Seesawing trade relationships between the U.S. and China have brought critical minerals to the forefront. In fact, Rare Earth Elements (REEs), the 17 elements with physical and chemical properties that make them key inputs to some of the world’s most critical technologies, were China’s latest weapon in its trade arsenal against the U.S.

Following recent trade talks with the U.S., China expressed a willingness to walk back the REE export restrictions it announced in April. However, the threat re-emphasized the West’s collective dependence on China. In September 2020, the first Trump administration signed an executive order warning of the country’s critical dependence on China for REEs and called for increased domestic production. Even if the U.S.’s attempts at re-shoring supply are successful, its production will be a fraction of China’s, making international collaboration, including with Canada, a critical requirement.

Seven numbers tell the current state—and Canada’s potential role.

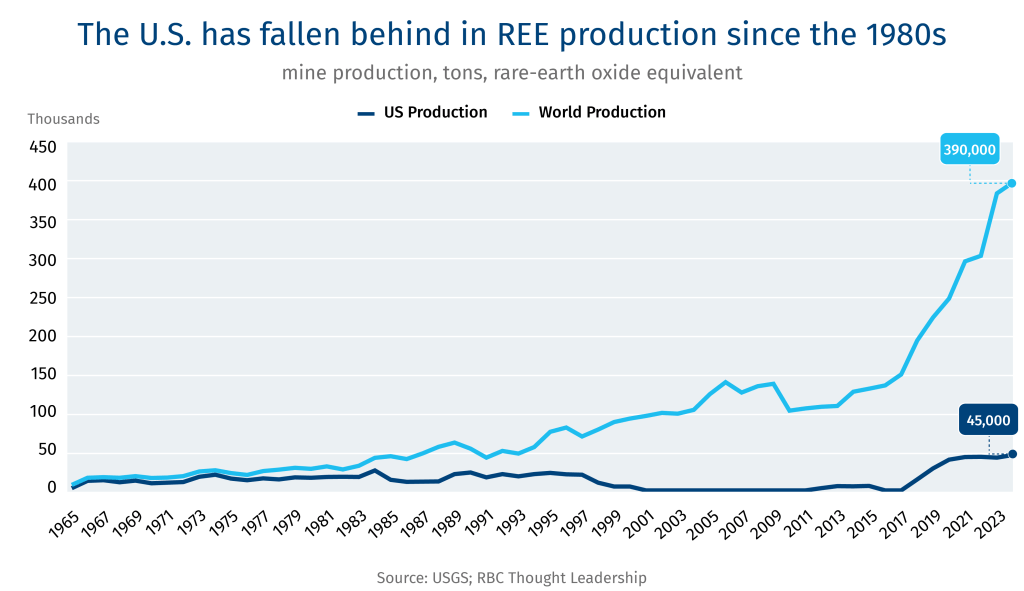

67%

Share of global REE mine production that comes from China. While the U.S. produces 11% of the global total, the second highest, it exports nearly all its production for further processing. The U.S. was once the world’s leading REE producer but has been losing share since the 1980s, with China dominating global production since. Canada has produced REEs in the past, but currently does not have any domestic mining operations.

99%

Share of Chinese control over Heavy REE separation and processing. Heavy Rare Earths, such as terbium, enable REE magnets to work in higher temperature applications without losing performance. China also controls 90% of Light REEs, including neodymium, which are also key inputs to magnets. Countries like Estonia and Canada have or are developing LREE and HREE separation and processing capabilities.

92%

Share of Chinese control of global REE magnet manufacturing. While REEs are used in various forms (e.g., as powders for polishing optical equipment, and as catalysts in petroleum refining), they are also used to make the world’s most powerful permanent magnets. These magnets are used in high-performance technology including military aircraft, submarines, and electronics and are difficult to substitute.

16

The number of U.S.-entities to which REE exports were banned by China in April, as trade tensions between the two nations escalated. Fifteen of these entities were linked to the manufacturing of defense technologies.

US$439 Million

How much the U.S. Department of Defense has spent since 2020 to strengthen its domestic REE supply chain.

$22 Million

What the U.S. has invested in Canadian REE processing companies since 2023. Canada is considered a “domestic source” of critical minerals under the U.S. Defense Production Act (DPA), so Canadian companies are eligible to receive investments under DPA Title III.

12

REE projects in Canada currently active in the exploration, resource estimation, or preliminary economic assessment phases. There are also three separation and processing facilities and two REE recycling plants. To capitalize on the opportunity, a few things could speed things along. 1/ Government investment: Provincial funding in Saskatchewan, for example, has helped bring REE processing facilities closer to commerciality. Government support could also help fast-track projects. 2/ Secure offtake for REE products: As discussed in The New Great Game, decades of focused industrial policy and technology development have left Western manufacturers competing with lower-cost products while being bound to tighter environmental standards. Guaranteed offtake at competitive prices could help Canada’s REE industry get a foothold.

Vivan Sorab is Senior Manager, Clean Technology, at the RBC Climate Action Institute

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.