By Jordan Brennan, Head of RBC Thought Leadership

There was a volley of compliments, smiles and backslaps between Donald Trump and Mark Carney during their meeting earlier this week, with the U.S. President telling reporters that Canada was going to walk away “very happy.” But optimism had come crashing down by the next day, with the U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick telling a Toronto audience that “car assembly is going to be in America and there is nothing Canada can do about it.”

The view from the White House is that Americans don’t need Canada to assemble their cars. It’s difficult to know what to make of Secretary Lutnick’s remarks. Is it a genuine threat or “art of the deal” bravado in which Trump asks for the sun, the moon and the stars and ends up settling for the moon? Word on the street is that President Trump doesn’t like being told “America needs Canadian oil, steel, lumber” and so on.

A Canadian trade team remains in Washington to chase sectoral deals on steel, aluminum, energy and autos—a hallmark of what Washington now calls “managed trade.” With little material progress to date, and an American negotiating team that’s bogged down in bilateral deals with many other countries, it’s an open question if Canada will be able to secure meaningful sectoral agreements prior to the formal review of CUSMA next July.

It looks like “managed trade” is here to stay for now. But what does that mean?

In June, Trump doubled tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum to 50%, up from the 25% rate announced in February. The impact was immediate. Canada produces roughly 13 million tonnes of primary steel annually, exporting half—and nine out of every ten tonnes goes to the U.S. Those flows are now drying up.

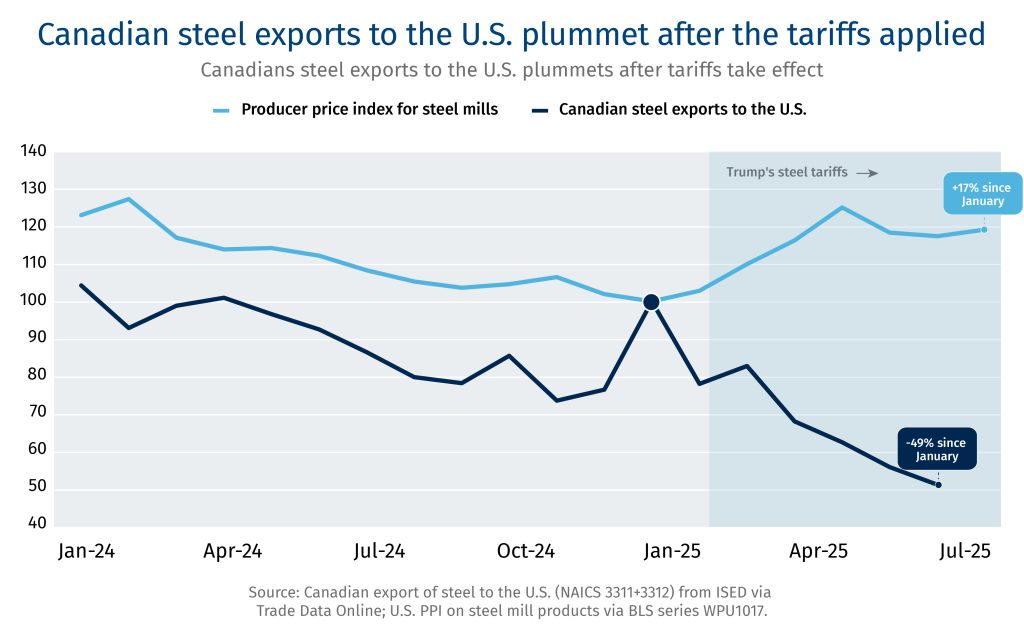

Steel prices tell the story. The chart below shows the value of Canadian steel exports to the U.S. and U.S. steel prices, both indexed to 100 in January 2025 to simplify the comparison. In the 12 months leading up to Trump’s tariffs, Canada’s steel exports to the U.S. and American steel prices both trended downward. Then came the trade war and the two series diverged—Canadian steel exports fell off a cliff while American steel prices marched north.

The new tariffs have reignited steel price inflation. With Canadian imports throttled, American producers are facing less competition and are quietly raising prices. U.S. steel imports from Canada are down 49% while steel prices are up 17% since January.

This is the face of managed trade. It isn’t about opening markets; it’s about organizing them. Under the free-trade order of the past four decades, governments agreed to minimal barriers and let consumer preferences, technology, and competition sort out winners and losers. Managed trade flips that logic. Governments pick strategic sectors, shield them from global competition, and steer investment through tariffs, quotas, and subsidies.

For Canada, the question isn’t whether we like it—it’s how we adapt to it. Ottawa looks ready to pivot, having announced a suite of sector supports in September. We need to learn to play by the new set of rules: identify national priorities, deploy capital strategically, and make reciprocity work in our favour.

Managed trade may be messy. But in this new era, it’s the only game on the field.

The week that was

-

Donald Trump wants his team to “quickly land deals” with Canada. So said Canada-U.S. Trade Minister Dominic LeBlanc after the U.S. President met with Prime Minister Mark Carney in Washington. LeBlanc remains in Washington to continue trade talks.

-

China unveiled sweeping export controls on rare earths. Trump has threatened ‘massive’ tariffs on Beijing in retaliation.

-

Industry Minister Melanie Joly unveiled a three-point plan as part of an effort to counter U.S. tariffs. Itfocused on protecting jobs, creating new ones and attracting both investment and talent.

-

The U.S. has collected US$195 billion in custom duties during the 2025 fiscal year. That figure stood at US$77 billion in 2024.

-

Chips and other AI-related goods contributed nearly half of global trade growth in the first half of 2025, according to the World Trade Organization. The impact of tariffs is expected to really kick in next year—the WTO expects trade to grow a paltry 0.5% in 2026.

Tariff in the top U.S. court

Mark November 5 in your diaries. That’s the day the U.S. Supreme Court will hear the case of President Donald Trump’s emergency tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). The Department of Justice (DoJ) will be hoping to overturn a decision in May by the Court of International Trade that declared that Trump had overstepped IEEPA when he used the law against Canada and other U.S. trade partners.

The case combines three separate cases claiming Trump’s tariffs on Canada, China, Mexico and other trade partners are illegal. One was brought by Democratic state attorneys general, while the other two are from separate coalitions of small businesses.

Here’s what you need to know:

-

It’s “illegal”: The plaintiffs’ central argument is that the tariffs were never designed to deal with the specific U.S. grievances against Canada, Mexico and China over drug-trafficking.

-

Trump has been losing—so far: A three-judge Court of International Trade panel, a federal district judge in Washington, D.C., and the 11 active judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit backed the plaintiffs in a 7-4 decision. The DoJ is hoping the Supreme Court will overturn the “incoherent” rulings.

-

The Supreme Court could go either way: The wins in lower courts could be overturned. It’s a “coin flip,” according to Scott Lincicome, a trade expert with the Cato Institute.

-

The White House has many other tools: Some analysts suggest the Supreme Court could side with the lower courts as the U.S. administration has many another avenues to replace the IEEPA tariffs, such as Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962.

-

Refund bonanza: If the challengers are successful, it could spark a wave of legal battle over refunds of well over US$80 billion.

The Supreme Court ruling could come by the end of the year.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.