With unemployment rising in the last three years, it can be easy to forget that the largest (and final) baby boomer cohort is about to reach official retirement age.

It will take time for current labour market weakness to unwind — although we believe we’re nearing peak unemployment, our base case outlook has hiring demand growing slowly as trade-exposed sectors continue to face weakness, and consumer spending only firms towards the end of 2026.

Beyond that, a structural reduction in labour supply will be felt more acutely across the economy. It means that despite current labour market weakness, Canada must prepare for tomorrow’s tighter market.

Labour supply to fall significantly

Almost fifteen years since the first boomers turned 65, we’re more than two-thirds through boomer retirements. The departure of an estimated 5.2 million boomers from the labour force has led to a structurally tighter labour market. The average participation rate fell by 1.6 percentage points between 2010 and 2024 despite a 2.3-percentage-point increase among prime age (25-54) workers.

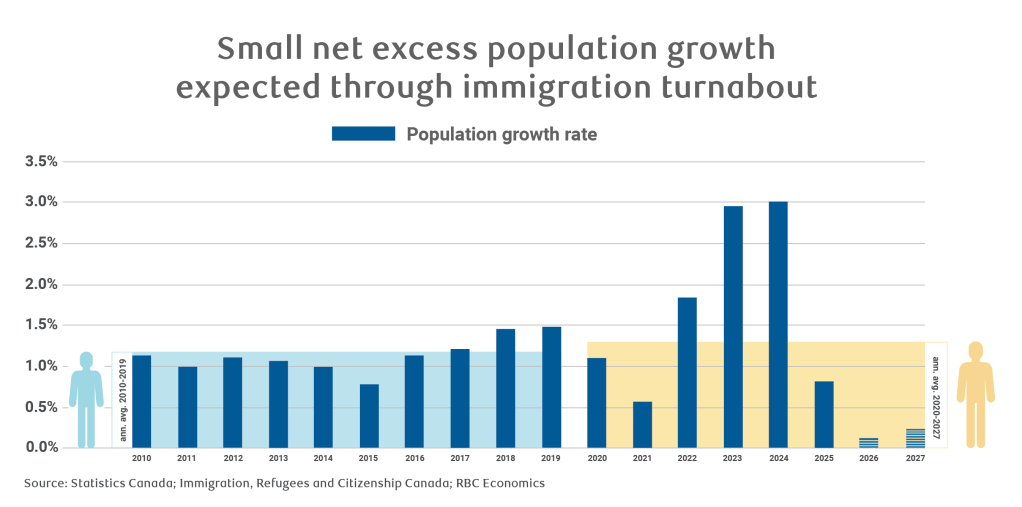

Remaining boomers will reach age 65 by 2030, bringing the largest retirement wave yet. A key question is whether high levels of in-migration in recent years (permanent and temporary residents) will have helped to stall aging of the labour force. After all, net migration represents effectively all of Canada’s population growth, and high levels of prime age in-migration led to a dip in the country’s median age between 2022 and 2024— defying the trend since at least 1971.

The answer is no, given the federal government’s current in-migration policy reversal. Near-zero population growth is expected in 2026 and 2027 under new and drastically lower targets. Annual average growth between 2020 and 2027 would be barely above the 2010-2019 average. In other words, Canada’s immigration lurch will have contributed an extra half year of cumulative population growth at most.

Assuming in-migration returns to a more normal rate of 0.9% of the population post-2027, we expect more than a 2 percentage point decline in labour force participation between 2024 and 2030. This would exceed the drop of the prior fourteen years—meaning Canada will face the peak impact of boomers on the labour force.

Continued declines in the participation rate are in the cards even if population growth overshoots the federal target. A longstanding finding for Western economies is that only sustained high levels of in-migration would flatten participation rates. Higher population growth would directionally mitigate aging impacts, but Canada would need to see annual in-migration much higher – i.e. north of 2% of the population – to get closer to flattening the participation rate by 2030.

Meanwhile, the untapped domestic labour pool could remain low after cyclical unemployment is wound down. The prime age participation rate is historically high at 89%, and more than 95% of those not in the labour force say they do not want a job. It means Canada needs to accept that, viewed from the supply side, it’s headed toward an even structurally tighter labour market within a few years.

Aging pressures are felt unevenly

Labour supply pressures could be felt sooner in sectors where there are older workers. Nine of 21 NAICS industries have more than a quarter of employees over age 55, above the 21% economy average. Fishing and agriculture have shares around 40%.

Some sectors have already experienced close to a doubling, or more, in annual retirement churn as a share of the labour force compared to the average 50% increase. This includes business, building and other support services, wholesale trade, non-durable goods manufacturing, and agriculture. British Columbia, Quebec and the Atlantic provinces have higher median ages and share of older people.

Meanwhile, the aging population will likely continue to shift demand towards services. Health care and social services have persistently had above average job vacancy rates since the pandemic.

Post-boomer reprieve coming for labour force but so is age-related spending

Five years out from boomers all becoming 65-plus, Canada can look forward to a reprieve from compounding aging effects. Gen X is notably smaller than the boomers. It won’t be felt until the mid-2030’s, but the labour force participation rate could nearly stabilize for a period, provided demographic parameters remain close to today’s values (see chart footnote).

Over the longer term, though, the country will continue to age and the participation rate will fall. Ultimately, Canada will need to continue to pay the piper of low and falling fertility1, given immigration is only a partial offset, but the cheque will be smaller than with the boomers.

Even then, the 2030’s are too early to be past the full imprint of boomers on the economy. We estimate the country has seen only 11% of the additional health care costs of the aging boomers. The Canada/Quebec Pension Plans have been funded programs since the late 1990s, but federal Old Age Security entitlements and provincial health care costs remain unfunded liabilities.

Annual health care costs escalate quickly in old age from about $3,400 in 2022 at age 40 to $10,000 at 70, and more than $36,000 at 90. Canada’s rising seniors’ dependency ratio—the mirror of the falling participation rate—means there are relatively fewer workers to shoulder this burden.

Measures to address aging pressures will have benefits beyond boomers

Recently reminded of the limits of immigration, Canada has been forced to pivot and find alternate ways to grow its labour force and economy.

We have written about incremental ways to expand the domestic labour pool before through employee training, skills recognition, enhanced labour mobility and recruiting more women and other demographic groups where participation rates are lower than average. A lot of the burden, though, will fall to the other determinants of potential economic growth such as capital intensity and productivity-enhancing innovations. Addressing rising health care costs would manage fiscal pressures.

None of this will be easy with geopolitical uncertainty hanging over business investment, and many structural changes needed to make a difference. Yet, the currently weak labour market, and approaching end of boomers reaching age 65 should not lull the country into complacency. Structurally tighter labour markets are coming and measures to address it will have benefits that outlive the last of the boomer wave.

Cynthia Leach is Assistant Chief Economist at RBC covering the team’s structural economic and policy analysis. She joined in 2020.

- Falling fertility means families having fewer children resulting in the number of children per woman falling below levels needed to replace an aging population. ↩︎

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.