Canada spent 2025 facing what many believed would be a catastrophic trade shock: Fears of the short- and long-term consequences from tariffs pushed consumer and business confidence deeply negative.

A narrative spun that a recession was nearly unavoidable for a country that had become so dependent on a trade partner who now looked to sever parts of its economic relationship.

And yet, Canada’s economy did not collapse. There were no two quarters of negative gross domestic product, the country added jobs, and household balance sheets improved over the course of the year.

In 2026, we see Canada further stabilizing after per-capita GDP likely improved for the first time in three years in 2025 for the many reasons we laid out here.

Still, there are many Canadians who will feel the concept of resilience is a poor description of the economies they experience. The country has become fragmented into trade-hit and trade-insulated regions.

Canada’s affordability crisis is hurting some much more than others. Businesses are hopeful about the country’s potential to diversify trade and boost productivity, but these are not likely to help much in 2026.

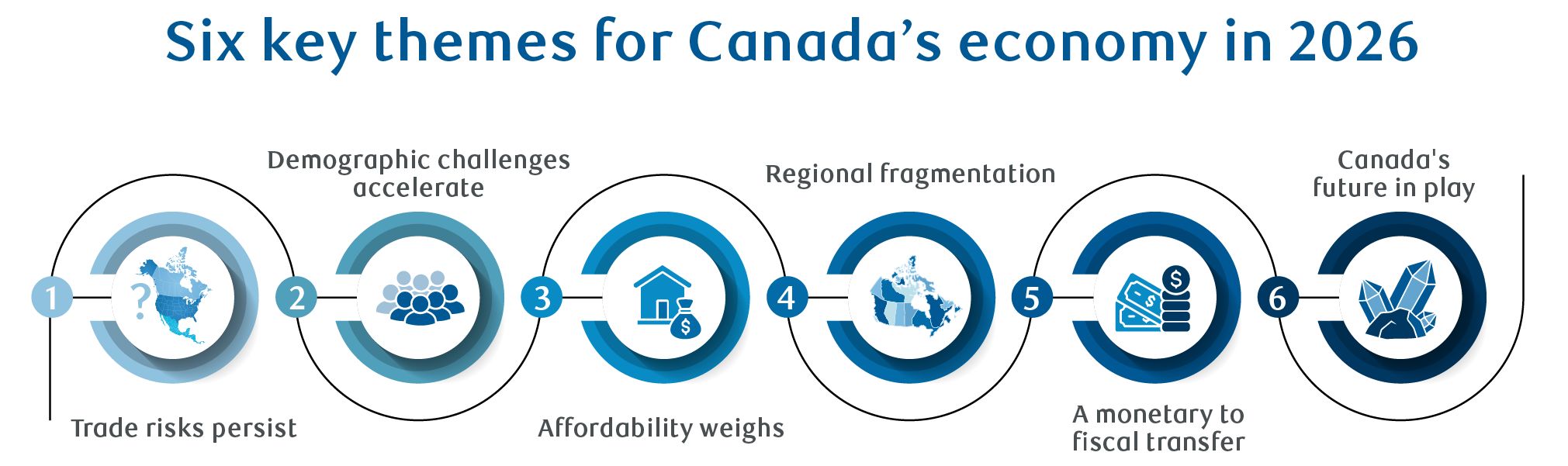

Since Canada cannot be summarized by a GDP number, in the coming year, RBC Economics will focus on six big themes that dive deeper than a traditional economic forecast. We will tackle trade risks, demographics challenges, regional fragmentation, weighing affordability, a monetary to fiscal transfer and the future at play.

Trade calibrations continue

Core to Canada’s economic resilience in 2025 were the almost 90% of exports to the United States that were exempt from tariffs, because the products were compliant with USMCA (CUSMA in Canada) trade.

The fate of that exemption will be a core focus in 2026 as discussions to extend CUSMA beyond its scheduled expiry in 2036 kick off in the summer. If an extension agreement is not reached this year, CUSMA remains in place, and the parties meet each year until 2036 to extend it.

Focus on particular meetings about CUSMA’s extension will likely dominate headlines, and influence confidence in and around Canada. But it is, perhaps, myopic. Recall that CUSMA includes a separate option (not tied to scheduled renegotiations) for any country to opt out of the agreement with six months’ notice.

Meanwhile, the agreement hasn’t prevented significant sector-specific tariffs from being imposed on products like steel, aluminum, copper, lumber, and vehicles. And, while policymakers meet on the trade deal, Canada is still in the early phases of recalibrating its economy towards new products and customers—an awakening that will progress regardless of Washington-Ottawa conversations.

As exposed as the country still feels to these conversations, it’s worth highlighting that Canada is entering the conversation with an unemployment rate that looks to have passed its peak, inflation now closer to 2%, and lower interest rates. The U.S., however, has seen job losses accelerate and price pressures mount.

This is perhaps motivating the expanding list of products exempt from broad-based reciprocal U.S. tariffs originally announced on all countries except Canada and Mexico in April.

The latest U.S. announcement to exempt a large subset of food and agricultural products from tariffs was in direct response to household affordability concerns. The full list now covers more than a third of U.S. imports from 2024 by our count. This may be a signal the appetite for a deepening protectionist agenda is fading.

Trade uncertainty will persist over the course of 2026, but our focus will be on the long legs of this transitional moment, and perhaps a bit less on the headlines around the CUSMA extension itself.

Demographic challenges compound

As federal in-migration policy reversed late 2024 and into 2025, the economy had already begun to see the impact: Q3 saw the largest, and second ever decline in Canada’s population, going back to 1946.

In 2026, this recalibration of in-migration volumes and types will be a dominant theme. We expect year-over-year population growth to be flat. That’s below the pre-pandemic average of 1.1%, and significantly lower than the nearly 3% growth experienced in 2023 and 2024, which overwhelmed the economy’s ability to absorb it.

There will be a range of implications including for rental markets, the pool of available labour, wage growth, and even post-secondary education funding. And yet, per-capita GDP should start to heal after three years of particular weakness, as growth outpaces the increase in the number of those that need to share it.

Perhaps most interestingly, Canada will need to create far fewer jobs to match the number of people looking for work. This so-called “breakeven rate” of job creation may fall to zero, or lower in 2026—such that Canada can slow job creation meaningfully, and the unemployment rate will not rise.

Immigration is not the only demographics story of 2026. In the background, there’s a shift downwards in labour supply from aging baby boomers. Over the next five years, the country will be at peak population aging as the final and largest baby boomer cohort reaches 65.

Rise of the regional economies

Canada as a whole has shown resilience in 2025, but that headline masks vastly different crosswinds impacting provinces and local economies.

In 2026, viewing Canada’s story in contrasting local colours will become even more important. Some regions are seeing positive momentum, others are hitting major headwinds, and some are experiencing a mix of both.

There are U.S. trade-impacted provinces—namely Ontario and Quebec—for which trade headlines will be the dominant macro theme. This will be even more true for Southwestern Ontario, feeling the brunt of the trade shock.

Then, there are resource-rich provinces, which are commodity-price sensitive, and largely insulated from trade conflict, that are likely to maintain positions of economic strength. Alberta and Saskatchewan will grow far more than the national average, supported by energy infrastructure and agricultural output, respectively, even as they battle Chinese tariffs on agricultural exports.

Meanwhile, big drops in population growth will be felt unevenly. British Columbia leaned heavily on temporary residents as a growth engine, and is already seeing population outflows weighing on its rental market. Alberta, for example, will feel far less of this pressure.

The development of “nation-building” infrastructure and other projects, and generational investment in defence capabilities will generate substantial business activity and opportunities in many parts of the country, but not all. And, the Canadian “elbows up” mindset, driving demand for home-grown products and services, will especially benefit tourism-dependent communities.

We dive deeper into these provincial stories in the Quarterly Canadian Outlook. But, the most critical takeaway is Canada’s story cannot be told as one, but as the amalgamation of its regional colours.

Affordability pressures aren’t going away

Canada’s cost of living challenges are not new, and neither are the groups most impacted by them.

The post-pandemic surge in inflation coupled with a historic rise in interest rates created a fresh affordability shock for Canadians that continues to weigh today. Since January 2020, prices measured by the Consumer Price Index have risen about 20%—below wage increases of 25% over the same period—suggesting some real income growth.

However, prices for essentials including food and housing have grown much faster, both at about 30%, well outpacing wage growth. For lower-income Canadians, who spend more of their income on food and rent, this type of inflation hurts more.

Meanwhile, Canadians holding larger debts have disproportionately felt the burden of higher interest rates, while those with savings have seen the benefits. And, a booming stock market has improved household balance sheets for those with financial assets, and not for those that don’t.

As we enter 2026, inflation is set to moderate to just above 2% (that still means prices will rise, but at a slower pace). The Bank of Canada has lowered interest rates, the unemployment rate will likely improve, and house price growth—especially in Ontario and B.C.—will moderate.

And yet, structural affordability challenges remain at the forefront. In particular, how persistently elevated house prices, weaker job market prospects for some groups (including those more affected by emerging technology), and the prospect of ongoing equity market strength interacts with the prospect of higher wages given lower labour supply going forward as the final, and largest, baby boomer cohort leaves the labour market.

Affordability isn’t a one size fits all narrative. In 2026, our research will dive more deeply into its short- and long-term drivers, and solutions.

The monetary to fiscal handoff

The BoC cut rates four times in 2025, bringing a total of 275 basis points of cuts since 2024. Easing of monetary policy has helped reduce the mortgage refinancing shock for homeowners, and debt burdens of many Canadians.

At the same time, the central bank has frequently emphasized that monetary policy is not always the best tool to support the country. Governor Tiff Macklem laid the foundation of this view on Feb. 6 in a speech just days after the U.S. launched its trade war with Canada. “Monetary policy can’t do everything. We need to avoid the temptation to overload monetary policy by expecting more of it than it can deliver,” he said.

Indeed, the trade shock has laid bare the limits of central bank powers. For one, the BoC has one tool it applies to the entire country, but the trade shock created pockets of tremendous economic weakness while sparing others.

Moreover, interest rate policy can do little to support the structural changes needed to navigate economic forces like increasingly severe and frequent weather events, geopolitical crises, trade wars, or population policies. Like taking a pain killer to address a broken arm, monetary policy helps around the edges of these problems but, alone, it cannot heal what ails or build the country’s future.

This is not a uniquely Canadian challenge as these structural forces limiting the influence of monetary policy impact countries around the world. And, just like most Western economies, Canada is increasingly turning towards fiscal policy—both federally and provincially—to provide support for near term economic weakness, and also build for future resilience.

Indeed, on paper, federal and provincial fiscal impulse could be very high the next couple years, propelled by the recent federal budget. A high share of new funding is slated for defence and infrastructure, which typically produce more material impact on spending and growth within the three-year period. And, there’s still plenty of excess capacity in the economy in the near term to absorb fiscal stimulus. Our forecast adds 0.4 percentage point to GDP growth in 2025 and 2026. That’s decent stabilization coming from this type of policy.

Monetary and fiscal policies’ relationship has always been a delicate dance, but Canada is likely to see leadership shift from the central bank to the government.

Canada’s growth pivot starts to take shape

Addressing Canada’s structural economic weaknesses will not be quick or easy, but the seeds of its transition will become more apparent in 2026.

Private investment is key. But, even with firmer growth into 2026 in our outlook, the gap left by low business investment in recent years is large. Let alone the sustained private investment gap versus the U.S. since at least 2014.

Fiscal strategies include using government investment incentives, and spending to boost growth and confidence so business investment can accelerate. Corporate Canada’s after-tax profits have remained elevated post-pandemic but to date it’s been paid out as dividends and other distributions.

There is some evidence the private sector is adapting to U.S. and Chinese tariffs through export diversions to other countries. Canada’s exports to non-U.S. economies have been up year-over-year since March 2025, even though total and U.S. exports are down.

However, Canada’s trade relationship with the U.S. is more than a reliance—it’s an orientation, requiring new supply chains, and major new infrastructure to rebalance goods trade with other regions.

The other pillar is relying on major projects and defence investment to spur near-term growth, and long-term productivity. As per above, we don’t expect these activities will materially drive the Canadian economy in 2026, but we do expect to get a better read on how they are progressing, and their potential to be transformational.

About the Authors

Frances Donald is the Chief Economist at RBC and oversees a team of leading professionals, who deliver economic analyses and insights to inform RBC clients around the globe. Frances is a key expert on economic issues and is highly sought after by clients, government leaders, policy makers, and media in the U.S. and Canada.

Robert Hogue is an Assistant Chief Economist, responsible for providing analysis and forecasts on the Canadian housing market and provincial economies.

Nathan Janzen is an Assistant Chief Economist, leading the macroeconomic analysis group. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States.

Cynthia Leach is the Assistant Chief Economist at RBC covering the team’s structural economic and policy analysis. She joined in 2020.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.