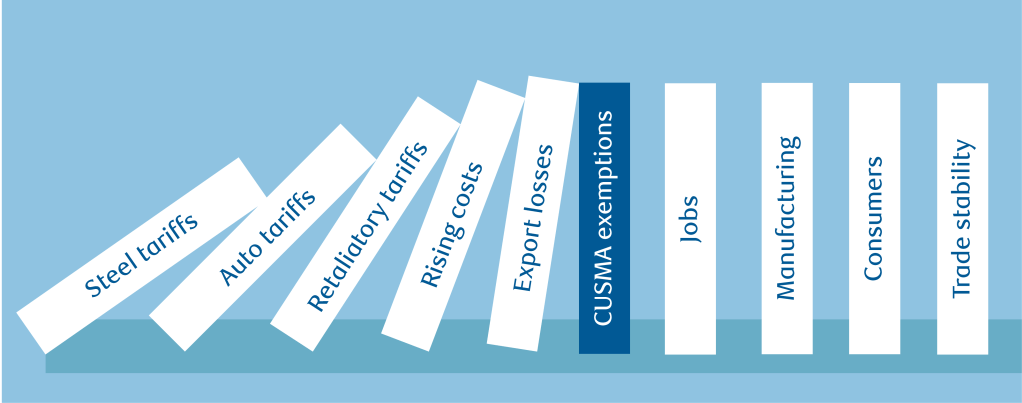

Amid the ongoing trade war, the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) has been a crucial backstop.

While product specific tariffs on goods including steel and aluminum, copper, and non-U.S. content in auto products remain, most Canadian exports have continued to cross the border duty free under a broad exemption from tariffs for trade compliant with CUSMA rules of origin.

Preserving that exemption is critically important for Canadian producers and exporters – and negotiations to extend CUSMA beyond 2036 are scheduled to kick off next year.

While U.S. trade policy remains highly unpredictable, there are good reasons to be hopeful that the CUSMA free-trade agreement could and should remain intact.

CUSMA provides reciprocal duty-free access for the vast majority of U.S. exports

Mirroring U.S. exemptions, Canada as recently as of September 1 dropped its own 25% retaliatory tariffs on all CUSMA compliant goods imports from the U.S.

The CUSMA agreement was designed to be comprehensive and that goes both ways – similar to how it has protected most Canadian exports against U.S. tariffs, it also allows duty free access into the Canadian market for the vast majority of U.S. export products.

There are exceptions, including the Canada’s supply-managed dairy sector. But by our count, at least 95% of U.S. goods exports to Canada1 in 2024 were covered with zero rate duties in the 2020 CUSMA. Of the rest, only 0.3% were explicitly charged with duties, while the remainder mostly fell under Chapter 98 and 99 classifications that cover special trade arrangements and temporary provisions.

U.S. exporters have taken advantage of that access in the past – Canada was the top export market for 32 U.S. states last year.

- This calculation is complicated by the fact international HS product codes have been updated since the 2020 USMCA/CUSMA agreement was signed. By our count, 88% of U.S. exports to Canada in 2024 were in products explicitly listed as duty free under CUSMA, with another 7% accounting for products whose HS codes have changed but are still covered by duty free access. Most of the rest is accounted for goods classified under chapter 99. ↩︎

CUSMA exemption reduces costs for hard-hit U.S. importers

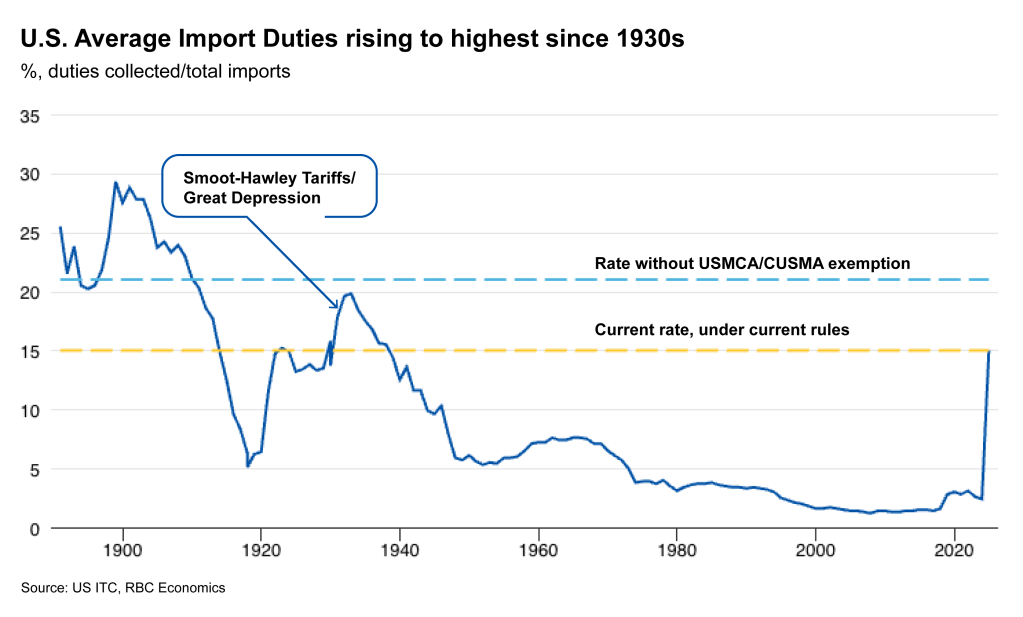

The flip side of extensive duty-free access for Canadian exporters thanks to CUSMA exemptions is also lower tariff bills for U.S. importers, who already have to pay the highest rate of tariffs since the 1930s, but largely on imports from regions other than Canada.

Our calculations suggest the average effective U.S. tariff rate that U.S. importers are facing is on pace to rise to 15% under current rules— a large increase from under 3% last year — but could further rise to above 20% if CUSMA exemptions are eliminated.

Taking the CUSMA exemptions away will also be particularly bad for U.S. manufacturers that are already hard hit by existing measures – the U.S. imports disproportionately more industrial products from Canada and Mexico compared with the rest of the world, and less consumer goods.

Already, manufacturing employment in the U.S. is down 100,000 from a year ago in July. And while the national unemployment rate is unchanged year-over-year, it’s increased by 0.7 percentage points in Michigan, Iowa, and Ohio—states where manufacturing accounts for a high share of GDP. Adding additional tariffs on imports from Canada would make those challenges larger.

Maintaining CUSMA is critical for the trade sensitive U.S. manufacturing sector

The reality is that decades of free trade in North America have left industrial supply chains incredibly tightly integrated across the borders of the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, with intermediate production inputs often crossing borders multiple times at different stages of production before reaching the final assembly line.

While its boosted efficiency, this level of integration also leaves the manufacturing sector at large a lot more vulnerable to intra-continental trade disruptions, compared to tariffs on offshore trade partners.

After accounting for economic integration, we counted nearly 20% of the value of U.S. manufacturing imports from Canada and Mexico actually originates from U.S. exports earlier in the production process. That makes the U.S. its own fourth-largest source of manufacturing imports, according to OECD data.

As a result, imposing tariffs on U.S. manufacturing imports from Canada and Mexico is essentially equivalent to taxing U.S. exporters and will raise costs across the North American manufacturing sector.

Negotiations to extend USMCA/CUSMA are a good thing

U.S. trade policy will likely remain highly unpredictable. But the fact that the CUSMA backstop has broadly held through repeated broader rounds of U.S. tariff announcements should serve as an implicit acknowledgement that all parties see value in the agreement.

A “joint review” of the CUSMA agreement is set to begin in 2026 (and could start earlier than that) but the agreement itself does not automatically expire until 2036. The larger, yet-to-materialize concern — similar to what existed with CUSMA’s predecessor, NAFTA — is that any country can withdraw from the agreement by providing six months’ notice, no negotiations required.

From that perspective, the fact that both U.S. and Canada have worked to preserve the agreement instead of unilaterally withdrawing from it is a good sign, and so are future negotiations that are designed to start a decade ahead of the actual sunset of the agreement to allow ample time to address concerns.

About the Authors

Nathan Janzen is an Assistant Chief Economist, leading the macroeconomic analysis group. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States.

Claire Fan is a Senior Economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic analysis and is responsible for projecting key indicators including GDP, employment and inflation for Canada and the US.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.