The federal government may not have a 2025 budget until the fall, but deficits are likely heading higher from what was expected in the 2024 fall update. Announcements on items like defence along with extensive election promises make the direction clear—even if the exact when and where are not.

Meanwhile, what has often been less appreciated is how provincial government balances play into the government spending outlook. Collectively, provinces are about half of combined federal and provincial government program spending. They represent only a quarter of combined deficits expected for 2024-25, but the overall firm increase in future deficits baked into 2025 provincial budgets make it a story worth paying attention to.

We have conservatively marked up our late 2025 and 2026 gross domestic product forecasts, given the strong expected fiscal impulse.

But fiscal policy will remain a wildcard in the economic outlook. Its impact on growth depends on what types of initiatives move forward, when, and how the overall economy evolves. Here’s how it breaks down.

Fiscal balances have eroded since fall updates even before a 2025 federal budget

The federal and provincial net fiscal balance is expected to erode over the forecast horizon, especially in the 2025-26 year with a peak $37 billion in additional deficit spending versus fall plans under base assumptions (see below). This would raise the combined 2025-26 deficit from $51 billion to $88 billion.

Our analysis includes budget 2025 projections for all provinces but, for comparability, removes the differing contingencies many provinces added in early spring budgets at the height of U.S. tariff threats1. For the feds, base figures include announcements to date2, while potential figures incorporate platform measures. Caution is needed on the latter as it’s common for some platform promises to go unpursued, and the fall budget suggests platform in-year spending could be pushed later as well.

Under base (potential) assumptions for the federal deficit, provinces contribute more than 60% (45%) to projected deficit additions over the next two years, and an average 33% (28%) of the total deficit. In the fall, provinces were expected to represent only 17% of the lower combined deficit. In 2027-28, the combined provincial deficit could be minimal ($4 billion), while the federal deficit could still be in the $50-$60 billion range.

Provincial budgets tend to cover three years ahead, while the feds cover five years, so looking at contributions beyond 2027-28 would give a distorted picture. Moreover, it’s important to keep in mind the trend of recent years – federal deficits have tended to come in higher than previously projected, while on average, provincial deficits have tended to be lower.

Fiscal impulse could be much higher in the future

These deficit figures would lead to a significant increase in the fiscal impulse compared to what was expected in late fall when federal and provincial spending was expected to be 1.6% of GDP in 25-26 and fall to under 1% the next two years.

Now, the combined fiscal balance could approach 3% in 2025-26 under base federal spending and remain around 1.5% the following two years.

Budgets in 2025 saw an eroding fiscal picture for most provinces relative to fall 2024 plans, with sizeable additions to deficits and planned fiscal impulse in 2025/26. While several provinces added more to their deficits this budget round, British Columbia and Quebec expect the largest fiscal impulse, with planned deficits representing 2% of the economy, whereas Saskatchewan’s fiscal policy is neutral. Planned deficit additions are still sizeable for 2026/27, although a bit more limited in size and scope.

These figures exclude various budget contingencies; posted deficit numbers with the contingencies are notably higher in some cases. They also do not include the contributions to fiscal impulse from federal deficit spending, which would add to the figures below.

Infrastructure heavy measures could have stimulative impact

The extent to which a strong fiscal impulse stimulates the economy depends on the economy’s supply/demand balance and the types of spending measures. Put differently, different types of spending carry different fiscal multipliers.

The Bank of Canada and our own estimates of the economy’s negative output gap are somewhat larger late this year and next compared to expectations at the end of 2024—reflecting U.S. tariff policy and trade uncertainty. In this environment, more public spending could be more positive for growth.

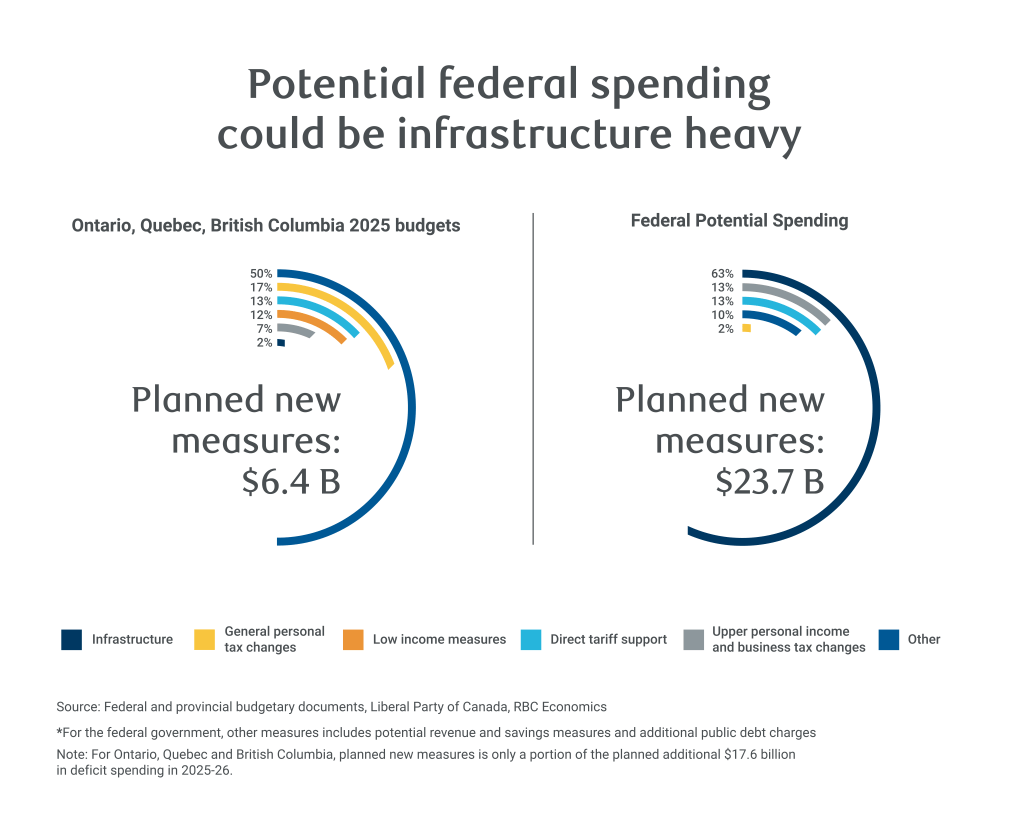

The composition of measures could also be growth positive. Potential federal spending (including platform measures) is weighted strongly to infrastructure. Infrastructure tends to have higher short-term economic multipliers, along with low-income or direct tariff supports, versus corporate or business investment measures, for example3.

Provincial initiatives could also be somewhat supportive. The cost of new measures is not apparent across provincial budgets but is available for the three provinces with the largest government outlays—Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia represent about 75% of provincial government expenditures. In 2025-26, new measures are only about a third of the planned increase in deficits in these provinces and only 2% of these (accrual) costs represent infrastructure. However, there are material additional cash outlays of $4.4 billion the next two years under updated capital plans, covering projects like roads, hospitals and schools.

Fiscal policy to remain a forecasting wildcard

A potentially strong and relatively effective fiscal impulse has led us to conservatively mark up our GDP forecasts by 0.1 percentage point in 2025 and 0.3 percentage points in 2026.

It also contributes to our view that the Bank of Canada is likely done cutting interest rates, given that fiscal policy could take the lead in addressing a weak economy, and is fundamentally better suited to do so.

However, fiscal policy will remain an important wildcard in the forecast. It’s not always clear which measures will be pursued or prioritized with so many demands urgently facing governments, even beyond those promised so far. Getting money “out the door” is another challenge. Infrastructure projects can take a long time to get started, while defence procurement has a longstanding record of delays. The ultimate economic impact depends on what types of initiatives move forward, when, and how the overall economy evolves.

The clear trend of increasing government spending and potentially big effect on the outlook has us watching both federal and provincial government spending closely.

Cynthia Leach is Assistant Chief Economist at RBC covering the team’s structural economic and policy analysis. She joined in 2020.

- It also adds back contributions to the Generations Fund in Quebec (thereby decreasing the deficit) and removes an oil risk adjustment in Newfoundland and Labrador. This analysis does not include how 2024-25 results, updated in some provinces since budgets were tabled, may affect subsequent years. ↩︎

- Included 2% NATO defence target for 2025-26 projected forward, support for Ukraine (assumed no additional fiscal impact), rescinding of the digital services tax, and Bill C-4 income tax cuts. It does not separately incorporate prospective program spending cuts recently requested by Minister of Finance Franu00e7ois-Philippe Champagne of his colleagues (since itu2019s unclear if these are separate from the u2018government operation savingsu2019 in the platform), nor how the deteriorated economic outlook versus assumptions in the 2024 Fall Update, especially in 2026, could affect the deficit. ↩︎

- Although long-term economic effects can differ. ↩︎

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.