The decision of the Supreme Court of the United States on February 20, 2026 to strike down the U.S. administration’s use of the International Economic Emergency Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose sweeping tariffs represents a significant challenge to the government’s trade policies, and raises immediate questions about refund obligations, potential Congressional action, and alternative tools for enforcing tariffs.

All of these are unknown at the time of writing as the ruling invalidates the legal foundation for duties that had collected more than $130 billion to date.

Importantly, this decision could have near-term consequences for inflation’s path in 2026—the extent will depend on how the administration responds in the weeks ahead.

The Supreme Court decision may appear to be a major blow to the administration’s tariff policies, but its trade agenda can be pursued through other avenues.

IEEPA was used as the basis for a majority of Liberation Day tariffs, but other acts have been used by this government (and others) to impose tariffs on US imports.

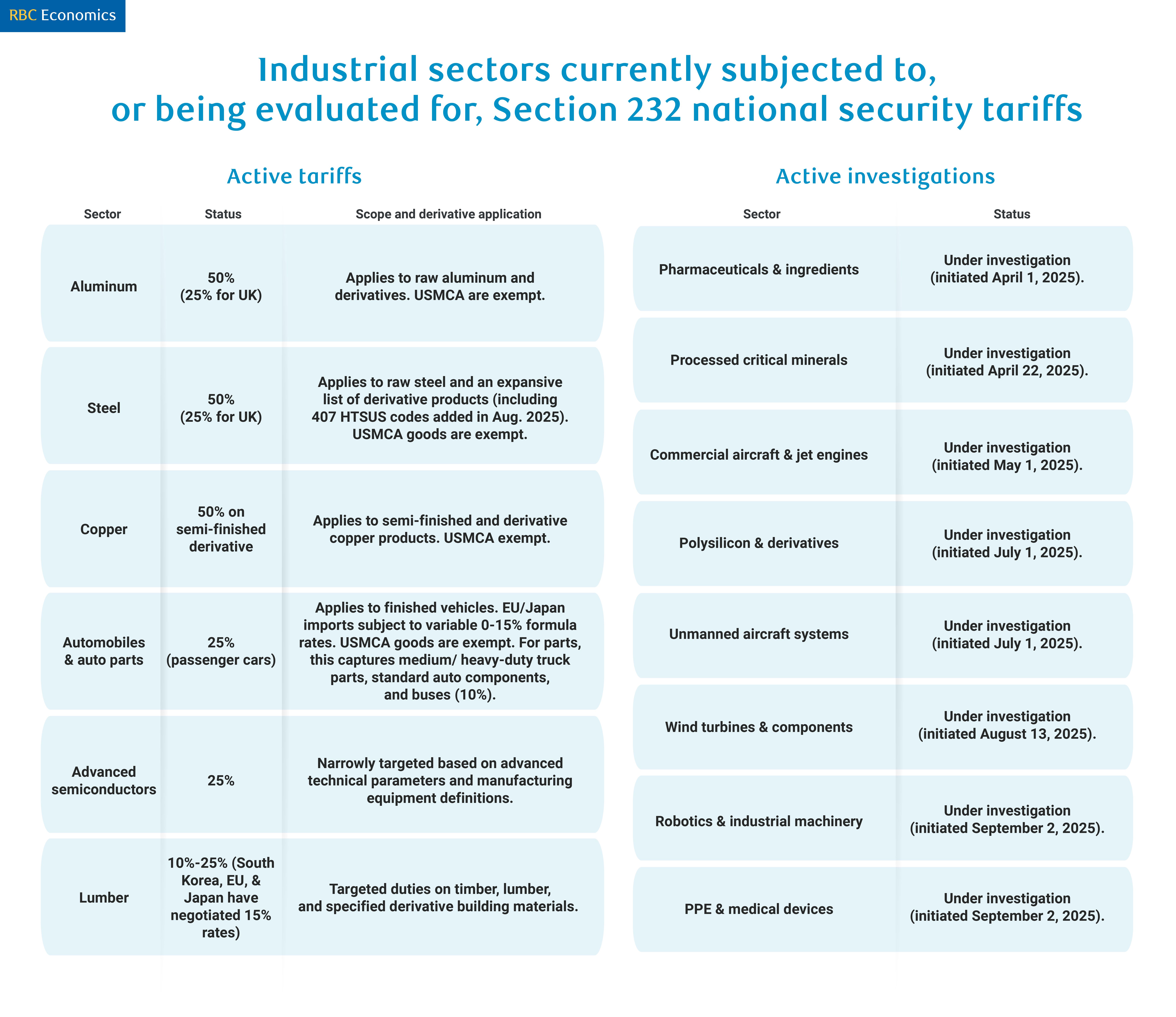

For example, tariffs enacted under Section 232—which targets products based on national security grounds—remain in place, and the administration could use this as a roadmap to cover additional sectors. The downside to Section 232 is it limits the ability of the administration to focus on country-specific trade imbalances.

There is also a risk to existing trade agreements that offer carve outs for existing Section 232 tariffs, and could put greater focus on the USMCA review in July.

Still, the administration has completed or started the necessary studies to invoke additional tariffs under Section 232 for the following sectors:

There are other ways in which the administration could apply new tariffs, which we have outlined below.

Please keep in mind that as economists, we are not in the business of interpreting legal frameworks. In what follows, we have done are best at interpreting historic trade legislation, and these appear to be the administration’s most likely options:

-

Section 122 (Trade Act of 1974) – Balance-of-payments authority: Emergency power for economic crises (includes large trade deficits, currency crises, capital flight, unsustainable foreign debt, etc.). It allows temporary tariffs up to 15% for 150 days to address payment imbalances, but requires specific economic triggers and congressional extension beyond the 150-day limit.

-

Section 201 (Trade Act of 1974) – Safeguards: Actions designed to provide temporary relief for a U.S. industry (for example, additional tariffs or quotas on imports) in order to facilitate positive adjustment of the industry to import competition. The law enables the industry to compete with imports with a “positive” adjustment safeguard measure.

-

Section 232 (Trade Expansion Act of 1962) – National security authority: Allows unlimited tariffs on imports threatening “national security” (broadly defined). It requires a U.S. Department of Commerce investigation (270 days), but has no time limits on tariffs once imposed. It has been used for steel and aluminum tariffs (and could be expanded to include additional industries).

-

Section 301 (Trade Act of 1974) – Unfair trade practices authority: Allows US trade Representative to impose unlimited tariffs against countries with unfair trade practices. It requires investigation (up to 12-18 months). Tariffs expire after four years unless renewed, and is subject to court review as agency action (this section has the most established court review standards).

-

Section 338 (Trade Act of 1930) – Discrimination authority: The oldest and most flexible authority, it allows tariffs up to 50% or complete import bans against countries discriminating against US commerce. It has no time limits or procedural hurdles and minimal oversight requirements.

Zooming out, this ruling has limited impact on our bigger picture perspectives on tariffs as cited below:

-

Average effective tariffs for the US have fallen considerably from levels announced on Liberation Day from more than 30% to roughly 11% ahead of the Supreme Court ruling. “Peak” in tariffs is, thus, likely behind us in 2025.

-

Similarly, collected tariff revenue appears to have peaked (Issue in Focus).

-

We continue to believe tariffs are impacting the economy through moderately higher goods inflation, which will peak in Q2, and through job weakness in trade exposed sectors such as manufacturing, wholesale, retail, transportation and warehousing. These are not significant in impact on an aggregate scale, but are slowing job creation and weighing on the wrong side of inflation in a way that shouldn’t be overlooked.

About the Authors

Mike Reid is Head of U.S. Economics at RBC. He is responsible for generating RBC’s U.S. economic outlook, providing commentary on macro indicators, and producing written analysis around the economic backdrop.

Carrie Freestone is a Senior US Economist at RBC Capital Markets. Carrie is responsible for projecting key US indicators including GDP, employment, consumer spending and inflation for the US. She also contributes to commentary surrounding the US economic backdrop which she delivers to clients through publications, presentations, and the media.

Imri Haggin is an Economist at RBC Capital Markets, where he focuses on thematic research. His prior work has centered on consumer credit dynamics and treasury modeling, with an emphasis on leveraging data to understand behavior.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.