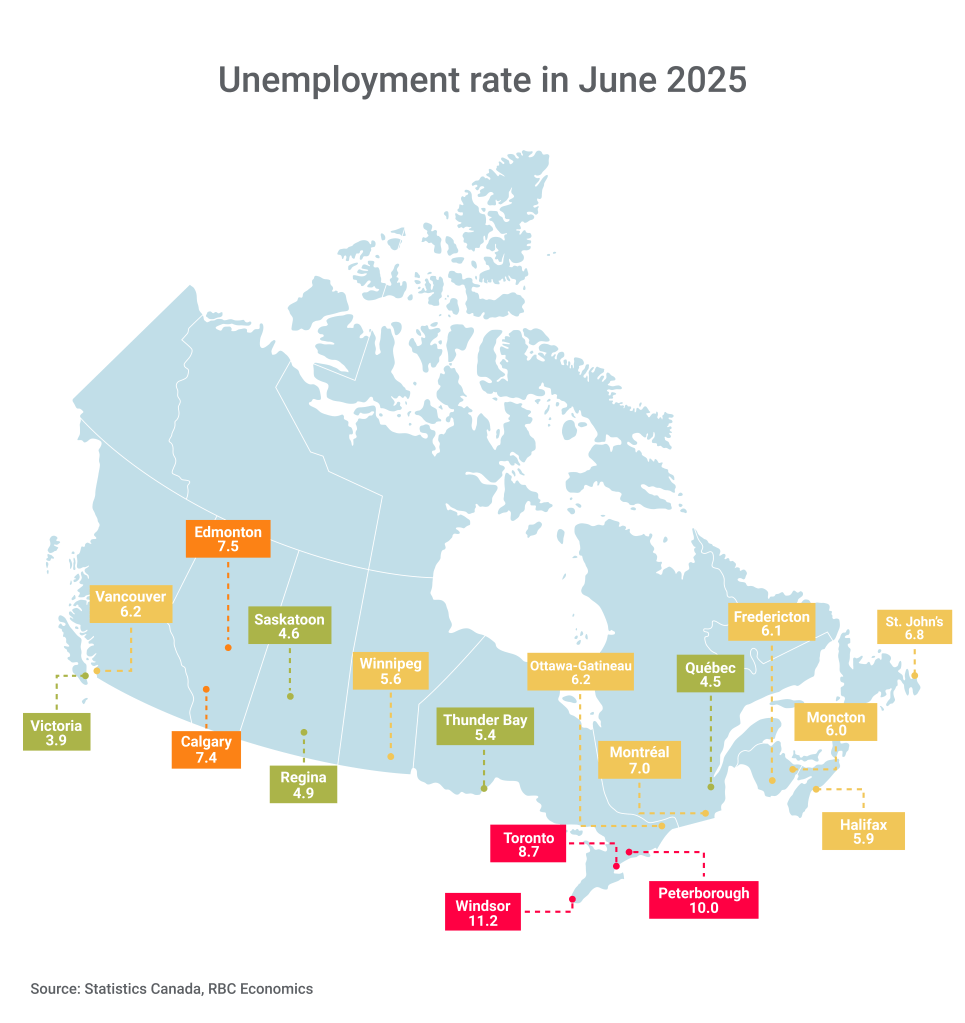

Labour market weakness is regional in Canada

Ontario—the heart of Canada’s manufacturing workforce—is where most of the labour market slack has built up, accounting for more than 60% of the unemployment rate increase since 12 months ago.

Weakness has been especially acute in the southwestern region where most of the province’s manufacturing production takes place. In fact, four of the five highest unemployment rates of any Canadian census metropolitan area were in Ontario including Windsor (11.2%), Peterborough (10%), Oshawa (9.3%) and Toronto (8.7%). Together, these jurisdictions account for nearly a quarter (22%) of Canada’s manufacturing workforce—which shed nearly 45,000 jobs since January (seasonally adjusted)—making it the largest employment decline in any sector this year.

Quebec and British Columbia are also contributing to the national unemployment rate increase with Quebec’s substantial manufacturing workforce (30% of Canada’s total) facing similar trade-related pressures.

Unlike Canada’s largest provinces, B.C.’s rising unemployment rate appears to be stemming from other cyclical factors—like the completion of major infrastructure projects—rather than slowing export activity. Despite these increases, the jobless rate for these provinces is among the lowest in Canada.

In contrast, Atlantic Canada shows remarkable resilience. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick have seen unemployment rates fall below the national average in Q2—a rare occurrence given the industry and demographic composition of these provinces.

Similarly, parts of the Prairies are showing strength with Saskatchewan now boasting Canada’s lowest unemployment rate (4.9%) after seeing steady declines since late 2024. Pockets of Alberta—including Red Deer and Lethbridge—are also seeing labour markets strengthen.

Challenges for late-career and Canadian-born workers

Varying labour market trends can be seen among age groups as well. Late-career workers (aged 45-plus) are experiencing the most acute softening, accounting for nearly 40% of the unemployment rate increase since a year ago.

Core career (aged 35-44) accounted for a quarter (25%), while early career (aged 15-24) contributed a slightly larger 31% to the increase. Early-to-mid career (aged 25-34), however, have contributed significantly less (9%) to the overall unemployment rate increase.

The Canadian-born workforce is also facing more pronounced challenges compared to newcomers, driving roughly 60% of the unemployment rate increase in the last year.

Recent permanent residents are among the only group to see the unemployment rate fall in the last year but, higher vacancy rates suggest this is likely due to a shrinking workforce rather than improved job prospects.

These trends mark a significant shift from recent years when new labour market entrants—particularly recent graduates and immigrants—accounted for the bulk of the unemployment rise.

Growing labour market weakness among Canadian-born and core-to-late career-aged workers likely stems from the concentrated nature of industry-specific softness. Indeed, goods-producing sectors employ a disproportionately high share of late career-aged workers, making them particularly vulnerable to current economic headwinds.

Economic uncertainty also appears to be encouraging some retirees to re-enter the job market as volatile equity markets create financial unease—particularly for those living on a fixed income. This pattern is shown by recent increases in job-seeking activity among those 55 and older who had recently left the workforce.

Rachel Battaglia is an economist at RBC. She is a member of the Macro and Regional Analysis Group, providing analysis for the provincial macroeconomic outlook.

- Primarily engaged in repairing, or performing general or routine maintenance, on motor vehicles, machinery, equipment, and other products. This category also includes personal and laundry services as well as religious, grant-making, civic, professional, and private household services. ↩︎

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.