A new playbook for balancing bigger government with fiscal health

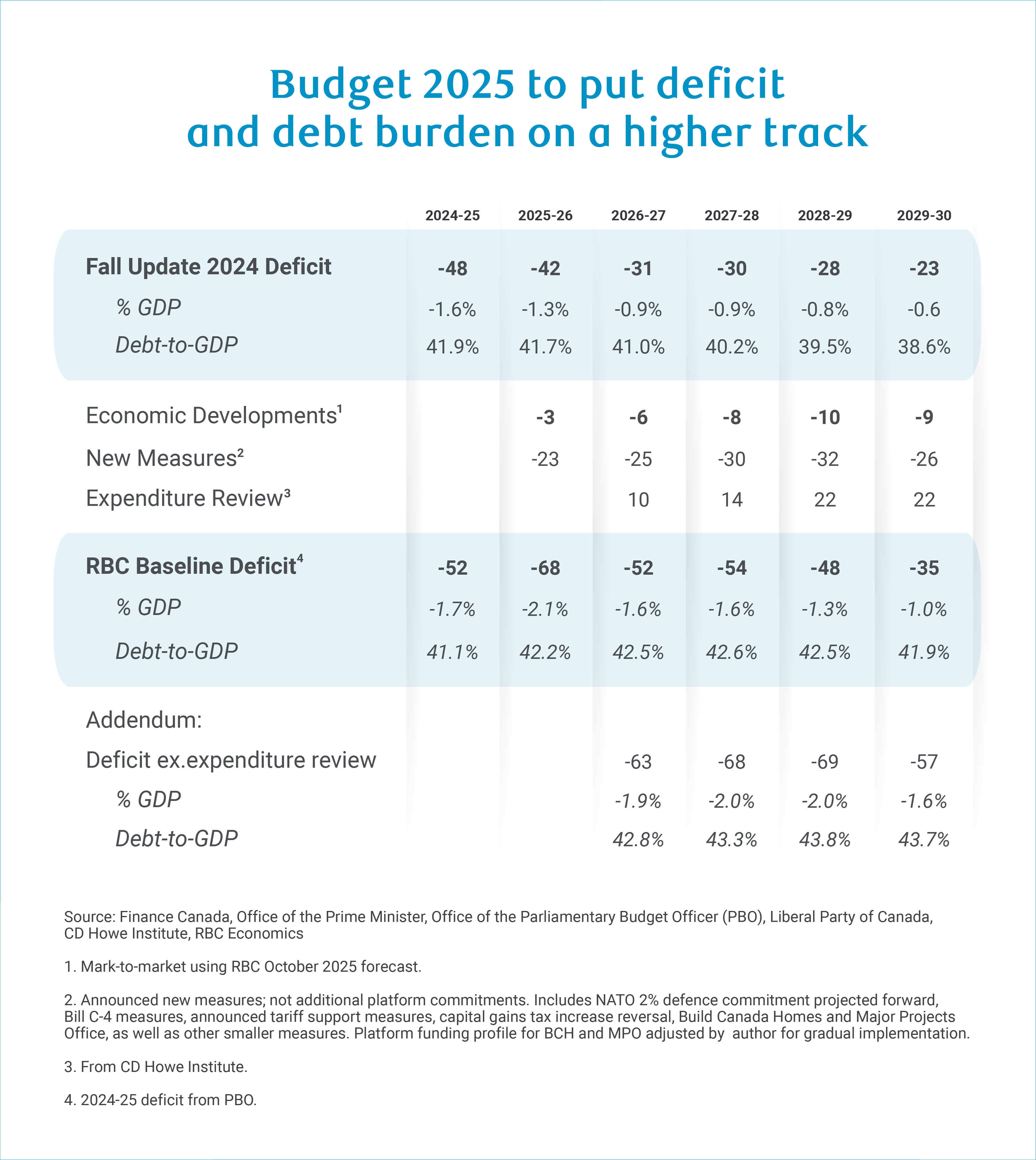

It’s clear the Canadian federal government’s Budget 2025 will see more red ink. We estimate $70 billion this year, five-year deficits averaging 1.5% of gross domestic product (GDP), and debt-to-GDP moving mostly sideways before fiscal pressures.

What’s less clear, but more important, is how this matters for Canada’s economic and fiscal health.

We believe the context and composition of government spending matter as much as the quantum. Cyclically, our outlook has Canada avoiding a recession from the current set of tariffs, but we see localized ones. Meanwhile, structural vulnerabilities of low trend growth and U.S. trade reliance leave Canada exposed to a challenging external environment, yet the business investment needed to change that risks remaining frozen. The Bank of Canada may have additional scope to respond, but pro-growth fiscal policy is the more appropriate intervention.

The government has promised just that with big spending to promote public and private capital formation, while reducing current expenses. Still fiscal space is not unlimited, and any negative shock could limit it further.

Therefore, Budget 2025 has two tasks—deliver a growth-focused agenda and provide sufficient fiscal guardrails to maintain market confidence. In the current environment, these objectives are increasingly linked, requiring a new approach to assess the health of big government.

Two realities

Government will get bigger

Budget 2025 could chart a deficit track more than 60% higher than the 2024 Fall Economic Statement, only avoiding a doubling of red ink thanks to savings from an announced spending review.

In our baseline, the deficit-to-GDP ratio averages 1.5% over the projection period versus 0.9% last fall and would be close to 2% if review savings do not materialize. The debt-to-GDP ratio—a declining trend was the prior government’s fiscal anchor—moves mostly sideways.

Underlying larger deficits is a big context shift. Part of that is the current tariff shock: a weaker economic backdrop and fiscal support for tariff-affected sectors represent more than a quarter of cumulative deficit additions.

But the bulk addresses structural challenges and opportunities—defence, affordability (including housing) and investment that will continue to be sources of fiscal pressure. The feds are also likely to see a greater portion of provinces’ rising health care expenses over time as the country faces peak population aging.

Meanwhile, there are few immediate offsets. Increasing income taxes would make Canada more uncompetitive at a time when investment and talent are needed. More than half of federal spending—transfers to households and provinces—have been scoped out of the expenditure review. Operational savings are partial.

The government will bet on another option. By focusing public spending on investment, a growing economy could generate additional revenues to offset the direct fiscal costs of new spending. However, growth dividends only accrue over time and given high uncertainty, the payoffs of some measures will be unclear. Unless the feds cannot get planned new spending out the door (see last section), this fundamental mismatch will see deficits and debt rise in the near-term.

Debt investors are watching

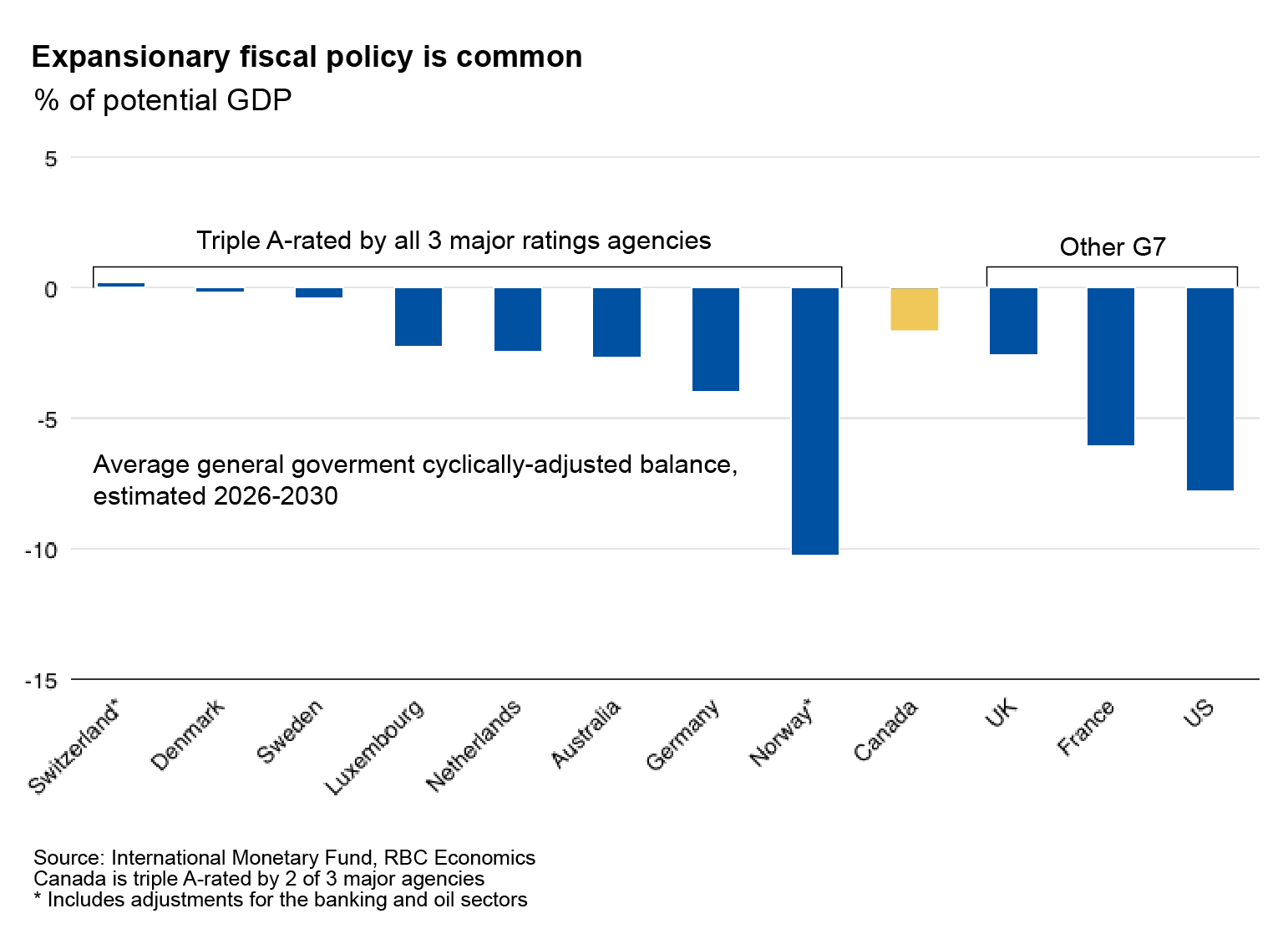

Global markets have been increasingly concerned with rising public debt, focused to varying degrees on France, the U.S., U.K., and Germany, leading to an uptick in long-term yields in some of these economies. Should Canada be concerned?

We’ve highlighted here and here how markets typically prey on the weakest and that Canada stacks up relatively well on fiscal metrics. Gross government debt is high relative to AAA-rated peers, but net debt is much lower and the lowest in the G7. Canada is not alone in having seen high deficits and challenging growth dynamics, and in several ways, has been relatively better off. For example, structural deficits have been lower than many peers.

Still, the math risks turning negative given Canada’s particular exposure to U.S. trade shocks. So, while Canada has fiscal space and markets will likely permit the government fiscal latitude for a growth agenda, investors will be keeping a watchful eye on how the government intends to preserve it for future shocks.

Multidimensional approach to assess fiscal health

A fiscal program solving for long-term growth in an uncertain economy requires a new set of rules and a multidimensional approach—both quantitative and qualitative.

A declining debt-to-GDP ratio, the most recent fiscal anchor of the prior government, will not do, at least not on its own. A successful growth agenda could ultimately lead to a falling debt burden, and thus may be considered the ultimate fiscal objective (and one investors are expected to continue to watch).

Budget 2025 could also show a declining debt-to-GDP ratio in the outer years of the forecast, similar to our baseline.

However, fiscal pressures, the timing mismatch of growth dividends and downside GDP risks suggest it would be a challenge to reliably meet. Unless planned government spending does not materialize (see execution risks below), it would be a rigid anchor.

Instead, the government will focus on elements it can better control—the composition and amount of new spending. The Minister of Finance has confirmed two fiscal anchors (so far), namely, balancing the operating budget within three years and a declining deficit-to-GDP ratio over that period.

There is value in this approach. In crisis moments, markets accept that fiscal policy has to backstop the economy. Other economies with weaker fiscal situations have had latitude to respond in the past. While governments cannot plan for every downside surprise, rigid rules could damage fiscal credibility either ex-ante by being seen as meaningless, or ex-post by needlessly drawing a spotlight to missed (weak) targets.

Still, there are potential weaknesses, and formal rules help with internal discipline. For example, limits are needed on capital spending a declining deficit-to-GDP ratio may not be enough. Capital is eventually consumed, or marginal dollars are not good value for money. Moreover, a capital limit would reduce the ability of governments to reclassify spending opportunistically when operating rules are under pressure.

In the absence of a complete set of formal rules, there is still a path forward. Narrowly defining capital spending, increasing transparency and evaluation, and making some hard choices to build contingencies can inspire confidence. And above all, credibility in the growth story is a huge part of ascertaining fiscal health.

Budget 2025 is about credibility

Budget 2025 must tell both credible growth and fiscal management stories. Still, we don’t expect it to give us a final read on either. The growth orientation of government policy will only unfold with implementation. Given Canada is not the only economy charting appropriate fiscal guidance in an era of big government, it may need to adjust over time. Nonetheless, we’re looking for signals in the following.

The expenditure review is achievable. Balancing the operating budget is only possible under our baseline with review savings, and there is limited buffer in case of other spending pressures. Realizable savings are needed, as well as signals that tough choices can be made.

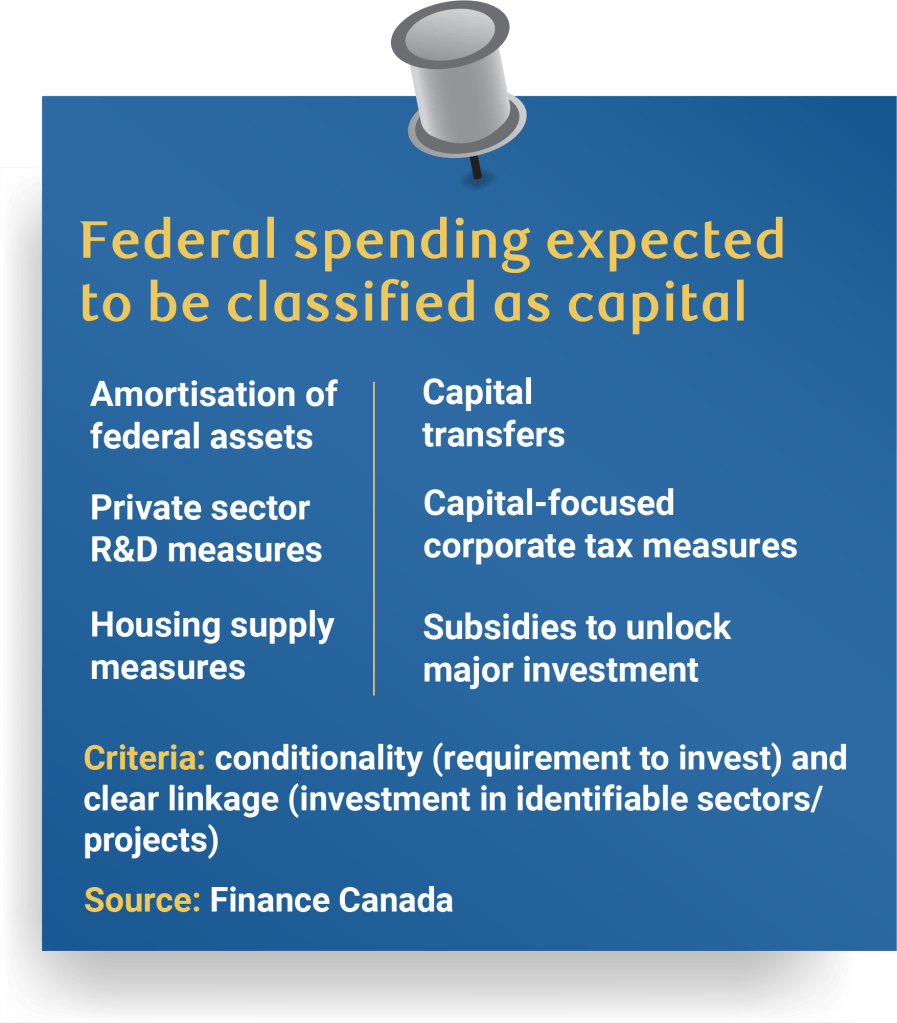

Capital spending is fairly defined: Finance Canada recently provided criteria with six categories of spending expected to conform, but it remains to be seen how broadly it is applied. The Liberal platform said currently capital spending is about 1% of GDP per year and expected to grow under the current government. Our rough estimate gets to 0.8% for 2023-24, but public information is incomplete to be able to assess.

Capital spending is productivity, not just growth enhancing: We have written before about this distinction in the context of greater defence spending. Namely, building defence assets could be stimulative for the economy in the near term but if they subsequently sit idle, the opportunity cost would represent a drag on sustained growth. Investment that enhances productivity such as promoting innovation, connected infrastructure, etc., is more impactful.

Balancing “bold” ambition with “boring” structural policy: Outlines of the government’s agenda has focused on big physical infrastructure (defence, housing, major projects), significant decision-making in the hands of the federal government, and a role for industrial policy. We’re watching how that’s balanced with costless and decentralized approaches like a broad deregulatory or tax competitiveness push. Also, how services, tech adoption, and intangibles— potentially bigger growth engines in the future—figure in plans.

Building contingencies the hard way: Past budgets have incorporated an accounting adjustment for risk. This may have signalling value but does not build fiscal buffers. We prefer scenario analysis to convey uncertainty in the fiscal outlook, paired with actions that gently improve federal finances. Options include tax and additional spending reviews, and addressing open-ended commitments/implicit liabilities, like national pharmacare or provincial health expenses.

Transparency and governance: It will take time to get the new capital framework right. Enhanced details on spending under each of the six categories, as well as a formal “dynamic scoring”1 or evaluation function for an officer of Parliament, like the Parliamentary Budget Officer or the Auditor General, could be valuable.

Execution risk is high but there’s an upside to current growth forecasts

Combining provincial budget 2025 spending forecasts with our estimated federal baseline suggests fiscal impulse could be 3.2% this year and 2.1% next year, on the high end of estimates in our recent analysis.

The numbers are large, but even when Budget 2025 figures are in hand, there will be uncertainty in the total amount and especially timing of new spending. Take-up of tariff-response programs is one factor, as is that half of new measures in our deficit baseline are for infrastructure and defence, which could see delays. Recently created agencies for defence procurement, housing, and major projects support the timing risk.

To date, we’ve conservatively marked up growth forecasts for government spending by 0.1 percentage point in 2025 and 0.3 percentage points in 2026. If federal spending looks like it will be realized at our baseline level, we’ll have to revisit our fiscal add to GDP. There is excess capacity in the economy in the near-term from the current tariff shock to absorb some fiscal stimulus. The longer-term impacts will depend on the level and growth orientation of government spending.

About the Author

Cynthia Leach is Assistant Chief Economist at RBC covering the team’s structural economic and policy analysis. She joined in 2020.

- Dynamic scoring accounts for wider macroeconomic implications in accounting for the cost of new measures. Thus, it would provide an estimate of the growth impacts of new spending, even if there is uncertainty around these estimates. ↩︎

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.