Key Findings

Canada’s agri-food startups present a $13-billion investment opportunity. Capital flows in growing agri-food companies could help Ottawa achieve its target of unlocking $1 trillion in investment by 2030 to power economic growth.

The country’s agri-food sector is currently undercapitalized by domestic growth funds. The sector accounts for only 2% of government-backed growth, venture and infrastructure funds at the federal level, and brought in an estimated 4% of total growth funds invested in Canada over the past 5 years.

It’s not that there isn’t interest. Venture and institutional funds have attempted to flow but fragmented governance across provinces and sector fit for funds have pushed agri-food to the sidelines of mainstream approaches to deploying growth capital.

Domestic agri-food companies got a piece of the growth capital boom–$10.5 billion–between 2015 and 2021. However, investments across sectors have dwindled. Today, growth investment in Canadian agri-food is lower than it was a decade ago, with values down 32% and deals by 29%.

The basic mechanics of growth for an agri-food company can cut the sector out of fund priorities. To align investment with Canada’s growth and sovereignty ambitions, funds like the $1B Venture and Growth Capital Initiative announced in the 2025 federal budget could establish agri-food lanes with tailored tools.

Other nations–including Finland, Japan, and the United Arab Emirates–are explicitly linking food security, productivity, and industrial policy through coordinated growth capital strategies. To achieve food security goals, the UAE launched the Agri-Food Growth and Water Abundance (AGWA) cluster with the ambition to attract $48 billion by 2045 specifically for their agriculture, food and water sectors.

The opportunity for Canadian investors and innovators–public and private–is to better calibrate and scale capital and businesses to anchor economic value domestically. This starts at the idea stage, improving universities’ weakening role in innovation and reverse trends in business outsourced investments to universities for agri-food R&D, which have fallen 64% in the past five years.

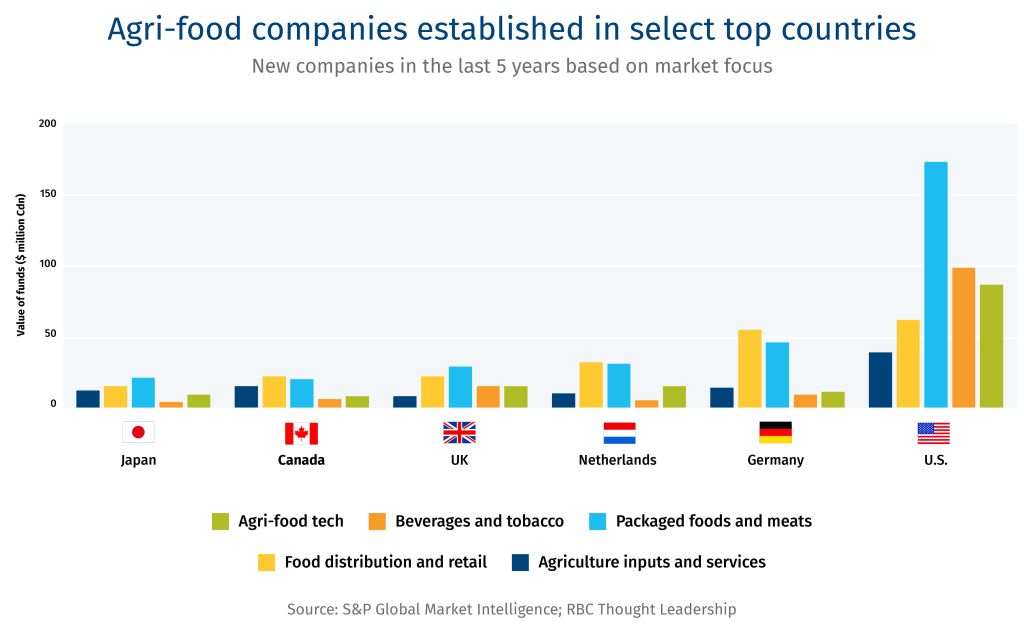

Canada has one of the world’s most productive agricultural systems, globally competitive farmers, and is a net exporter of value-added agriculture and food products. Yet, the country is steadily losing its position as a preferred place to start, scale, and retain agri-fooda startups. That’s because the pipeline for investment and innovation has structural gaps and barriers, from seed to maturity.

Canada is in building mode. Its ambition to attract $1 trillionb in investment over the next five years to drive growth for the country is a signal.1 A key piece of mobilizing this investment is to put Canada’s existing infrastructure, growth, and venture funds to work for potential high-growth sectors, such as agri-food industries. Most notably, the 2025 federal budget identified agri-food as one of three sectors that Canada enjoys a strategic global advantage. But Canadian agri-food accounts for less than 2% of growth-oriented government-backed funds. And over the past five years, agri-food companies have only captured 4% of total growth capitalc investment in Canada, which agri-food investors characterize as a stark under-investment in the sector.

If Canada were to align its growth capital investment in agri-food with the industry’s contribution to GDP as a benchmark to build from, it would require an estimated $13 billion from now until 2030–a 36% boost in investment relative to the past five years. An investment ambition to focus action and position Canada as a thriving, global hub of agri-food innovation and products.

Global disruptions over the past five years highlight the need to advance Canada’s sovereign capacity in agriculture and food innovation, production and processing. And the rest of the world is not waiting for Canada to perfect its approach. Without immediate action, Canada risks capping agri-food sector’s growth potential by not hosting more value-add processing domestically. It risks hollowing out the agri-food innovation ecosystem as companies and talent look to other countries, including Australia, Japan and Germany, which are growing their investment in R&D and commercialization.2 And it risks irrelevance in the era of disruptive technologies—including AI-driven decision tools, gene editing, biological inputs, automation, robotics, and novel food processing—that will shape productivity gains in the decades ahead.

There is a mismatch between the framing of Canada’s agri-food sector as a superpower and its strategic advantages with the actual scale and focus of investments domestically. Transforming Canada into an agri-food superpower requires a targeted, nimble approach to capital and growth that navigates the sector’s restraints and fulfills its true potential.

The investment pipeline

-

Purpose of capital: Idea development, early prototyping, market research

-

Investors: Angel investors, incubators/accelerators, university and government grants, venture seed funds, family offices

-

Strengths: Government and regionalized support via early-stage innovation programs

-

Challenge: Breakdown between public and private collaboration on commercialization of intellectual property (IP)

-

Purpose of capital: Pilots, prototyping, market testing, and small-scale production

-

Investors: Accelerators, venture firms, corporate venture, government grants, family offices, Crown corporations

-

Strengths: Growing network of venture funds

-

Challenges: Navigating investment pathways and undercapitalization risks that could force bridging rounds, slow development, and dilute equity

-

Purpose of capital: Continued innovation, market leadership emerging, scaling operations

-

Investors: Venture firms, private equity, corporate strategic investment, Crown corporations

-

Strengths: Access to international market for capital, especially U.S. and EU

-

Challenges: Gap in follow-on fund, especially Series B to growth and fragmented domestic capital-raising options

-

Purpose of capital: Stable cash flows, slower growth, operational efficiency and expansion, exit

-

Investors: Commercial banks, private equity, merger and acquisition, trade sale, initial public offering

-

Strengths: Strong commercial bank support, however, project financing can be difficult to secure

-

Challenges: Few large domestic corporate acquirers; often requires sale to foreign buyers; Companies with infrastructure projects face structural challenges in assembling capital mixes

Canada’s agri-food growth capital dilemma

Not enough companies make it to growth; and not enough capital is available for the select few that do.

The scale, staging, and value of growth capital invested in growing companies are indicators of a sector’s momentum and growth prospects. In Canada, upstream and midstream marketsd that cover agriculture inputs to food processing is generally well covered for early-stage capital by government grants, family offices, and venture firms. While end-stream markets like food brands have less access to early stage-funds, with fewer active venture firms in the market. Agri-food companies across market segments start to face Canada’s growth capital challenge of fragmented and shallow domestic funds when seeking to raise $15 million in capital or more. And across economic sectors, there is a significant gap in capital for growth, with domestic venture firms not positioned to inject more than $30 million. This constrains scaling and reduces Canada’s ability to attract and retain high-potential agri-food companies. The situation is exacerbated as agri-food in Canada is too complex for general investors to navigate without industry expertise. The capital pools, for example, engaging with an agriculture-tech company are often completely different from those engaged with a food brand company as their growth metrics, markets, and use of capital differ substantially (e.g., IP vs. a distribution warehouse).

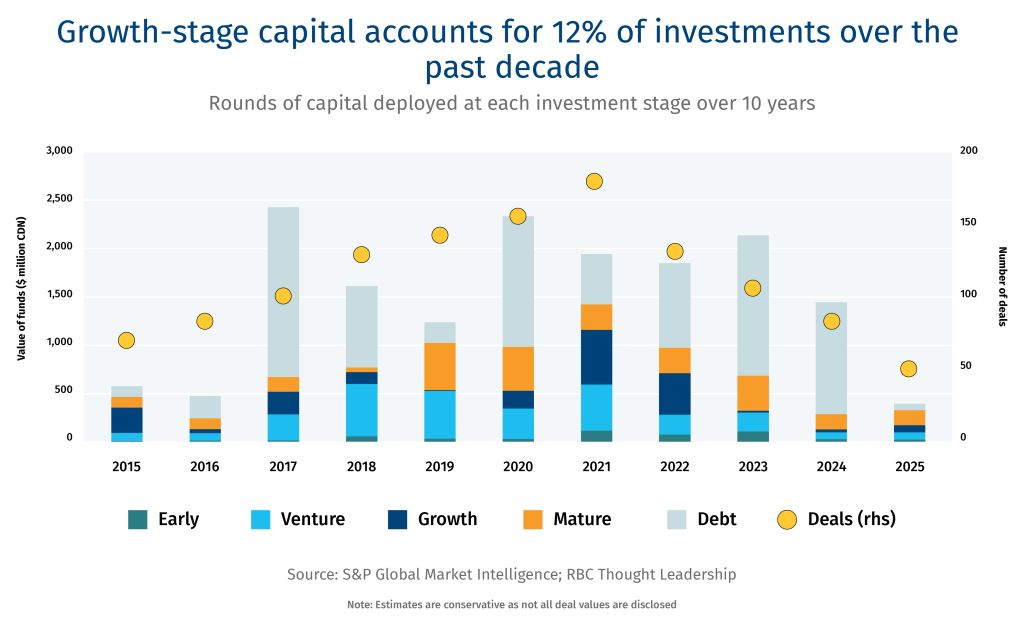

The growth capital market has had a volatile decade. The world experienced a surge in growth capital across sectors, including agri-food, in the lead up to the peak in 2021. Between 2015 and 2021, growth capital in Canadian agri-food in the early and venture stages grew by 1,405% and 480%, respectively.3 This growth was driven by a few factors, and actors:

-

Global interest in agri-food technology and sustainable agriculture surged with the growing urgency to feed more people with fewer environmental impacts. As a result, global investment in agri-food technology rose to $71 billion in 2021.4

-

In response, Canada launched incubators (YSpace Food Incubator), accelerators (SVG Thrive) and applied food science centres (Saskatchewan Food Industry Development Centre) to enable commercialization of agri-food innovation.

-

Agriculture and food focused venture funds also grew in Canada, including District Ventures Capital, Ag Capital Canada, Emmertech, Tall Grass Ventures, and Nya Ventures.

-

And some crown corporations helped drive momentum in the sector through initiatives like Farm Credit Canada’s (FCC) $2 billion commitment by 2030 to advance innovation in the domestic agriculture and food industry.

Since 2021, most segments of growth capital availability and investments have dwindled. Investment in Canadian agri-food companies is now lower than it was a decade ago, with values down 32% and deal count by 29%.5 This contraction mirrors trends in other major agri-food economies—including the U.S., Brazil, and Australia—where funding focused on agri-food technologies dropped to a 10-year low.6

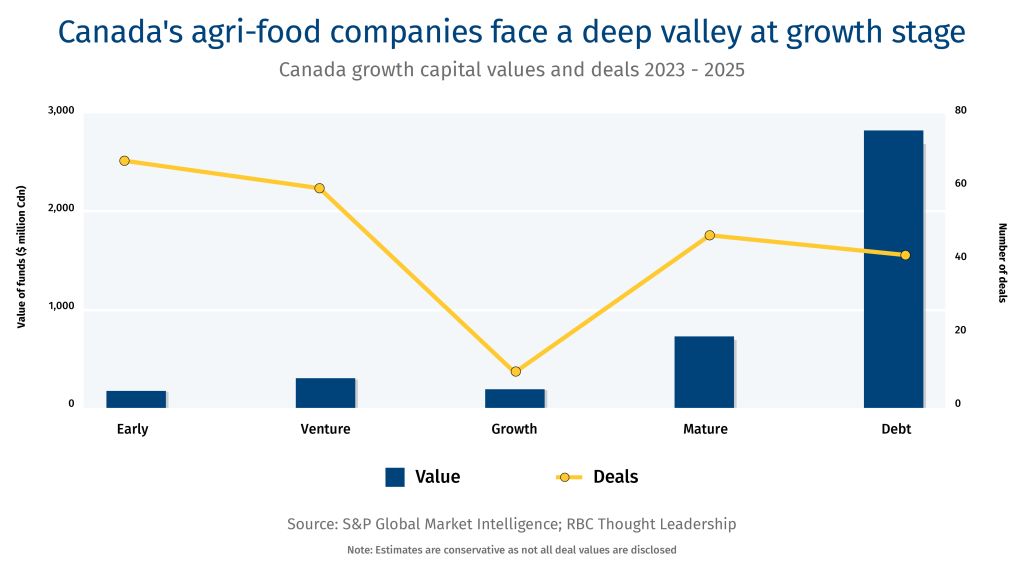

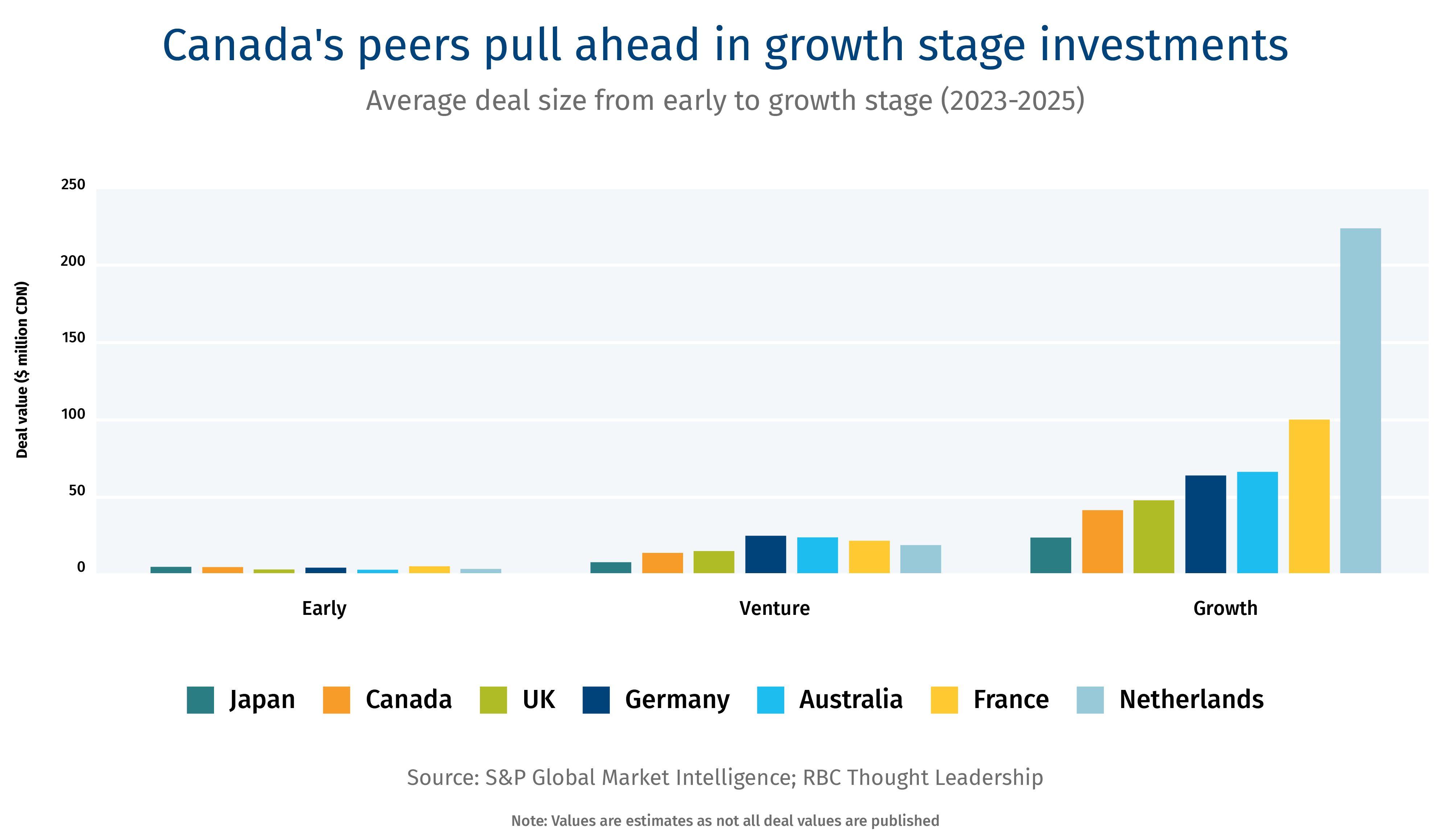

While there have been some positive signs in the past five years, such as rising private equity and a shift to focusing on impactful and mature companies, fundamental challenges in retaining and attracting capital remain. The most obvious challenge is the growth-stage. The value of available capital in Canada in growth stages falls roughly 37% compared to the venture stage where the startups are more supported by venture firms and incubators.7

However, focusing on fixing this problem in isolation, can result in new problems arising along the pipeline. For example, the agri-food venture funds that emerged over the past decade in Canada now seek to raise new, larger funds to address gaps at the growth capital stage, and this shift could risk creating a new gap in early venture—rounds of between $1 million and $5 million. Enabling capital availability at each stage of growth and across market segments therefore requires coordination among investors to build coverage along the pipeline.

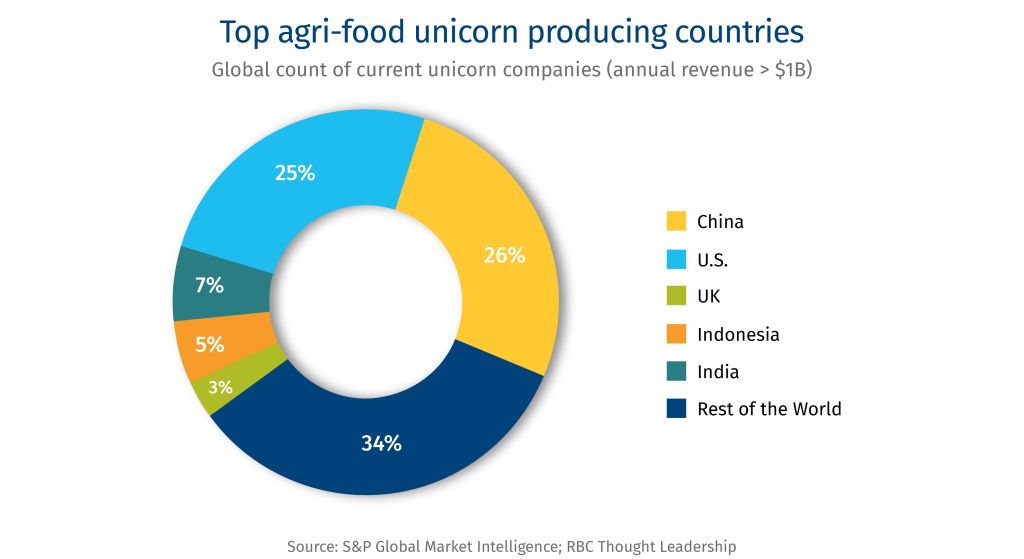

The absence of a Canadian agri-food unicorn—defined as a privately held startup valued at more than $1 billion—is a macro signal that Canada does not have an ecosystem that can propel promising companies.8 Peers like the Netherlands, Germany, and Australia all have unicorns—and heavy hitters like the U.S., India, and China have a stable-full.

Canada’s capital roadblocks

Low capital, slow growth

Capital structures push companies down and out of Canada.

Canada’s agri-food startups often advance slower through their commercialization and market expansion stages relative to those in competing markets because capital pools are shallower. Less capital leads to incremental growth and longer time horizons to demonstrate returns. While early-stage companies can attract public and venture funding, those seeking larger rounds are often forced to seek capital abroad.

Vive, a crop protection company based in Mississauga, Ontario, is looking to raise Series D capital, seeking more than $40 million, starting in Q1 of 2026. Vive expects that more than 75% of the capital raised in this round will come from outside Canada. This builds on Vive’s initial market expansion, which occurred in the U.S. because the active ingredient approval for their products took four years compared to the eight years it took in Canada.

Concentrated, and restricted government capital

Fueling early agri-food innovations but avoiding support for those same innovations at growth stages.

Support from government at the early stages of growth comes largely from incubators, accelerators, cost-share and R&D programs, which are important pieces of Canada’s agri-food innovation pipeline. Yet, this concentration and program delivery often results in Canada’s emerging leaders in agri-food being described as “grant-entrepreneurs” who are forced to spend excessive time on finding and writing applications and meeting reporting requirements instead of building investor-ready businesses. Of course, government checks and balances are vital in public funding, but accessing and reporting on these funds can be made more efficient.

Another challenge with government capital is that economy-wide pools of funds like the Canada Growth Fund do not intentionally restrict agri-food, but the sector often does not fit neatly within investment criteria for several reasons, including project scales, geographical dispersion of production and projects, and the definitions of innovation or clean technology. As a result:

-

Canada Growth Fund’s 17+ investments do not feature a single agri-food company.

-

Of Canada Infrastructure Bank’s 106 investments, only one is focused on agriculture production.

-

The agri-food sector makes up an estimated 3% of the 575 companies invested in through the Venture Capital Catalyst Initiative (VCCI) and Venture Capital Action Plan.

Untouchable wealth

Capital from asset-tied farmers to blocked out institutional investors is an untapped resource for Canada’s agri-food sector.

Institutional investors in Canada, like pensionfunds and private equity firms, want to be engaged in Canadian agri-food but face a trifecta of investment barriers:

-

Limited number of sizeable projects

-

Co-investors, both private and public, to share risk

-

Investment-limiting regulations

Canada’s model for capital attraction in primary agriculture illustrates some of these barriers. Canada is optimized for family ownership with differing provincial regulations on ownership restrictions including foreign investment and supply management for some sub-sectors. This is in sharp contrast to Australia, for example, which treats agriculture as an investable export industry via large, aggregated farms with professional farm management companies. Investors can inject hundreds of millions into single companies, who then have more liquidity to make investments in new companies and innovations that can boost their productivity.

Institutional investors looking to make significant investments with proven returns might see Canada’s fragmented model difficult to navigate. As a result, some of Canada’s largest pension funds invest in agriculture outside of Canada. Public Service Pension Investment’s natural resource portfolio is made up of roughly 77% agri-food investments, with Canada accounting for 9.3%. The largest share, 43.3%, goes to Oceania countries, predominately Australia.

Farmers also have an important role in the agri-food innovation and capital pipeline as new products and services in the upstream market segment can directly impact their growth and productivity. But Canadian farmers are limited since capital is often tied up in operational costs and assets, like land, buildings and equipment. This reduces both demand signals for novel technologies and co-investment opportunities in impactful projects relative to countries that can attract large-scale investments at the farm-level and have available capital for expenditures beyond operations and assets.

Cautious capital

Risk aversion dampens investor appetite, entrepreneurship, and innovation.

Unlike the U.S., where a “fail fast, iterate, scale” culture fuels deal activity and risk appetite, Canadian investors are generally more risk-averse, particularly beyond seed stage, which discourages bold bets. This shows up in the number of new Canadian companies seeking funding rounds.

Traditional investor preferences toward, for example, information technology over agri-food innovation —often perceived as lower-growth and lower-return—limit participation by generalist venture firms and institutional investors. This reinforces narrow capital pools for late-stage agri-food deals.

The onus to build clear and consistent approaches to access support and capital should not lie solely with investors. If startups can get customers, capital often follows. This stresses the need for improving the applicability of new innovations to real-world problems and the adoption of these innovations alongside investment, starting with Canadian farmers, corporates and retailers but also foreign customers for Canadian companies to truly scale.

Proven demand would enable startups to forge capital paths through their growth stages and work with investors to build the right capital stacks. Three Farmers, a Saskatchewan-based snack food company, scaled production in the Prairies and sells its seasoned pulses in more than 4,000 retailers across Canada and the U.S. Attracting growth capital has been a key component of the company’s success. That includes a 2022 raise of $6.2 million led by three pivotal investors: Venture capital firm District Ventures Capital who has deep consumer packaged goods expertise, Export Development Canada how helps companies effectively grow in foreign markets like the U.S., and Protein Industries Canada who can offer access to innovation and supply chain networks.9 In 2025, a new strategic partnership with Farm Credit Canada (FCC) added equity but also the smart capital that growing companies need in the form of mentorship to help navigate regulations and optimal approaches to capital mixes. Such examples offer a gameplan on engaging and connecting with the right type of investors—at the right time.

Costly commercialization

Building supply chains requires capital—emerging agri-food companies struggle to source it domestically.

Building out agri-food supply chains and commercializing products often requires infrastructure development for production and processing facilities, which demands the right capital structures across equity and debt to make the developments attractive for companies and investors. Often new facilities for production, especially for food products and processing, require off-take contracts or adoption commitments to secure investor confidence. In Canada, where there is a small pool of investors willing to engage in large capital projects, food supply chains are decentralized, and price benchmarks can be uncertain, particularly for novel food ingredients, obtaining these commitments can be difficult, raising percieved risk.

Despite the upfront cost to commercialize and expand, growth in the industry runs counter to the assumption that momentum is not building for value-add processing in Canada. Over the past decade, year-over-year revenue growth in agri-food manufacturing has averaged 5.9%, compared to the manufacturing average of 3.6%.10

Investment in agri-food manufacturing assets has grown by about 32% in constant prices over the past decade.11 This moderate growth is primarily driven by expansion of established, large scale agri-food companies building out meaningful processing capacity.

Yet, many new companies innovating in food ingredients face barriers in bringing together the right capital stacks due to supply-chain barriers–a lack of price certainty and contractual commitments from buyers before processing infrastructure is built. As a result, Canada risks losing value-add processing to other growing jurisdictions where the capital is flowing it. For example, Phytokana Ingredients Inc., an Alberta startup turning Canadian-grown fava beans into food ingredients, is working to build out Canada’s value-add processing of pulses and is in the process of securing funding to construct and commission a fully automated 30,000-metric-tonne-a-year dry fractionation processing facility near Strathmore, Alberta.12 However, building the right capital base is proving challenging with domestic investors, pushing Phytokana to explore foreign investors, which may have implications for where future value-add processing is developed.

It’s not all about money: Three ‘Cs’ beyond capital to target

Canada’s agri-food landscape is difficult to navigate for startups and investors not ingrained in the network of agri-food regional and national organizations. Once in these networks, startups in the early stages are often well supported, but two challenges to building consistent pathways for companies to attract staged capital remain:

-

Navigating the funding and support opportunities and application processes

-

Identifying where to go for follow-on funding

Mapping investor profiles to specific market segments and their mandates provides a structured roadmap for scaling capital from seed through to growth stages. Countries like the U.K., Israel, and Singapore offer examples of how to build such structure. The U.K., for example, is known for structured paths from seed accelerators and hubs into mid-and late-stage capital with organizations such as Founder Factory.

A key reason why agri-food deal counts in Canada over the past three years shrink by 450% between early to growth stage is the state of startup companies’ readiness. Investors consistently cite company readiness as a primary constraint. Founders of startups often excel at proof-of-concept and R&D but face challenges when transitioning to validated customer demand, repeatable revenue models, regulatory and supply-chain readiness and management and governance maturity.

Many organizations, including university research innovation offices and accelerators, are positioned to work on these issues. For example, the Canadian Food Innovation Network (CFIN) connects startups with corporate partners around defined food technology market segments such as food ingredients. These programs enable startups to build relationships with retailers and strategic buyers earlier, while giving corporates and supply-chain actors clearer visibility into emerging innovations. Making this connection is critical to improving startup success rates and building connectivity among industry leaders and startups, as only 6% of public corporate companies engage in venture investment in Canada, compared to 40% in the U.S.13

Canada is increasingly perceived as a regulatory burdensome place to scale an agri-food business and commercialize its IP in agri-food.

Canada lags key competitors like Australia, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, UK and South Korea as a priority jurisdiction for agri-food patent filing.14 An outcome of multinational companies, especially those in life sciences that reported that they have seen Canada significantly fall in their internal ranking of jurisdictions to invest in R&D over the last decade. This is in part due to approval processes for agri-inputs like active ingredients in pesticides struggling to maintain a timely and transparent process for reviewing applications.15 These trends are chipping away at Canada’s brand as a supporter of early agri-food innovation.

Taking lessons from the best

The Giants

United States: Scale and depth

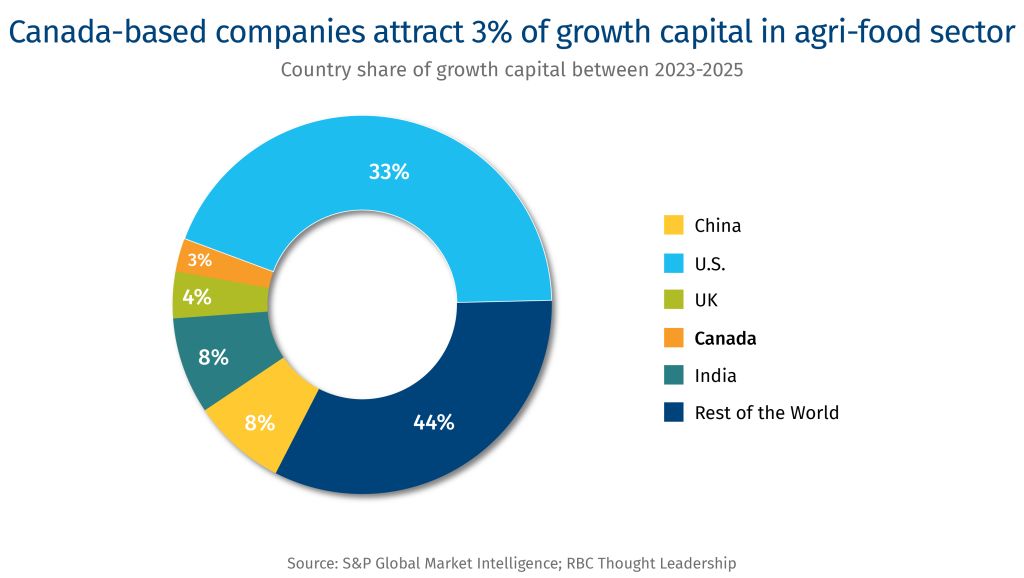

Market share: The U.S. captured 33% of global agri-food investments over the past three years.

Strength: The sheer scale and maturity of its capital markets.

Lesson: Build growth funds that can actively participate across the full company lifecycle. For example, Chicago-based S2G Investments has multiple funds, and can work with companies at different stages of growth, creating deeper capital pools, where agri-food companies have historically struggled to access capital from PE or commercial banks (e.g., pre-revenue).

India: Demand-driven growth

Market share: India now attracts 8% of global agri-food growth investment and is projected to be even more dominate over the next decade as its agriculture productivity rapidly improves.

Strength: Growth is anchored in massive domestic demand, a rapidly modernizing food system, and strong government support for agricultural innovation.

Lesson: Focus on the basics of where production and consumption is growing to steer investment. To meet consumption and production projections, India is experiencing strong growth in agri-marketplace platforms, supply-chain logistics, and precision agriculture through increased participation from domestic venture funds and strategic.

Ones to Watch

- Finland: Aquaculture and deep tech leadership

- Japan: Corporate capital and materials innovation

- United Arab Emirates: Food security as investment strategy

The country now captures nearly 8% of Europe’s agri-food tech investments.16 The recent surge was driven largely by a $260-million growth-stage investment in Finnforel, an aquaculture company, highlighting Finland’s strength in sustainable protein and advanced food production systems.

Despite just 2.3 million hectares of farmland—3.7% of Canada’s farmland mass—Finland is emerging as an innovation hub following a similar government-backed approach that the Netherlands and Denmark have taken to crowd-in private investment for the sector. Finland’s ecosystem is characterized by strong public-private collaboration, deep expertise in cold-climate agriculture and aquaculture, and a focus on export-oriented, high-technology solutions.

Japan is now the third largest agri-food technology investor in Asia capturing an estimated 13% of the market–behind India and China.17 Japan rose in the global rankings on the back of several large growth-stage deals, including a $89-million investment in biomaterials startup Spiber.

Japan’s competitive advantages include active participation by large corporate venture investors, including Global Brain Corporation and Beyond Next Ventures. Japan is a mature domestic market that supports commercialization of premium and functional foods and has notable advantages in key growth areas including biomaterials and fermentation technologies. The country’s domestic ecosystem also excels at scaling capital-intensive technologies that require long development timelines and strong industrial partners.

The UAE imports approximately 80% of its food. In response, food security has become a national priority. The UAE aims to produce 50% of its food domestically and rank first in the Global Food Security Index by 2051.18 To achieve this, the UAE launched the Agri-Food Growth and Water Abundance (AGWA) economic cluster, which aims to attract nearly $48 billion by 2045.

Food security as a strategic imperative has fueled rapid growth in the country’s agri-food sector, and is supported by broader benefits of the UAE’s economy, including:

-

Tax-free zones and investor-friendly regulation

-

Leading logistics infrastructure and a strategic geographic location as a connector between Europe, Africa, and Asia

-

Strong government backing aligned with long-term national goals.

Five ideas for growing the Canadian agri-food

INNOVATION: Structure IP agreements and academic incentive models to reward commercialization

Potential impact: Improve universities’ weakening role in innovation and reverse trends in business outsourced investments to universities for agri-food R&D, which have fallen 64% in the past five years.19

Incentivizing commercialization requires exploring approaches beyond rewarding researchers via grants that measure success based on peer-reviewed publications and promotions dependent on traditional academic-research-services model. Agri-food faculties across Canada could consider strengthening their promotion of academic-entrepreneur pathways for researchers—like Dalhousie University’s Agriculture Faculty offers—and create structured opportunities for universities and the private sector to negotiate IP ownership to support commercialization. This could include enabling co-design partnerships among institutions and companies, providing clearer conflict-of-interest guidance, and embedding commercialization activity into promotion and tenure criteria, particularly in applied sciences and engineering disciplines.

It is common practice for Canadian universities and colleges engaged in private-sector projects to automatically own the IP that’s developed. While this approach is often designed to protect public interest and institutional value, these conditions—combined with the lack of formal recognition, tenure credit, and financial reward structures for researchers acting as entrepreneurs—can create material barriers to commercialization. As a result, institutions like universities, which are foundational breeding grounds for experimentation and novel idea generation, risk being increasingly excluded from the agri-food commercialization pipeline, particularly in capital-intensive and applied innovation areas such as food processing, biomanufacturing, and agriculture tech. The U.S, Israel, and parts of Europe have demonstrated that flexible IP ownership models—such as creator-owned or shared-IP frameworks paired with clear revenue-sharing mechanisms—can materially increase startup formation, industry collaboration, and downstream investment without compromising academic integrity.

EARLY: Harnessing AI to steward early growth and engagement through a public-private concierge

Potential impact: Mitigate the stark deal count shrink of 450% from early stage to growth stage; and retain entrepreneurial STEM and business talent in agriculture beyond the current 1% of postgraduates.20

To solve early-stage roadblocks, build an AI-powered concierge platform within an existing national organization with sector credibility and institutional knowledge that allows startups to navigate public and private opportunities in one place, building upon existing tools like AgPal.

There have been previous attempts at building similar services to help startups navigate this landscape, and many incubators and accelerators offer connection and navigation services. Yet, agri-food startups consistently report being lost in the early stages of company formation and experience a sharp drop-off in support once they graduate from an incubator or accelerator. This “support cliff” is particularly acute in agri-food due to long R&D cycles, regulatory complexity, and capital intensity. Such a tool could provide tailored, real-time guidance on funding eligibility, customer discovery, regulatory pathways, clearer hand-offs for each growth capital stage, and ecosystem connections.

Optimizing the platform would require investors and early-stage supporters to align on shared definitions of market segments, innovation categories, and support mandates so the tool can accurately route startups to the right opportunities.

VENTURE: Agri-food experts translate sector complexity into investment logic for the generalist investor

Potential impact: Address agri-food’s underwhelming share of total domestic growth capital by engaging more generalists in the sector, while also attracting a larger share of global venture capital investment, totally more than $500 billion in 2025.21

If the sector wants outsiders to engage, existing agri-food leaders and investors in Canada need to offer more intentional platforms for non-agri-food investors to build familiarity, context, and conviction. A starting point could be targeted national roundtables for each market segment led by select agri-food investment leaders for domestic and international generalist investors to start building connections, share sector-specific investment theses, and compare notes on market segment profiles, timelines, and exit pathways.

On the other side, general investors that have intentions to materially and strategically invest in the sector also have an opportunity to pull agri-food into their coverage area. Opportunities to embed agri-food expertise directly into investment decision-making could include:

-

Investment committees and advisory panels that upgrade their agri-food expertise by including agri-food operators, processors, and sector investors.

-

Fund managers of investment firms participating in federal programs like VCCI must have a team with either:

-

Prior agri-food investing experience, or

-

A formal advisory relationship with sector experts.

-

Venture funds and programs allow for sector-specialist sub-allocations within broader funds such as agri-food market segment carve-outs within generalist funds.

GROWTH: Governments to reorient Canada’s growth, infrastructure, and venture funds to align with the country’s strategic advantages, including agri-food

The potential impact: Position agri-food to have investable projects and companies for government-back funds to invest in beyond the current 2% that the sector captures from these funds.

Although agri-food is cited as one of Canada’s key strategic advantages, government investment programs – at the provincial and federal level – are often not accessible to growing agri-food companies because they are not fit for purpose for the types of innovation, asset intensity, and scaling timelines typical of the sector. This misalignment leaves significant agri-food potential unleveraged.

For example, VCCI does not explicitly exclude agri-food, and some participating fund managers do operate agri-food-focused funds. But only 3% of companies invested in through VCCI-supported funds operate within the agri-food sector. While fund manager expertise and explicit mention of agri-food plays a role, so too do program criteria, technology definitions, and innovation classifications that shape investment decisions and systematically bias capital toward digital-first or asset-light sectors, resulting in agri-food being overlooked.

Rather than creating entirely new programs, existing funds could establish agri-food lanes with tailored tools. One option is to explore a growth-stage agri-food mandate within VCCI or its successor under the $1B Venture and Growth Capital Initiative that was announced in the 2025 federal budget.

There is an opportunity to adjust eligibility rules for federal and provincial government funds to reflect how agri-food companies scale as they raise growth capital, making way for high-quality agri-food companies:

-

Accepting asset-heavy business models that have robust business and risk management plans (e.g., processing facilities, fermentation tanks, cold storage, pilot plants)

-

Recognizing process innovation, novel ingredients, yield improvement, and cost reduction as legitimate innovation—not just software or IP-only advances

-

Allowing longer commercialization timelines (7–10 years vs. 3–5) consistent with regulatory, construction, and market adoption realities.

EXPANSION: Ignite growth in Canada’s agri-food value-add through tools that mitigate revenue uncertainty

Potential impact: Canada is a net exporter of processed and value added agri-food products with immense potential to host more processing of products that are largely still exported as raw ingredients. One example is plant protein: while Canada is the number one exporter of dried peas, roughly 88% of production over the past five years has been exported as a raw commodity.22 23 This one example significant missed opportunity for domestic value creation, job growth, and export diversification to benefit from the burgeoning pea protein industry.

Expanding the Canadian agri-food value chain, requires public and private investors to be deploying blended capital structures that reflect agri-food economics. This includes considering tools to mitigate risks in capital deployment for high-impact projects that address a clear growth opportunity for Canada’s agri-food sector such as:

-

Subordinated or patient capital alongside private equity

-

Government first-loss guarantees to de-risk infrastructure projects

-

Revenue-linked instruments or convertible structures suited to variable margins

-

Support for offtake-linked financing when buyer commitments are conditional but there is clear demand

In agri-food markets, upstream buyers often hesitate to confirm long-term offtake agreements before facilities are built or scaled, while investors require revenue certainty to deploy capital—creating a structural deadlock. Targeted risk-sharing tools can bridge this gap and unlock private investment into processing, ingredients, and food manufacturing capacity. Of course, Canada will need to find buyers for processed verse raw ingredients, but not exploring the opportunities to scale processing domestically is a lost value creation opportunity for Canada.

Download the Report

Authors

Lisa Ashton, Agriculture & Nature Policy Lead

Editorial and production

John Intini, Senior Director, Editorial, RBC Thought Leadership

Yadullah Hussain, Managing Editor, RBC Thought Leadership

Caprice Biasoni, Design Lead, RBC Thought Leadership

Lavanya Kaleeswaran, Director, Digital & Production, RBC Thought Leadership

Alison Suntrum, Nya Ventures and CDL Agri-Food

Amy Standish, Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture

Andrew Heintzman, InvestEco Capital

Arlene Dickinson, District Ventures Capital

Ben Gibbons, Water Point Lane

Bianca Parsons, Alberta Food Processors Association

Blair Knippel, Inside Out LLC.

Brennan Gillis, Dalhousie University

Bruce Rathgeber, Dalhousie University

Celine Hildebrandt, Farm Credit Canada

Chris Hartt, Dalhousie University

Chris Paterson, Tall Grass Ventures

Chris Theal, Phytokana

D’Arcy Hilgartner, RDAR

Dana Gibson, Alberta Innovates

Darren Anderson, Vive Crop Protection

Dave Barrett, Dalhousie University

Dawn Trautman, SVG Ventures, THRIVE

Drew Dwernychuk, Innovation Saskatchewan

Evan Fraser, Arrell Food Institute, University of Guelph

Ghader Manafiazar, Dalhousie University

Glen Price, Venturepark

Graeme Millen, Farm Credit Canada

Graham Markham, New Protein International

Greg McElheran, Export Development Canada

Haibo Niu, Dalhousie University

Heather Bruce, Dalhousie University

Jeff Linner, PFM Capital Inc.

Jeff McKinnon, Four Mile

Jeff Zweig, Fiera Comox

Jodie Parmer, Canada Infrastructure Bank

Jolene MacEachern, Dalhousie University

Kassandra Quayle, Protein Industries Canada

Kee Jim, G.K., K Jim Farms and Feedlot Health Management Services Ltd.

Ken McDougall, McDougall Acres Grainex Inc.

Kirby Sawatzky, Parkland Potato Varieties

Krista Heidebrecht, Sofina Foods

Kristjan Hebert, Hebert Grain Ventures

Kyle Scott, Emmertech

Laurie Dmytryshyn, PIC Investment Group Inc.

Lawerence Hanson, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Leah Perry, Wittington Ventures

Lenore Newman, University of Fraser Valley

Marie Barnes, Invest Alberta

Martin Vanderloo, New Protein International

Marvin Slingerland, MNP

Matt Coutts, Coutts Agro Ltd.

Matt Petrow, Rayhawk Technologies

Miranda Stahn, New Harvest Canada

Oleta LeRush, BASF Canada

Richa Gupta, Canadian Food Innovation Network

Rob Russell, Emmertech

Robert Saik, T1 Technology Corporation

Shaun Vey, Syngenta Canada

Stefanie Colombo, Dalhousie University

Steven Webb, Global Institute of Food Security

Suresh Neethirajan, Dalhousie University

Travis Esau, Dalhousie University

Tyler Groeneveld, Protein Industries Canada

Wayne Arsenault, Avena Foods

Wilson Acton, Tall Grass Ventures

Agri-food is used herein as an umbrella term that is inclusive of agri-inputs, primary agriculture, food supply chains up to retailer, and agriculture and food support services and technology.

All values are in Canadian dollars, unless specified.

Growth capital is used herein to generally describe the various pools of capital growing companies require to go from ideation to a mature company or exiting.

upstream – inputs including agri-tech; midstream – handling and processing; end-stream – CPGs and retailers.

Prime Minister of Canada. Prime Minister Carney outlines Budget 2025 measures to enable $1 trillion in total investments, 2025.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Gross domestic expenditure on R&D by sector of performance and field of R&D

S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Ag Funder. Global AgriFood Investment, 2025.

S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Ag Funder. Global AgriFood Investment, 2025.

S&P Global Market Intelligence.

S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Protein Industries Canada. Three Farmers Foods attracting increased capital from Canadian investors, 2025.

Statistics Canada. Principal statistics for manufacturing industries, by North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). 2025.

Statistics Canada. Flows and stocks of fixed non-residential capital, by industry and type of asset, Canada, provinces and territories, 2025.

Protein Industries Canada. Canadian start-up Phytokana developing new fava-based ingredients, 2025.

Deloitte. The State of Corporate Venture Capital Investment, 2024.

World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Patent Landscape Report: Agrifood, 2024.

Gagnon, M.A. and Bacon, M. Time to improve transparency at Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency, 2023.

Gabbio, S. Data Dive: Can Finland sustain 2024 funding levels and become a true food innovation hub, 2025.

Burwood-Taylor, L. Japan’s maturing agrifoodtech ecosystem takes larger slice of Asia pie, 2025.

U.S.-U.A.E. Business Council. The U.A.E.’s Food Security Vision: Innovation, Investment, and Partnerships, 2025.

Statistics Canada. Business enterprise outsourced research and development expenditures, by industry group based on the North American Industry Classification System, 2025.

Statistics Canada. Occupation by major field of study, 2022.

KPMG. Venture Pulse Report — Global trends, 2025.

Statistics Canada. Estimated areas, yield, production, average farm price and total farm value of principal field crops, 2025.

Statistics Canada and the U.S. Census Bureau. Trade Data, 2025.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.