Even as the world reels from tariffs, there’s a new levy lurking on international borders: a carbon duty on imports.

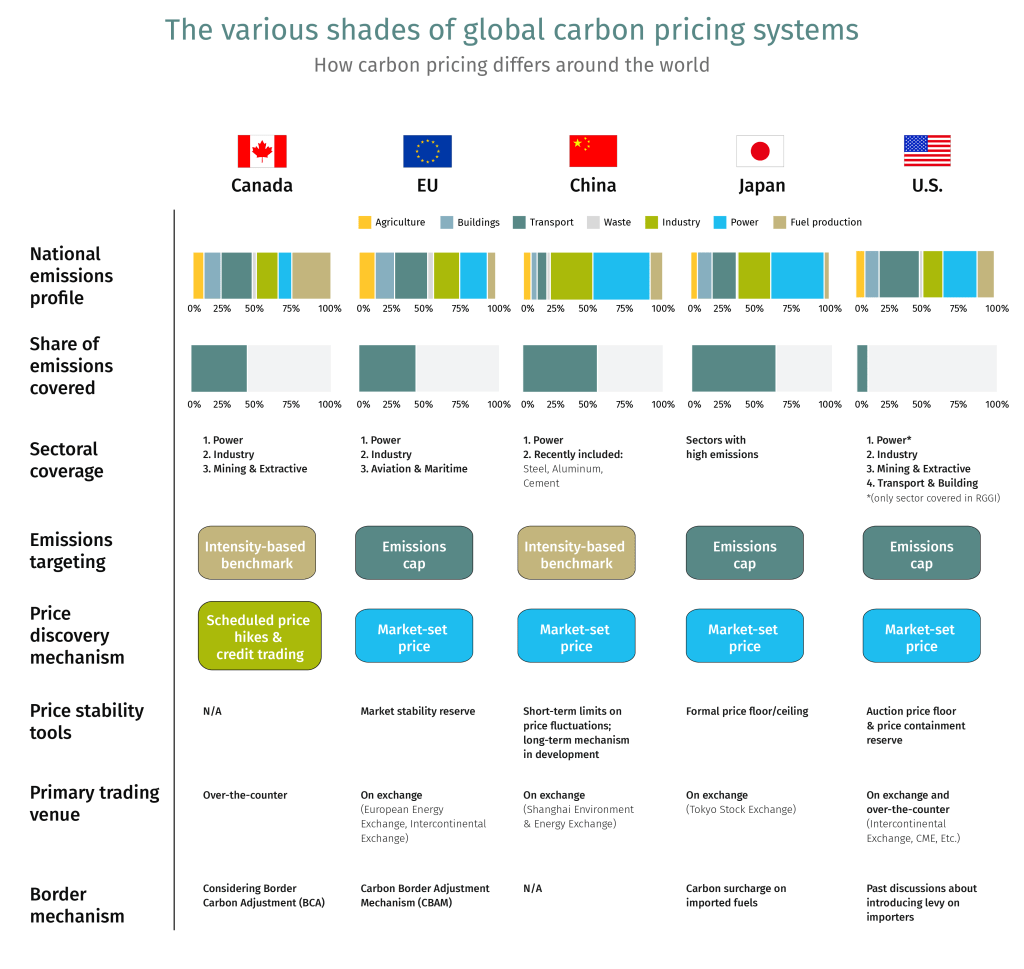

The EU rolled out its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) in 2023; Mark Carney’s government is considering a Border Carbon Adjustments (BCA) to level the playing field for domestic energy and heavy industry against foreign competitors; and a handful of bills in the U.S. at the federal and state level are proposing fees on imports with weaker climate compliance.

The idea of a border carbon fee is simple: ensure that manufacturers from, say, Montreal or Berlin, that spend money and effort to adhere to their domestic robust carbon policies are not disadvantaged against competitors that benefit from weak climate policies in their jurisdictions. Combined, a domestic carbon policy and a border carbon fee is a one-two punch that forces foreign competitors to raise their environmental standards, and ensures domestic industries are not unduly penalized for pursuing decarbonization strategies. Think of Ottawa taxing coal-powered Chinese steel to ensure its not unfairly advantaged against Canadian steel that’s forged by low-carbon but highly capital-intensive electric furnaces.

While a border carbon fee would be a natural extension to Canada’s industrial carbon policy, its implementation is tricky. For starters, it could further inflame Ottawa’s already tense relationship with the Trump administration, which has cracked down on climate policies.

Canada’s carbon policy is in a state of flux, too. Earlier this year, the federal government scrapped a fuel charge—widely known as a carbon tax, followed soon after by British Columbia that had one of the longest and most stable emissions pricing systems globally. The past year has seen Canadian policymakers wobble on industrial carbon pricing: commitment to carbon pricing in Quebec and British Columbia all the while Alberta froze its carbon price at $95/tCO2e earlier in the year, and Saskatchewan cancelled its industrial carbon pricing system.

Canada’s industrial carbon policy has had mixed success to date—it has helped fund renewable energy projects, but with limited direct impact on emissions reduction to date. As the federal government and some provincial jurisdictions look to adjust their industrial carbon pricing strategy, they will also need to factor in shifting trading patterns, changing global economic priorities and the competitiveness of Canada’s industries.

Carbon pricing crosses the border

Canada is one of 40-plus countries that have deployed a version of carbon pricing, covering 28% of global emissions.1 Several are now also exploring or advancing domestic carbon pricing systems in response to the European Union’s CBAM:

-

Emerging markets such as India, Türkiye and Brazil are pursuing domestic carbon pricing mechanisms to ensure their exports comply with EU rules.

-

The U.K. is in the process of linking its carbon market to the EU to streamline its climate policy with the economic bloc.

-

China recently expanded its carbon pricing coverage to include cement, steel and aluminum sector emissions.

-

Japan is consolidating its carbon pricing regimes into a single market as part of its Green Transformation (GX) plan, starting early 2026.

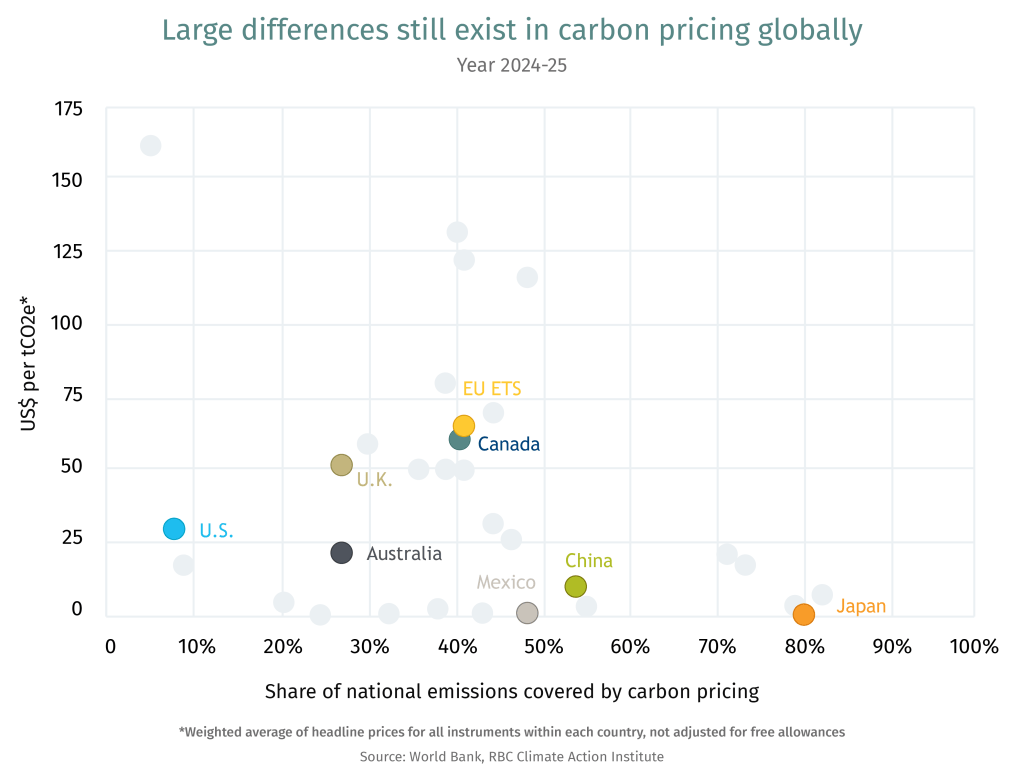

Still, pricing of carbon remains varied. Emissions trading schemes (ETS)—the most common carbon pricing system—rely on market signals to determine the pathway for emissions reduction. As the chart below shows, different jurisdictions assess their sectoral emission profiles, emission reduction potential and costs, that has led to significant differences in how they price carbon.

The U.S.’s Border Carbon Policy Proposals

The Foreign Pollution Fee Act (of 2025) is making its way through the U.S. Senate. It’s a policy designed to impose hefty levies on carbon-intensive imports from primarily China and Russia. But Canada could also get caught in the crossfire, and potentially face carbon tariffs ranging between 17%-33% on its industrial exports to the U.S.2

American policymakers have also been looking to shield domestic industries through a slew of other carbon policy proposals. These include:

-

The FAIR Transition and Competition Act aimed at ensuring American businesses are not undercut by unregulated importers by imposing a border carbon adjustment on carbon-intensive imports.

-

A U.S. Clean Competition Act would establish US$55 per tonne carbon tax on domestic producers and protect them from imports through border adjustments.

-

PROVE IT Act, if enacted, will facilitate the collection of emissions intensity data for energy intensive industries across major trading partners to ensure global transparency on carbon emissions. It was considered a precursor to the Foreign Pollution Fee Act.

The Foreign Pollution Fee Act, reintroduced on April 8, 2025, by Republican Senators Bill Cassidy and Lindsey Graham, seems most advanced. The structure avoids domestic carbon tax, and creates a linear relationship between the levy on importers and their emissions intensity gap. While the bill is unlikely to proceed, it’s seen as another form of protectionism under the guise of climate change policies.

Canada’s carbon pricing patchwork

Alberta and Quebec kicked off Canda’s carbon pricing journey in 2007, pursuing two different ways to apply carbon levies on their large industrial emitters. Now, a patchwork of federal and provincial carbon pricing regimes in Canada apply to a range of sectors including power, industry, mining and extraction, and covering nearly half of the country’s total emissions.

With some exceptions, the emissions trading system is Canada’s preferred carbon pricing mechanism. This is how it works: a greenhouse gas emissions performance benchmark places allowance limits on a company’s emissions. Companies emitting beyond those benchmarks buy permits from other companies with emissions that are under the prescribed level. The policy is designed to incentivize investments in low-carbon technologies that would help sharpen Canada’s competitive edge.

The system has encouraged capital to flow to sustainable projects: More than $80 billion worth of projects in carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS), wind, solar and bioenergy were either shovel-ready or under consideration and poised to benefit from carbon credit revenues, according to the Major Projects Inventory in 2024.3 Similarly, Emissions Reduction Alberta, funded through the province’s industrial carbon pricing, has facilitated over 300 clean technology projects, valued at more than $10 billion.4

Setting performance benchmarks means not all emissions are subject to carbon pricing, only those beyond the allowance limit—by design. Average cost in Canada, when adjusted for free pollution allowances, stood at $10 per tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) in 2024, a fraction of the $80 headline carbon price, according to latest estimate by the Canadian Climate Institute.5 This helps limit carbon leakage (i.e., manufacturers moving to jurisdictions with lower compliance).

Impact on emissions reduction

Carbon pricing reduces emissions with limited or no impact on the economy, according to several studies. But the scale of emissions reduction remains relatively small, with up to 2% annual GHG reduction on average across a range of countries with carbon pricing, including Canada.6 Emissions will need to climb down 6% annually for Canada to reach its climate goals by 2030, as set out in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) commitment to the United Nations.

But there’s a reason the impact on emissions has been muted over the past two decades: Carbon prices were kept low as most clean technologies were nascent with high costs and in early-adoption stage. That’s slowly changing, with solar and wind becoming competitive with fossil fuels, and electric vehicles poised for price parity with conventionally-powered cars; in places like China, EVs are cheaper than gas-powered vehicles. Meanwhile, carbon-capture capacity has doubled globally over the past 10 years.

What’s at stake?

Major discrepancies in carbon pricing with its trading partners can impact Canada’s competitiveness at a time of a structural global upheaval.

Overall, about a fifth of Canada’s imports and exports are from jurisdictions that don’t price carbon. In the U.S.—where policy vary by state—the average carbon price is only US$6 per tonne when adjusted for Canada-U.S. trade flows at the state level.

Here’s what Canada should watch for as its looks to maintain its global competitiveness amid fragmented trade and climate policies:

-

Diversify trade partners: This won’t be an easy task with 75% of goods destined for the U.S. But nearly a third of Canadian export categories are more diversified; even oil and gas exports are finding new customers in Asia since the expansion of the TMX pipeline and the start of LNG Canada. Beyond the U.S., the global rise of climate-compliant products could give Canada an edge. For instance, Japan’s evolving carbon pricing policy favours cleaner fuel sources.

-

Foster predictable policy: Access to capital was the top challenge businesses faced in their emissions reduction goals, as noted in our Climate Action Report 2025. Large-scale investments to advance low-carbon technologies require strong and stable price signals to lower risk and allow capital to flow. Policy certainty could help pave the way for capital to be directed towards Canada.

-

Streamline provincial systems: Reducing barriers and inefficiencies could help de-risk the investment environment. Businesses operating in multiple jurisdictions face different rules, varying price levels and limited or no ability to transfer credits between their facilities. We have previously emphasized that harmonizing fragmented markets could offer considerable economic upside. Removing interprovincial trade barriers could offer greater market access and liquidity.

-

Beware the wrath of the U.S.: Reconciling carbon policy differences with the U.S.— where less than a tenth of total emissions are priced and at a much lower rate—is eventually required. With 80% of Canada’s oil production, 90% of aluminum, about half of steel and a third of cement shipped to the U.S., Ottawa needs to be mindful of how the U.S. reacts to changes to our policies. For some industries like the oilsands, compliance with emissions obligations costs about $1 per barrel, and less than 50 cents when using carbon offsets. This limits the competitiveness concerns. However, other industries already under tariff pressure and commanding much lower profit margins might require more support.

-

U.S. trade irritants cut both ways: Extending carbon pricing to imports through BCA is effectively a tariff. With Canada already at odds with its biggest trading partner, any attempt to level the playing field with American companies might be viewed as a trade escalation.

-

Resolve administrative complexity: From reporting to verifying, BCA is a daunting administrative task. Especially with varying provincial prices, coverage and benchmarks. It’s another reason to pursue harmonization as we wrote previously. The EU excluded SMEs and individual importers from CBAM to avoid regulatory complexity and reduce their costs. Canada should also strive for simplicity of rules.

-

Beware of unintended consequences: Emissions-intensive trade-exposed (EITE) sectors account for only 5% of Canadian GDP. However, those materials feed into an array of downstream industries. In effect, BCA could cascade through the supply chains. Raising costs for imported steel, for example, while protecting domestic manufacturing may raise costs for automakers, and construction companies, among others, as estimated by the Bank of Canada.7

Lead Author

Farhad Panahov, Economist

Editor

Yadullah Hussain, Managing Editor

Summary conclusion based on review of academic literature

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.