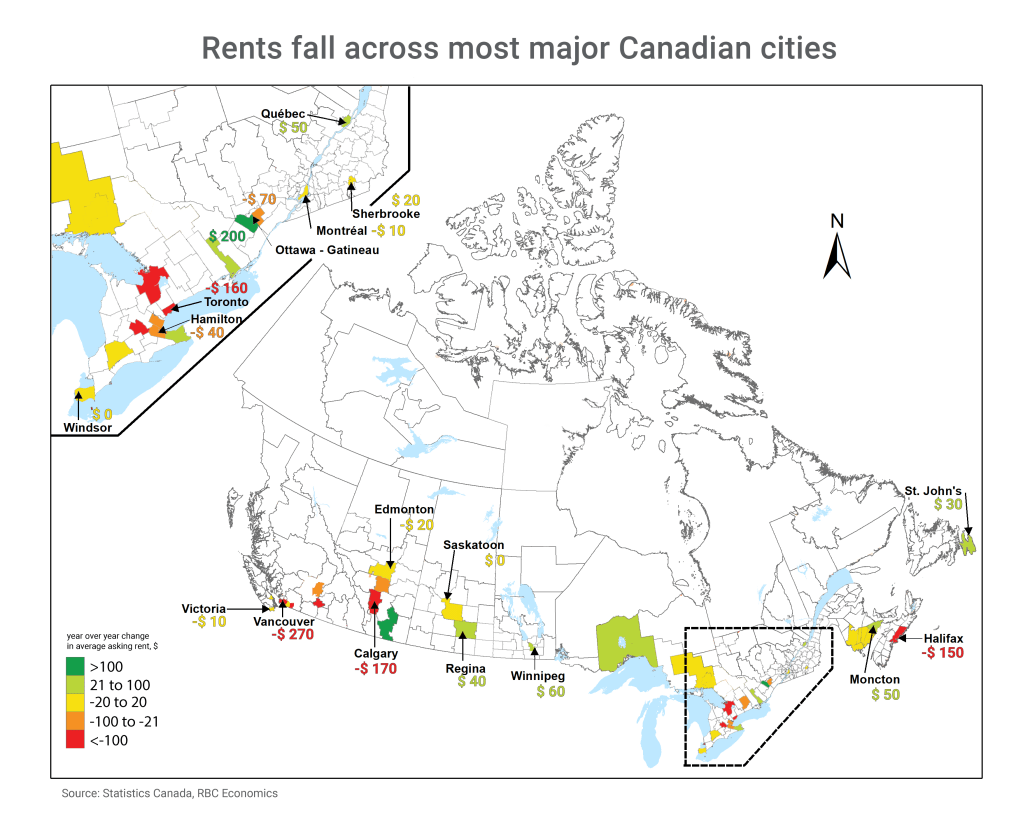

Rents are now declining in more than half of Canada’s 40 Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) from a year ago.

Vancouver leads with the steepest year-over-year drop in Q1 for two-bedroom units (-$270), followed by Kelowna (-$230), Calgary (-$170), Toronto (-$160), and Halifax (-$150).

This marks a notable change from the recovery period after the pandemic when fast growing wages and large inflows of international arrivals supercharged demand for Canadian housing, including rental. In fact, more than a third of Canadian CMAs reported annual rent increases of at least 20% at some point over the last three years.

Market cooling predates Canada-U.S. trade tensions

Softening rents, however, is not an emerging trend in Canada. Our previous analysis highlighted how affordability constraints, decelerating population growth, and increased rental supply have collectively helped rebalance rental market dynamics in recent quarters.

Though we anticipated continued moderation in rents, escalating trade tensions with the United States may be intensifying the trend. We’re now seeing clearer signs of labour market weakness in trade-exposed industries, which may be contributing to the sustained downward pressure on rents.

Weak labour markets and demographic shifts drive rent declines

Rental market softness is especially pronounced in areas where population growth has slowed sharply. Cities in British Columbia and Ontario—historically major destinations for non-permanent residents—have been disproportionately affected by immigration cuts, which has contributed to a sharp slowdown in population growth in these provinces. That’s helped ease housing demand while rental supply continues to build, fostering softer rental market conditions compared to other regions.

Smaller areas are seeing rents slide too—especially those with a high concentration of students. Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo and Guelph, for example, have seen rents fall $130 and $50, respectively, over the last year while London rents have plateaued.

The state of the local job market remains an important factor as well. Most of Canada’s manufacturing and trade hubs (where recent labour market weakness is concentrated) have seen rents decline or flatten from a year ago, including Hamilton (-$40), Peterborough (-$30), Oshawa (-$20), and Windsor ($0).

Ottawa, on the other hand, is a clear outlier with average asking rent up $200 from last year. The city’s large public service workforce—which is relatively insulated from ongoing U.S. trade disruptions—has likely played a role in maintaining rental demand, despite improving ownership affordability and a slowdown in population growth.

Further rent drops ahead

Several factors point to lower rents going forward. Persistent labour market weakness will likely supress wage gains, while stricter immigration targets continue to slow population growth and limit new household formations.

The rental landscape is also being shaped by improving (though still strained) ownership affordability, and lower interest rates—which are easing financing costs for landlords The government’s policy emphasis on expanding rental housing supply should provide additional market stabilization over time, preventing a return to the extreme market conditions seen during the recovery from the pandemic.

But despite these moderating trends, the rental burden remains elevated compared to pre-pandemic levels in all major cities except Toronto. And even there, rents still exceed the recommended 30% threshold for median-income households.

Rachel Battaglia is an economist at RBC. She is a member of the Macro and Regional Analysis Group, providing analysis for the provincial macroeconomic outlook.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.