Overall, the story of Budget 2025 is as expected.

There is big new spending and deficits that would be even larger without review savings. Buffers are slim against the two fiscal anchors of a balanced operating budget by 2028-29, and a declining deficit-to-GDP ratio. The debt burden goes up, and then sideways until at least the mid-2030s.

But if new capital-focused spending successfully crowds in the hoped for $500 billion in private investment, the growth dividends could lead to a different outcome of plentiful buffers, and a declining debt ratio. Thus, focus must turn to implementation, and hope for a stable external environment.

Budget 2025 provided more details for each of these elements, but still leaves much to clarify. With lofty expectations and short timelines, this was also expected, although the document could have gone further in a few areas.

The new overarching fiscal objective of $500 billion in private investment implies it would override fiscal anchors, yet it’s not clear how this would be measured. Unsaid is how much of new defence-aligned spending will put Canada on track to meet its NATO 2035 target.

There is also room for interpretation on whether the budget lives up to the government’s billing of transformational change, and pivot to capital-focused spending.

Operating savings are large given the narrow review base even though they’re lower-than-expected, and a portion is still unallocated. Under the government’s definitions, the deficit can be entirely attributed to capital spending by 2028-29. At the same time, new capital spending introduced in the budget is only 36% of the accrual cost of total new spending, meaning new operating spending totals $12 billion per year on average.

Our preview piece highlighted how Budget 2025 would not give us a final read on either the government’s growth or fiscal management agendas. That’s especially true for an evening attempting to digest a big, complex budget. But even once Budget 2025 is fully understood, what comes next will be just as important – the government will need to formalize its new framework and execute on implementation.

Deficit and Debt

Sharp increase in the deficit

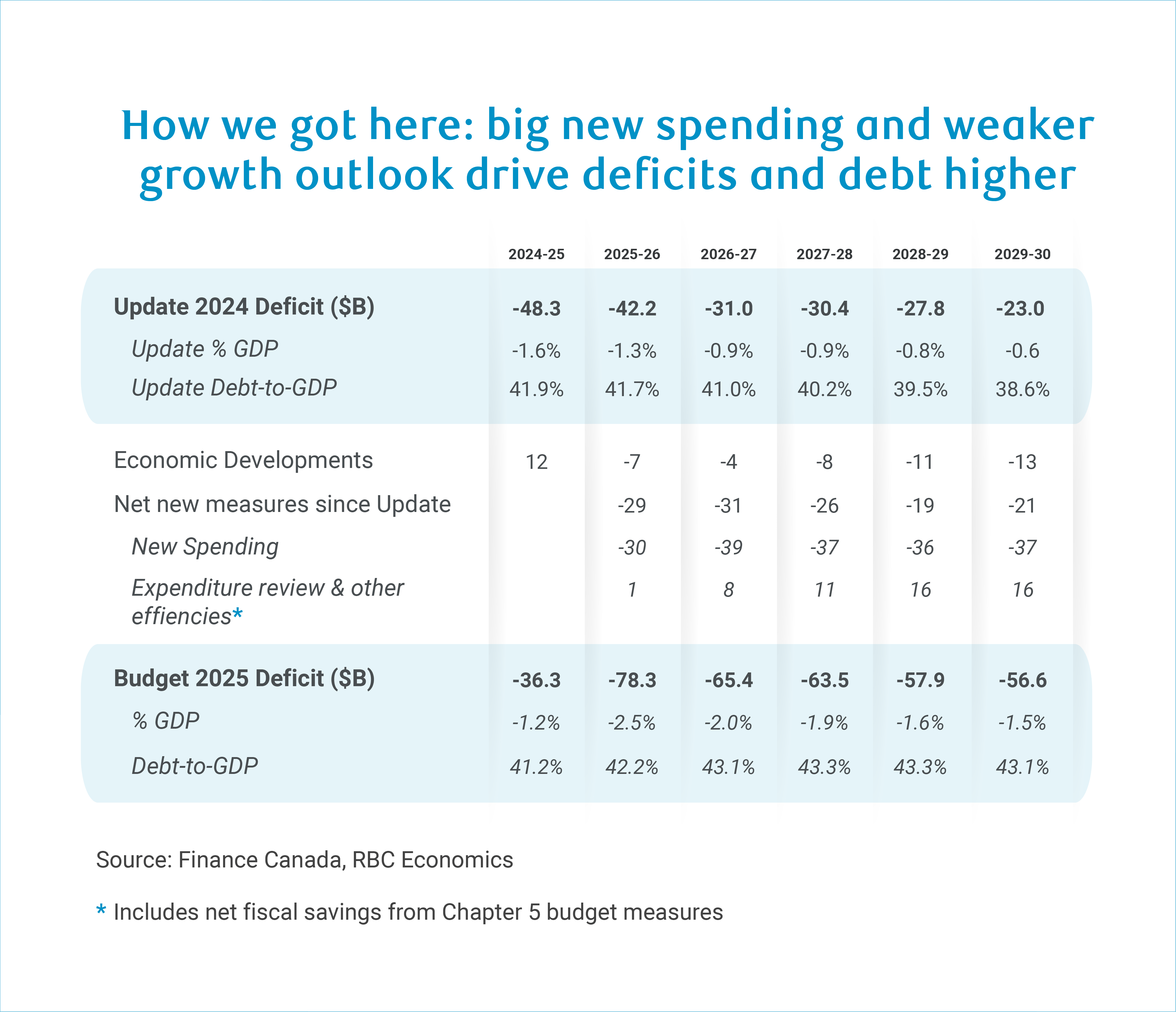

As billed, Budget 2025 is big on new spending. It’s also big on deficit, showing a hefty $78 billion expected gap (-2.5% of GDP) this fiscal year—more than $36 billion (or 86%) above the previous projection.

The government expects the deficit to gradually fall through the remainder of the fiscal plan to $57 billion by 2029-30 (-1.5% of GDP).

This would meet one of the two stated fiscal objectives—maintaining a declining deficit to GDP ratio.

The fiscal picture was better than previously thought going into this fiscal year with the actual deficit for 2024-25 coming in at $36 billion, markedly lower than the $48 billion shortfall projected in the 2024 Fall Economic Statement.

A weaker expected growth profile adds to the red ink versus FES 2024 to the tune of $42 billion over the horizon, but is eclipsed by net new spending of $126 billion.

New spending in this fiscal plan is actually $178 billion, but is partially offset by savings. Without those expenditure review and efficiency savings, the deficit would remain in the $70 billion range throughout the forecast period.

Indebtedness no longer easing over fiscal plan

The federal government’s net debt burden—a declining ratio was the prior governments’ most recent fiscal anchor—is set to increase to a peak of 43.3% in 2027-28 and 2028-29 before inching barely downward in 2029-30.

The debt burden is no longer a fiscal anchor (more below). But, the government has provided very long term projections showing a declining ratio (under a reasonable set of economic assumptions) expected to turn downward by the mid-2030s.

This projection does not include any upside from growth investments or fiscal pressures. See below.

A new framework: Capital vs. operating budgets

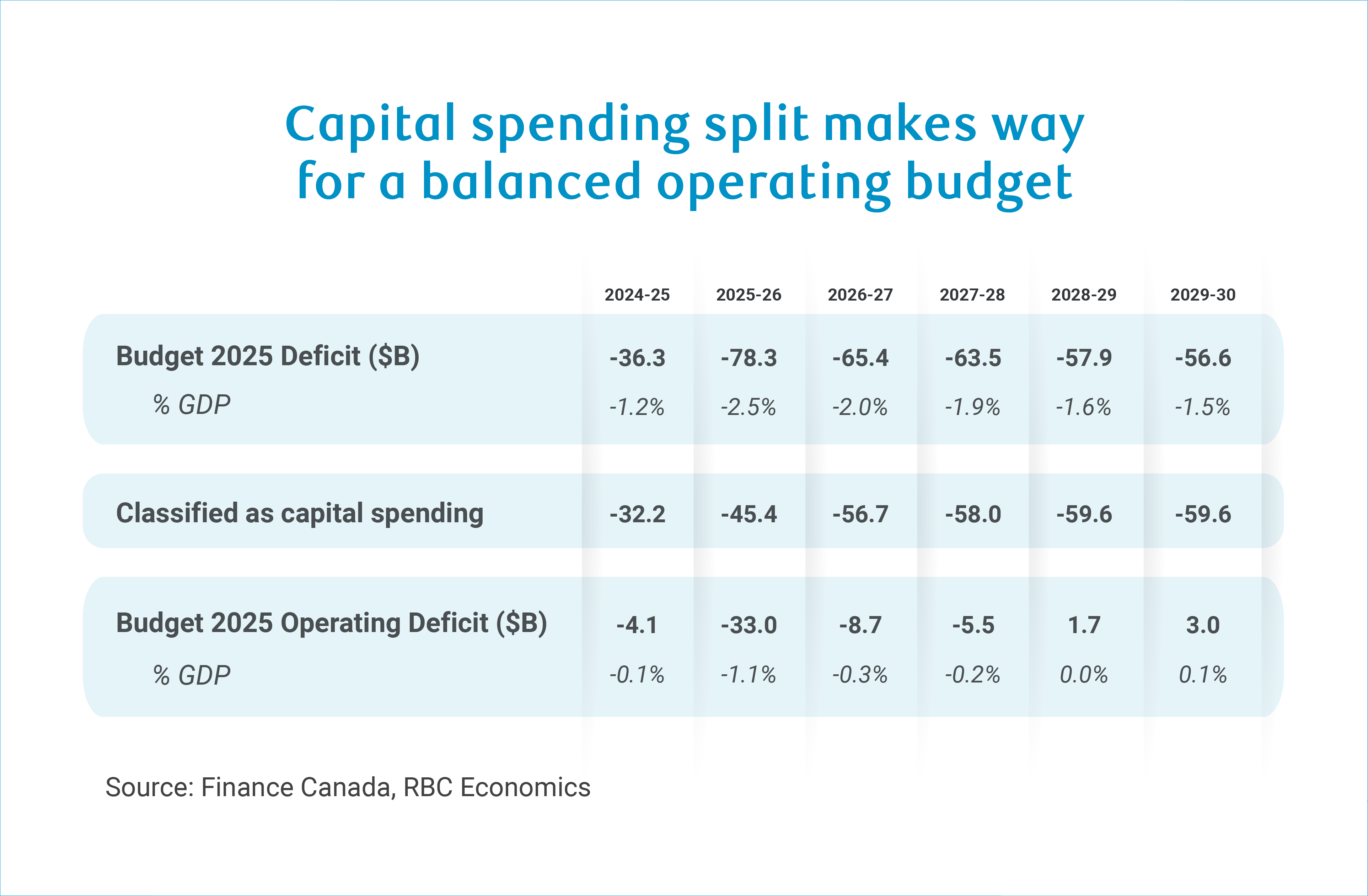

Capital spending reclassification paves to way to balancing the operating budget

Spending reclassified as capital ranges from 1.4% to 1.7% of GDP from 2025-26 on. This leads to the operating budget balance improving to -0.3% of GDP next year and becoming positive from 2028-29, meeting the other stated fiscal anchor of balancing the operating balance within three years.

The budget noted that in recent history, capital spending’s share of GDP has been about 1%, and was projected to grow to 1.4% over the forecast horizon based on existing measures. Budget 2025 lifts that trajectory to about 1.7% of GDP by the outer years of the forecast period. This increase is attributed mainly to four major initiatives—Build Communities Strong Fund, Productivity Super Deduction, Build Canada Homes, and the Defence Industrial Strategy.

The total increase in investment spending over the five years is $32.5 billion, representing 36% of net new spending over five years specifically from Budget 2025 (as opposed to $126 billion since the Update). This means the Budget still has a decent amount of non-capital new spending of about $12 billion per year.

Some ambiguity remains

It will take time to digest the boundaries and relevance of the new capital definitions for both growth and fiscal health.

The budget helpfully provides a line-by-line accounting of baseline and new measures under each of its six capital categories. But, there is still some ambiguity in how criteria of conditionality (requirement to invest) and clear linkage (investment in identifiable sectors or projects) apply.

Budget 2025 also provides a comparison of capital definitions across UK and Singapore that adopt a similar approach. On the surface, it implies a more expansive definition being applied in Canada, given the inclusion of corporate income tax credits and corporate operating subsidies for committed new investments. It’s unclear on federal assets. Canada will count the currently consumed portion of capital (i.e., amortization which grows strongly with growing defence spending) under its capital spending, while the UK seems to account for the whole acquisition cost.

We’ll do more work in this area, but expect the PBO’s opinion would carry weight with Canadians and investors. We’d expect them to do so in the coming weeks. What we did not see in the budget is the enhanced role for the PBO mentioned in the Liberal platform .

Fiscal rules and buffers

New fiscal anchors and guidance

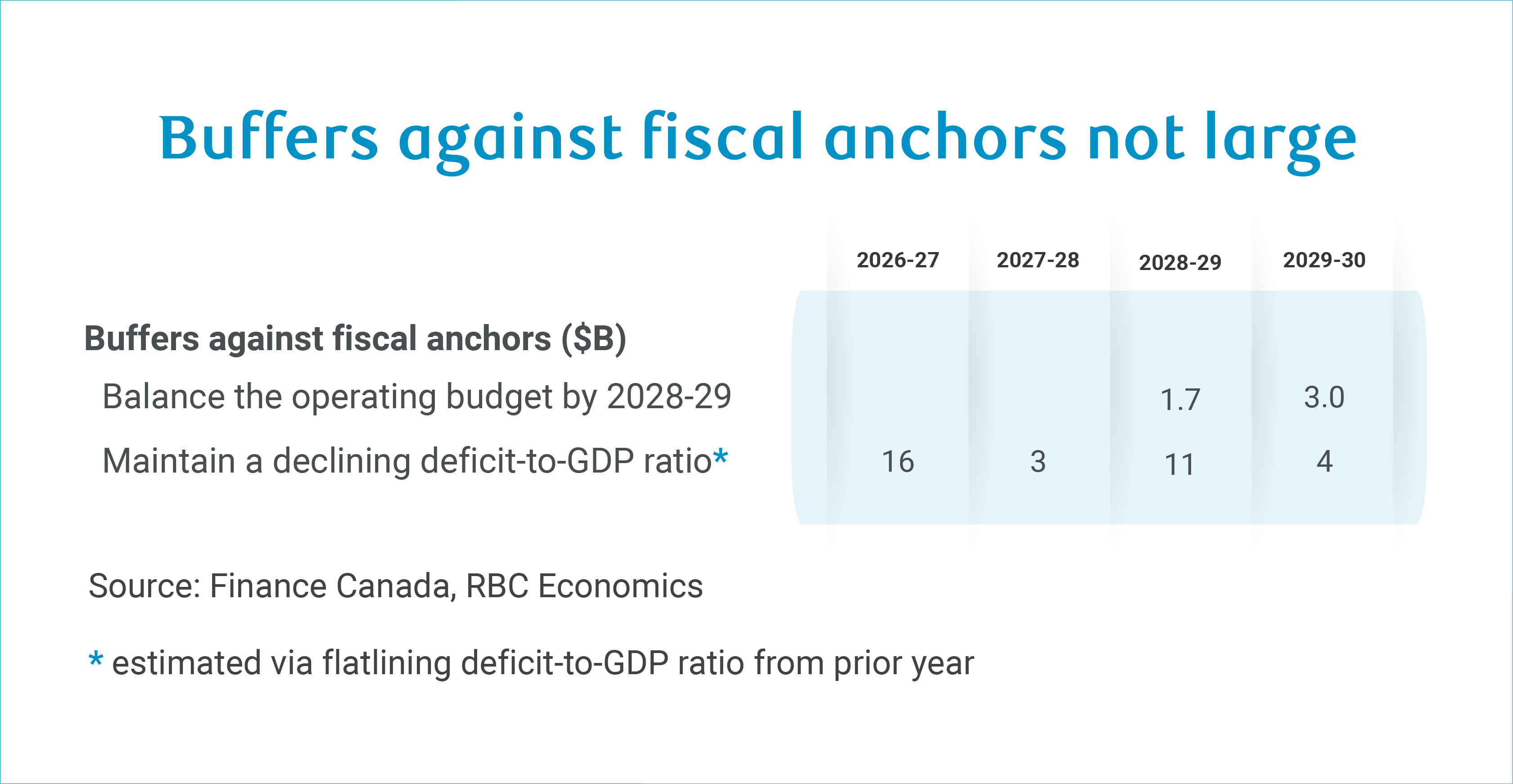

Budget 2025 limits the government’s fiscal anchors to the two previously announced: a declining deficit-to-GDP ratio and balancing the operating budget by 2028-29.

It also introduces an “overarching target” or fiscal objective in catalyzing $500 billion in new private investment over five years.

The government has the least amount of buffer to meet its operating balance anchor with only $1.7 billion and $3 billion to the positive in the last two years of the forecast period with full expenditure review and efficiency savings achieved. Its moderate downside scenario (see below) would deduct about $9.2 billion annually from the bottom line, most of which would likely fall on the operating balance. The declining deficit-to GDP ratio fares a little better with about a $16 billion buffer in 2026-27.

The Budget estimates (on a cash basis) that $280 billion in federal capital investment has the potential to crowd in other public capital, and $500 billion in new private investment for a total $1 trillion in new capital spending. If realized, the government estimates it could increase GDP by 3.5% by 2030, improving the fiscal balance by $7 billion per year and providing more room to maneuver. The debt burden would also start trending down almost immediately.

Importantly, the Budget’s clarification of the ultimate target of $500 billion in new private investment implies fiscal anchors are subject to change if this is not met. Yet Budget 2025 does not provide details on how to the government intends to define this metric so Canadians and investors can track its progress.

Economic assumptions reflect challenges Canada is facing

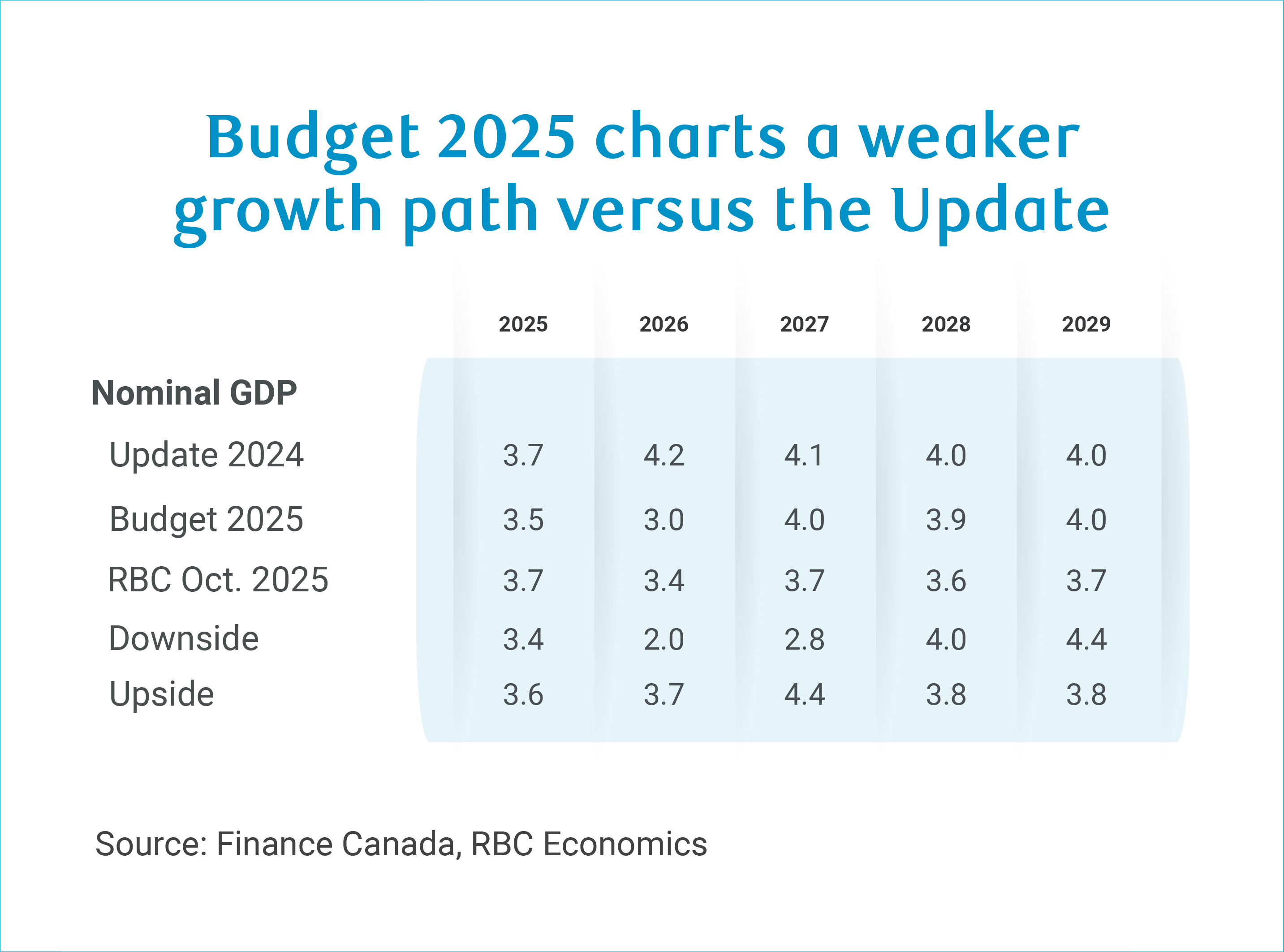

Budget 2025 charts a moderately weaker path for nominal GDP versus FES 2024, especially in 2026. The Budget’s growth assumption is also slightly weaker in 2025 and 2026 than RBC’s most recent forecast, but slightly stronger in the outer years.

The Budget contains both downside and upside growth scenarios—relatively moderate shocks that mostly affect the earlier years of the forecast period. While the downside scenario would deduct $9.2 billion annually from the bottom line, on average, the upside scenario would add about $5 billion per year. Under both alternate scenarios, the federal debt-to-GDP ratio would still trend down over the longer term (pre any growth dividends), but very slightly under the downside.

Details of New Measures

Expenditure review and new revenues

-

Government savings initiatives are expected to deliver $56 billion in savings over five years, lower than expected, but unsurprising given the scale and pace of the exercise.

-

Comprehensive Expenditure Review savings are set to deliver $44 billion over five years, versus the $68 billion we penciled into our baseline, already lower than some other forecasters. With more detailed information provided for each federal department, it will take time to determine how tangible some of these savings are.

-

The balance is largely made up of $4 billion in CRA initiatives and a commitment to find another almost $8 billion by optimizing productivity in government.

-

Public service downsizing by 40,000 positions (10%) from the 2023-24 peak to reach approximately 330,000 by 2028-29. Workforce renewal strategy offering voluntary early retirement incentives to manage public service reductions while protecting diversity and ensuring a strong younger generation of public servants.

Defence gets a big boost in spending

New spending dedicated to “Defending our Sovereignty” totals $59 billion over five years, although the Budget curiously does not compare how this spending lines up against the 2% NATO commitment, and positioning Canada to meet the 3.5% NATO “hard” defence target, both affirmed in the budget text.

Based on our math, we were expecting around $43 billion in additional spending to maintain 2% and another $33 billion to move progressively toward 3.5% by 2023. The number we got is in between, so potentially Budget 2025 tangibly charts a path toward 2035 as stated recently, but with wide ranging assumptions needed for our estimates and multiple NATO spending categories, we do not know the degree of progress.

Otherwise, the Budget notes the recently announced Defence Investment Agency and the government launching a Defence Industrial Strategy in the coming months. For the latter, modest initial investments are announced and funded, but there’s no projection on its ultimate fiscal cost.

Doing more for infrastructure, making businesses more competitive

Planned infrastructure investment to the tune of $115.2 billion over the next five years is the centrepiece of the new “Build Communities Strong Fund.” It will provide $51 billion over 10 years, starting in 2026-27—about half of which seems to be new money.

This fund is expected to operate through three streams:

-

A $17.2 billion Provincial and Territorial Stream to supports provincial and territorial infrastructure projects, which must cost-match federal funding.

-

A $6 billion Direct Delivery Stream to support regionally significant projects requiring private sector investment.

-

A rebranded $27.8 billion Community Stream for local infrastructure projects.

Budget 2025 also introduces the Productivity Super-Deduction—$1.5 billion over five years. It’s a set of enhanced tax incentives that allow for quicker expense of some new capital investments. The federal government expects this will lower the marginal effective tax rate by more than two percentage points, putting it at the lowest rate in the G7.

Build Canada Homes: The budget’s centrepiece on housing

The government introduced Build Canada Homes in September. Budget 2025 confirms it will have an initial $13 billion over five years (on a cash basis). This new agency will focus on non-market housing while partnering with the private sector to leverage advanced construction techniques including factory-built, modular, and mass timber approaches.

Additionally, the government is eliminating GST for first-time home buyers on new homes up to $1 million and reducing it for homes valued between $1 million and $1.5 million at a cost of $3.9 billion over five years.

Meanwhile, CMHC is undergoing significant recalibration as part of the government’s comprehensive expenditure review with the agency winding down certain programs that do not directly increase housing supply including the cancellation of the non-operational Canada Secondary Suite Loan program. It is maintaining critical initiatives like the Apartment Construction Loan Program and supports for Indigenous housing access.

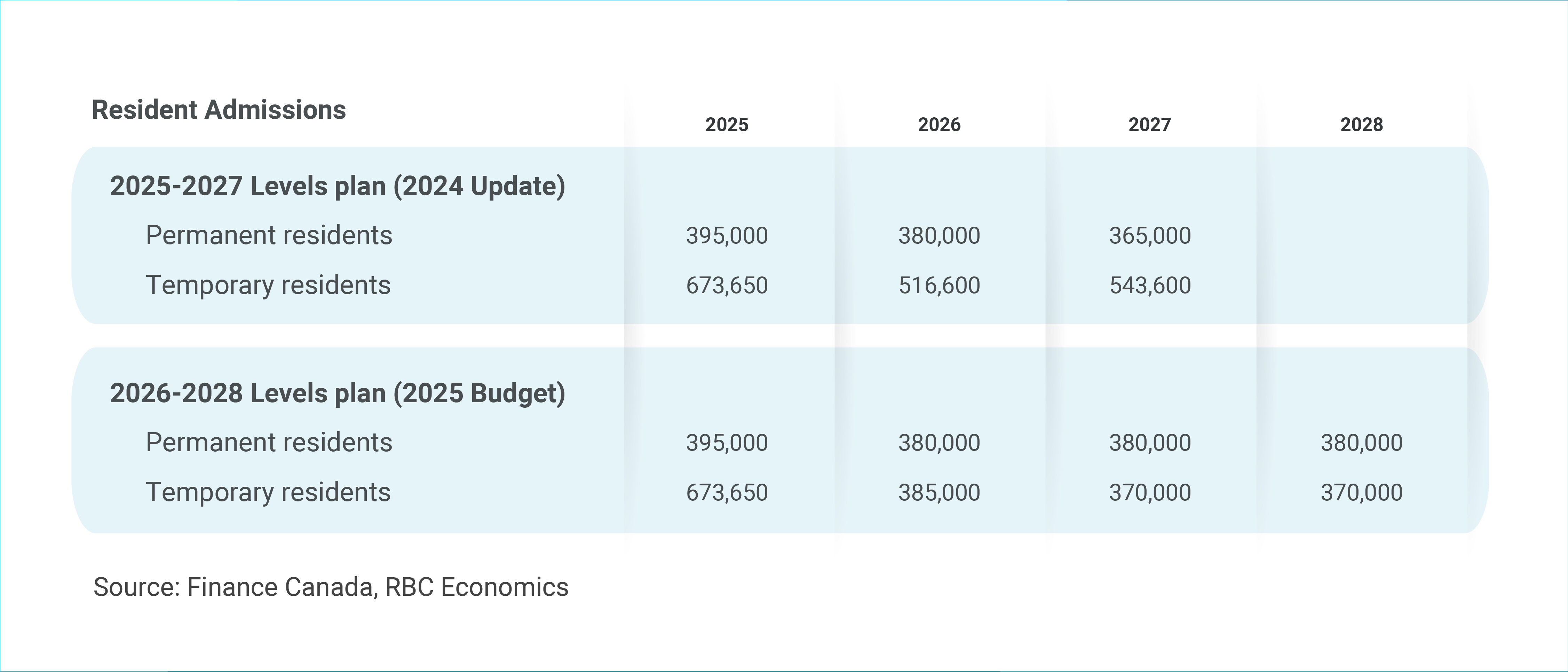

New immigration plan shores up prior targets

The new 2026-2028 Immigration Levels plan keeps target permanent resident admissions mostly unchanged—just lifting them slightly in the outer years. The big changes come on the temporary resident side where we previously wrote the government was falling increasingly short of its target to bring temporary residents down to 5% of the population by 2026, from the current 7.3%.

The new plan leverages the lever within the government’s control-temporary resident admissions-by drastically scaling them back by more than 25% versus last year’s targets. The federal government expects this will bring the share to below 5% by the end of 2027.

The new plan will also focus more on economic migrants with their share expected to increase from 59% to 64%. Part of that may reflect expectations of new H1-B entrants following the introduction of a new $1.7 billion recruitment measure aimed at attracting international talent.

We will have more to say on this following the formal tabling of the new plan.

Net financial requirement

Total financial requirements for FY25/26 of $138 billion are only $11 billon higher than the 2024 FES despite the significantly higher deficit. This even represents a $9 billion reduction relative to the July Debt Management Strategy (DMS) projection of $147 billion. The decline mostly reflects a reduced requirement in accounts payable, receivable, accruals and allowances. Non-budgetary requirements are projected higher in subsequent years, (e.g. $19 billion higher in FY26/27 versus the 2024 FES), largely due to non-financial assets. For Government of Canada bond issuance in FY25/26, there were no changes to the standalone July DMS that showed aggregate bond issuance of $316 billion. This is a record high on a net basis (excluding BoC purchases), but the steady plan was a welcome development, and the treasury bill stock is projected to decline by about $10 billion from current levels by 31 March 2026. For FY26/27, the main development was a $18 billion decline in planned aggregate bond issuance to $298 billion. Reductions are slated to come from two-year, five-year and 10-year sectors, while 30-year issuance was held steady. Green bond issuance remains at $4 billion for each fiscal year ($2.5 billion already completed for FY25/26).

– Simon Deeley, Canada Rates Strategy

About the Authors

Cynthia Leach is the Assistant Chief Economist at RBC covering the team’s structural economic and policy analysis. She joined in 2020.

Robert Hogue is the Assistant Chief Economist responsible for providing analysis and forecasts on the Canadian housing market and provincial economies.

Salim Zanzana is an economist at RBC. He focuses on emerging macroeconomic issues, ranging from trends in the labour market to shifts in the longer-term structural growth of Canada and other global economies.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.