Artificial Intelligence is poised to reshape how value is created across Canada’s economy. To understand that shift, RBC Thought Leadership interviewed more than two dozen firms that are on the frontlines of building or deploying AI for Bridging the Imagination Gap: How Canadian Companies Can Become Global Leaders in AI Adoption. The report distilled the patterns that emerged from those conversations.

Building on that report, our series of case studies goes a level deeper. Here we follow how Manulife, a global insurer and asset manager, used generative AI as a catalyst to rethink how the organization learns, shares, and scales new ideas. The company’s experience shows that successful AI adoption is not a technology challenge alone—it’s a challenge of capability-building, governance, and empowering people to work differently.

Summary

Manulife, a global asset manager headquartered in Canada, saw AI as a chance to move beyond incremental efficiency gains and reimagine products and operations. Leadership judged the sector “too comfortable,” set a clear ambition to become a digital-customer leader, and treated OpenAI’s Large Language Model in 2022 as a tipping point. A hands-on executive session turned AI from a niche experiment into a CEO-level agenda item, signalling that real impact would require structure, governance, and integration—not one-off pilots.

Build absorptive capacity (infrastructure). Manulife created a multi-tier learning stack and embedded ~200 data science and machine learning experts, and used leadership rituals to grow the “stock of prior knowledge,” so new AI advances could be absorbed and embedded faster.

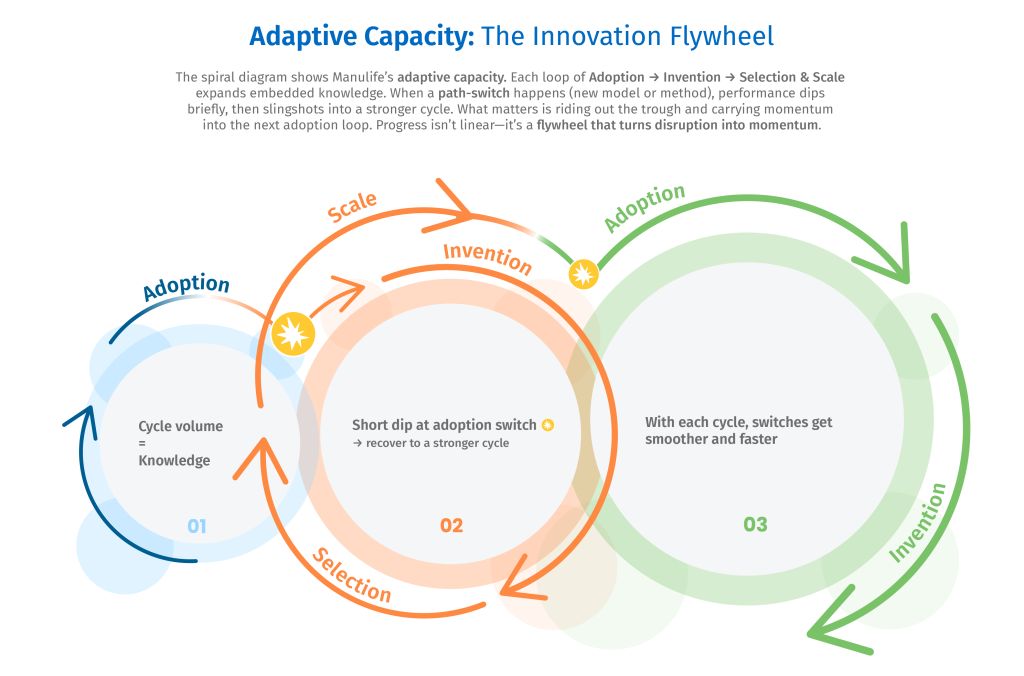

Institutionalize adaptive capacity (the engine). Leaders normalized copying—if one team built something useful, others reused it. This turned isolated wins into shared playbooks and spread improvements quickly. By embedding that habit, Manulife accelerated the cycle of adopt, invent, select, scale, building adaptive and innovative capacity together.

Balance speed and safety (governance by outcomes). Responsible AI principles, expanded model-risk frameworks, cross-functional review, and real-time telemetry treated fast iteration and strong oversight as complements, not one-off pilots

It was mid 2020. Jodie Wallis, then Manulife’s Global Chief Analytics Officer, had summoned the company’s top executives into a Toronto boardroom. She knew the meeting would mark a turning point: OpenAI’s breakthrough latest large language model (LLM), GPT1– 2 had just been released, and, at nearly 100 times stronger than its previous models, GPT-2’s implications stretched far beyond the technology itself. For Manulife, a 137-year-old insurer built on actuarial precision and risk discipline, the question was whether this new capability would be treated as a passing novelty, or as the spark for deeper change.

For years, AI at Manulife meant prediction and automation—underwriting models, fraud detection, lead scoring. Even as the frontier advanced with machine-learning models that could conjure hyper-realistic images, these applications still felt contained within the realm of “computer things.” They were useful and very impressive but safely bounded by expectation.

To Wallis, large language models like GPT shattered those boundaries. Designed for an iterative exchange, they created value not through a single output but through an unfolding dialogue—shifting the dynamic from command-and-response to something closer to collaboration. LLMs could now reason with a human-like cadence, inviting conversation rather than instruction. The breakthrough was not a more polished “answer,” but the model’s ability to so fluidly augment inquiry itself—generating new directions of thought and discovery.

That shift—from bounded tasks to open-ended discovery—was as unsettling as it was exhilarating. Wallis framed the moment with unusual candor: “Our industry has been too comfortable. This technology isn’t just another tool—it’s a fork in the road. We either harness it, or risk being reshaped by it.”

Around the table, reactions varied: curiosity, excitement, apprehension. The challenge was immediate. Should Manulife treat generative AI as an experiment at the margins, or as the new trajectory of the business itself? Wallis herself was convinced of the answer, but she also knew the technology was still raw—too raw, perhaps, for the boardroom to fully accept. The choice would force hard calls about strategy, governance, culture, and investment, all at the breakneck pace at which the frontier was advancing.

In such moments of technological upheaval, corporate boards look to figures like Wallis to distinguish passing trends from transformative forces. Unlike the technologist-soothsayers popular at the time, her task was consequential: to foresee how generative AI might reshape an institution built on actuarial discipline, and to ensure Manulife seized the opportunity rather than being undone by it. Frame the moment correctly, and new value could be unlocked; misjudge it, and the consequences could be existential.

But foresight alone would not suffice. Wallis knew no memo or slide deck could capture the implications of generative AI; words on a page risked being dismissed as abstractions. The only way forward was direct confrontation. To overcome that gap, one had to experience it themselves. Fortunately, the technology itself offered an answer—the opportunity to turn the crystal ball around and let skeptical peers glimpse inside for themselves.

So, she placed a tablet in front of each leader, preloaded with the latest OpenAI model, and invited them to test it—to ask it the questions they might otherwise have asked her. The room fell silent as screens lit up with blinking prompts. One by one, Manulife’s senior leaders began conversing with GPT-2, watching as it generated fluent answers in real time. The exercise was disarmingly simple, yet it shifted the atmosphere. Within minutes, the conversation had moved from “is this real?” to “what does this mean for us?”—the kind of pivot that months of memos and meetings could never have achieved.

It was Wallis’s decision—to make her colleagues experience the frontier for themselves—that created conviction at the top. But she knew conviction alone would not be enough. To matter, it had to be built into infrastructure, and then into the agility to adapt. With that boardroom experiment, Wallis set the flywheel in motion—conviction, infrastructure, adaptation—that would carry Manulife through one of the most profound technological shifts in its history. In doing so, Manulife joined a small group of financial giants positioning Canada at the forefront of AI transformation.

To understand how this journey unfolded, RBC Thought Leadership sat down with Jason MacDonald, Chief of Staff in the Office of the CEO, and Jodie Wallis—now the company’s Global Chief AI Officer—to explore how they and their colleagues steered a $72-billion insurer through one of the most profound technological shifts in its history.

Results: From Experiment to Enterprise Transformation

Within just a year of embracing generative AI, Manulife achieved broad-based adoption at a speed few incumbents match. Its proprietary assistant, ChatMFC, went from pilot to near ubiquity: within months, 40% of employees were using it monthly, and by early 2025, more than 75% of the global workforce was actively engaged with GenAI tools, training, or use cases. Adoption was not siloed to tech teams; it touched nearly every function, from sales and service to back-office operations.

The impact on productivity was equally striking. In call centers, AI tools shaved 30 – 40 seconds off average call times without lowering customer satisfaction. Across the enterprise, generative AI was no longer a side project—it had become embedded in the daily flow of work.

Customer-facing gains were even more visible. Newer advisors ramped up faster, using AI coaching to practice and refine interactions. Meanwhile, advisors reported that AI freed them to focus on client relationships, creating the unusual outcome of a technology initiative that delivered both efficiency and deeper human engagement.

At the strategic level, the flywheel was spinning. By mid-2025, Manulife had 35+ GenAI use cases in production and 70 more in queue. Early deployments alone contributed an estimated $4.7 million in benefits, while the broader digital transformation program (with AI at its core) yielded over $600 million in 2024 benefits—savings, new sales, and better risk outcomes. Looking ahead, the company projects a threefold return on AI investments over five years. These results affirm that Manulife’s design choices — hands-on executive engagement, outcome-gated scaling, perpetual-beta governance—transformed AI from novelty to institutional capability.

Numbers

| $1.6T | Assets under management |

| 35M | Customers worldwide |

| $53B | Market Capitalization |

| $5.1B | Net Income |

| 38k | Number of employees |

| 200 | Data scientists and engineers embedded across teams |

| $600m | Benefits attributed to digital transformation (with AI as a core part) in 2024. |

| 75+ | AI use cases deployed by the end of 2025 |

| 75% | Share of Manulife’s global workforce engaged with GenAI |

Download the Report

Project Lead

Reid McKay, Director Technology Policy, RBC Thought Leadership

Contributors

Nora Bieberstein, Director, Strategic Programs, RBC Thought Leadership

Yadullah Hussain, Managing Editor, RBC Thought leadership

Special thanks to Janice Stein, Founding Director, Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy and Nicole Harris and Avaani Singh, Graduate Students, Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy.

Generative Pre-training Transformer

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.