The past few years have been incredibly hard for many Canadians. The pandemic caused massive disruptions to the job market and the highest rates of inflation in decades, which was intensified by the war in Ukraine. And now comes a trade war with the U.S., with its own set of shockwaves, including job losses and supply-chain upheaval, sending the price of goods even higher. Many can’t keep up.

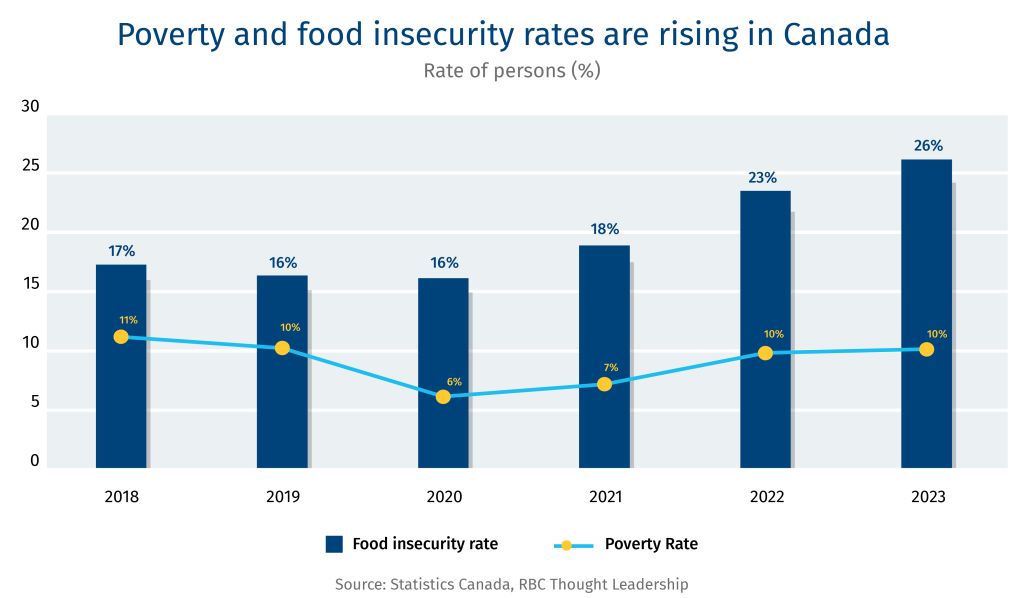

Today, one in four Canadians are experiencing food insecurity. That’s 10 million people—a level never seen before in this country.1 Ultimately, it’s an issue of affordability. There is an abundance of food available. But for an increasing number, it’s out of reach. In March 2024, more than two million visits were recorded at Canadian food banks. That’s a 90% increase in just five years.2 And food banks are a last resort, signalling how dire things have become. Properly supporting and resourcing food banks is critical. However, addressing food insecurity longer term, relies on building a stronger Canadian economy. This includes addressing the affordability crisis, improving productivity, and advancing durable economic development in Canada’s rural and remote areas.

Trade war on food: Rising job loss, costs, and disruptions

Job loss and insecurity is forcing many to make difficult choices

U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade war has caused widespread uncertainty. Launches have been delayed. Production has been paused. Layoffs have been announced. Between January and May, Canada’s manufacturing sector lost 54,000 jobs and the country’s unemployment rate rose to 7%, the highest it’s been since 2016, excluding the pandemic.3 4 Trade exposed industries, including manufacturing, continue to scale down jobs, and now there is greater uncertainty in steel and aluminum jobs with Trump’s 50% tariff on the industry. All this volatility can leave workers in precarious financial situations.

The average Canadian household spent about $76,750 on goods and services in 2023, with 15% and 32% of their money spent on food and shelter, respectively. The lowest income quintile spent $40,080 annually—nearly half that of the average household—with 18% spent on food and 35% on shelter.5 In the event of a job loss—or the fear of potential layoff—Canadians in higher income brackets can cut spending on discretionary items (e.g., new clothes, meals out) in the short term. Lower-income households don’t have that luxury and are left with difficult choices between what basic needs—utility bills, medication, food—they’ll cover. These choices can also impact the quality of food purchased, with lower income households opting for cheaper, lower-nutrient-rich foods.6

Like downturns in the job market, swings in international commodity markets impacted by tariff wars can impact Canadians whose income is directly tied to market prices. Farmers are often price receivers—unable to pass rising costs onto buyers and consumers. And China’s tariffs on agri-food products including canola oil and seafood have recently taken a toll on Canada’s rural economy. Nova Scotia is thought to be the hardest hit by China’s 25% duties on aquatic products, which represented 9.2% of the provinces total export value in 2024. Farmers and fisherpersons are familiar with volatility in the marketplace from bad weather to shifts in demand. Still, ongoing disruptions can erode stability in rural and remote regions that are already at a disadvantage in accessing economic opportunities and services.

And the impact of tariffs is not just about job security. Windsor, Ontario, for example, is reliant on automotive and advanced manufacturing, food processing, and grains and oilseed handling and shipping. This exposes the entire city and surrounding area to Trump’s tariffs on auto as well as China’s retaliatory tariffs on Canada’s agri-food products. Unemployment in Windsor is higher than the national average at 10.8% in May 2025, up from 7.8% in May 2024.7 And the knock-on effects from multiple pressures on employment within a region and rising costs of living can trickle down to local retail and services. As consumer spending tightens, all sectors and their workers are impacted.

Rising cost of living threatens to further deepen the food insecurity crisis.

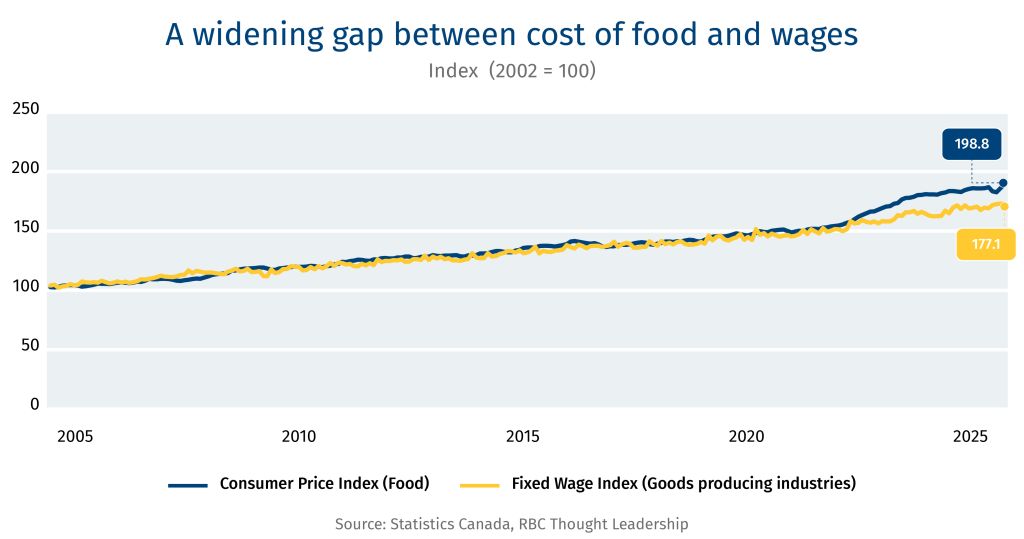

With rising costs in Canada, a job is no longer a precursor for meeting basic needs. More than 60% of Canada’s food-insecure households rely on wages, salaries, or self-employment income as their primary source of income.8 Workers experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity often occupy low-wage or precarious jobs that are not keeping pace with the cost of living. Visible minorities, women and new immigrants in Canada earn less than the national average. As a result, food insecurity is disproportionality experienced by these groups. More than 46% of black households and 39% of the Indigenous population living off-reserve are food insecure.9 Single-mother households also have higher rates of food insecurity at 52%.10

The effects of food insecurity further marginalize vulnerable groups. Food insecurity is associated with higher rates of chronic diseases, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease. This means more visits to the doctor’s office and the hospital. Severely food insecure Canadians incur health costs that are more than double those who are food secure.11 Food insecurity also impacts the physical and mental development of children, as well as academic performance and behaviour.12 These impacts underline the health and socio-economic costs to families and the Canadian economy.

Over the past five years, the affordability crisis has been acutely experienced by households whose wages are not keeping pace with the rising price of goods and services. With pre-tariff inventory coming off grocery store shelves, tariffs are starting to intensify the unaffordability of products in Canada, especially food. Since January 2025, food prices have been a notable driving factor growing the Canadian Consumer Price Index. In April 2025, food prices increased by 3.8% from last year.

Supply chain disruptions impact food consistency and costs

Food companies and retailers reported loses in the first quarter—a direct result of the tariff wars.13 On top of mitigating losses, Canada-U.S. agri-food supply chains are now tasked with additional administrative demands in proving the Canada-United States-Mexico (CUSMA) trade agreement compliance as only two-thirds of Canada’s agri-food exports in 2024 were traded under CUSMA. These stacking complexities and added costs cannot only be absorbed by agri-food suppliers, wholesalers, and retailers, who often operate on thin margins. Eventually rising costs are passed onto the consumer. In the U.S., the impact of tariffs is estimated to increase food prices by 2.6% in the short run, disproportionately impacting fruit and vegetables, that are expected to rise 5.4%.14

Trade wars have sparked a diversification movement. And while trade diversification is a strategy to grow and strengthen Canada’s agri-food exports, it can also result in trade-offs such as short-term uncertainty in quality and cost for consumers while supply chains are being established. Stability and consistency in trade is a key factor in keeping transportation, logistics and operational costs down for traders, wholesalers and retailer, which helps ensure consumers have consistency in price, quality, and availability. Now, uncertainty from tariffs jeopardizes these benefits that North American consumers have become accustomed to through Canada and the U.S.’s interconnected supply chains.

The next step: Tying food solutions to Canada’s growth ambitions

Solutions to food insecurity in Canada are well documented but the issue remains on the sidelines when it comes to large-scale policy and funding commitments.

Potential solutions include:

-

Address the disparity between Canada’s rural and urban as it relates to access to resources, living wages, and economic development opportunities.

-

Rebuild Canada’s social safety net to better support low-income households and proactively respond when a household has lost income or has experienced a disruption that impacts its budget.

-

Improve the affordability of housing.

A food security target may be the catalyst needed to pull these solutions together to drive action across Canada and track progress. This is not a new idea. Food security experts in Canada have called for a 50% target by 2030.15 16 But now is the time to implement a bold vision for food security in Canada as the country sets out to build back a better economy. A key challenge is identifying where food security solutions can be aligned with existing landmark commitments to build momentum. A food secure plan for Canada must also consider how it proportionally improves rates in regions and among groups that are the worst impacted.

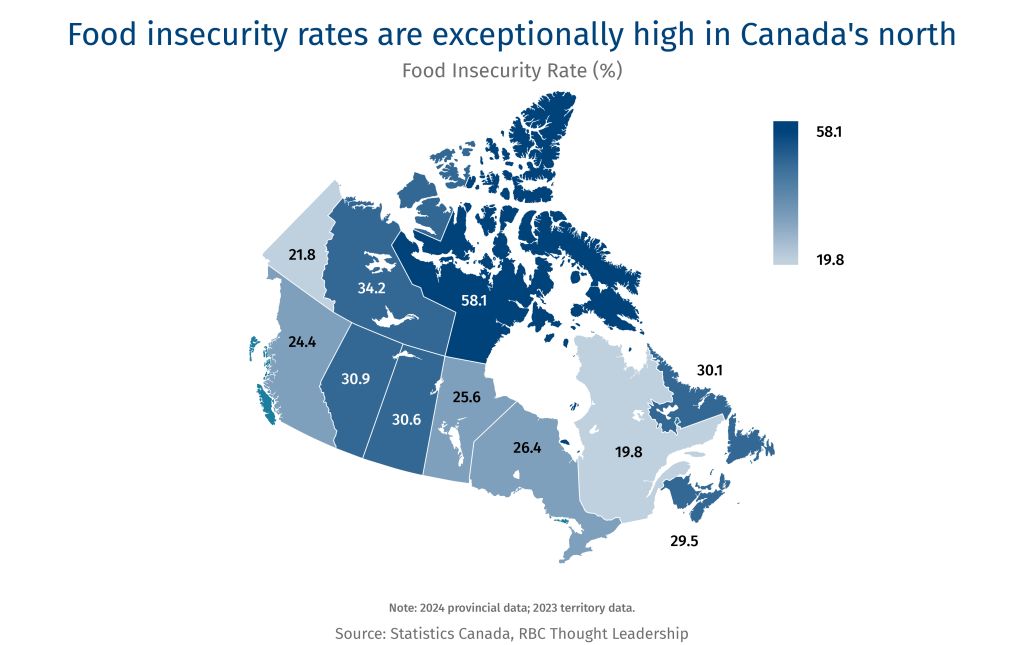

Expedite the development of rural and remote community and health services alongside efforts to expedite Canada’s major infrastructure projects. Canada’s ambitions to accelerate major infrastructure projects from the Port of Churchill to the Ring of Fire are primarily concentrated in northern rural and remote Canada. Canada’s rural and remote areas account for 25% of Canada’s GDP but are grossly underserviced when it comes to health care, housing, and other basic needs, including access to healthy food.17 Food insecurity is high across Canada but is highest in northern and remote areas. More than 58% of people in Nunavut experience food insecurity. Further, only 7% of doctors work in rural areas despite the fact Canada’s rural population accounts for 18% of the total population.18

Much of Canada’s plans to build its economic security and sovereignty hinges on having a productive workforce in rural and remote Canada. But getting people to stay in rural and remote areas or relocate for these projects is a tough sell if they can’t access resources needed for their families to lead a healthy life. Canada can help flip the trend of urban areas growing 15 times faster than rural by mitigating brain and resource drain through investments in community resources including access to healthcare, food and housing that match the ambitions of major infrastructure projects.19

Improving access to household financial supports and benefits through policy reform. It is especially timely to advance such reform efforts as the Liberal government has committed to review and reform the process of applying for the Disability Tax Credit (DTC). The DTC is the gateway to key federal programs, including the Canada Disability Benefit, the Canada Child Benefit for children with disabilities, and the dental benefit. This review process is an opportunity to engage Canada’s network of food banks servicing families that rely on DTC benefit to develop practical solutions that work for households, especially those experiencing housing and food insecurity.

On top of qualifying for benefits, Canada’s most vulnerable groups, including those with disabilities and houseless people, are often the hardest to reach populations for tax returns, and have filing rates below Canada’s national average of 92%.20 Unfiled taxes and unclaimed returns account for more than 8.9 million uncashed Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) cheques, totaling $1.4 billion.21 The value of household tax credits won’t solve a household’s financial challenges, but it’s a start.

Building upon CRA’s automatic tax filing pilot and approaches to streamline and simplify tax filing, there is an opportunity to explore support services that better position Canadians to navigate administrative processes to qualify and access credits. And to learn from community organizations including food banks who offer “wrap around services” such as food and financial literacy programming for Canada’s most vulnerable and marginalized populations.

Align food security objectives with Canada’s home building boom. Cutting housing costs can transform a household’s budget. The new federal Liberal government’s plan to build 500,000 homes a year would boost the economy and address a critical need: one of the priority functions of Canada’s forthcoming entity “Build Canada Homes” (BCH) is to build affordable housing at scale. This priority includes a $6 billion commitment for deeply affordable housing including supportive housing, Indigenous housing, and shelters. Complementary to building these homes rapidly and setting homelessness targets with provinces, government could also consider aligning with national food security targets and activities as a measure of their success in affordable housing and enabling people to achieve a healthy, more productive lifestyle that in turn contributes to growing Canada’s economy.

Food insecurity is a systemic problem, requiring systems-based solutions. As Canada embarks on its pro-growth era, it is opportune to consider how its unified approach can be applied to address the most chronic symptoms of a poor economy—food insecurity and poverty.

Experiences and approaches from around the world

Food insecurity affects every country, and over 295 million people worldwide face acute hunger.1 Countries are taking different approaches to measure, monitor, and mitigate the issue, which extends far beyond food programming and policy into income, housing and social equity domains. However, advanced economies like Canada are increasingly expanding food programming to counter the short-term impacts food insecurity is having on communities.

More than 7 million people, or 11% of the population, in the U.K. are living in food insecure households.22 And one-third of children in the U.K. are living in poverty. To tackle this challenge, the government launched a Child Poverty Taskforce.23 The U.K. also has a few notable programs that directly relate to food access such as:

-

Free school meals program provides meals for children and young people during school with standards on the nutrition of food offered. Complementary to school meals, the UK launched Holiday Activities and Food (HAF) in 2022 to improve access to food and resources during school breaks.24

-

Healthy Start vouchers in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland support people on low incomes to access pre-natal vitamins, infant milk formula, and healthy food for young children. In Scotland an equivalent Best Start Foods program launched in August 2019.

-

Household Support Fund: Allocated £1.5 billion in 2022/23 to help with household essentials, including food, energy and housing bills.

The U.K. is also undergoing its largest home building campaign since World War II. The lack of affordable housing and its impact on household stability and spending is a key driver for this building boom. The campaign goes as far as outlining a plan for creating a dozen new towns of approximately 10,000 homes each.25

In New Zealand, 27% of households with children ran out of food often or sometimes in 2023, up from 14.4% in 2021.26 In response to rising rates of food insecurity, New Zealand led the development of a 10-year food security roadmap for the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) covering four key areas: digitalization, productivity, inclusivity and sustainability. APEC includes 21 member countries across the Pacific Rim, including Canada.

Food security research, policy and programming are delivered under multiple ministries in New Zealand, including health, education, and social development ministries, signalling the recognition of food insecurity’s impact on human health and wellbeing. Within New Zealand there has been a growing movement to improve access across its four main regions to resources for basic needs and to improve healthy living standards:

-

Launch of the Public Health Advisory Committee in 2022, which was asked in 2023 to review New Zealand’s food system and provide advice and recommendations, which are presented in the 2024 report, Rebalancing Our Food System.

-

New Zealand provides some government funding to maintain community food distribution infrastructure and support regional community food hubs under its Food Secure Communities program, which was established in 2020.

-

Ka Ora, Ka Ako (Healthy School Lunches Program) was launched in 2019 to provide free lunches to students attending schools in low-income areas. The program is active in over 1,000 schools and provides meals for nearly 240,000 students every day.

Food insecurity affected 47 million Americans in 2023. The U.S. has experienced a similar post-pandemic trend to Canada with the rate of food insecure households rising from 10% to 14% between 2021 and 2023.27 Among those in the OECD, only Costa Rica has higher levels of income inequality. And proposed legislation such as, One Big Beautiful Bill Act, risk worsening inequality in the U.S. by raising national debt and potentially triggering cuts to programs that are designed to reduce food insecurity and improve food access, including:

-

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) provides a restricted subsidy to purchase food. SNAP serves an average of 42.2 million people per month (12.6% of the US population).28 Participating in SNAP for six months has been shown to decrease food insecurity by 5-10 percentage points and is even more effective for children and those with very low food security.29 30 SNAP has also shown to positively impact local communities’ economic activity and job creation.

-

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) provides a restricted food subsidy for pregnant and post-partum people, infants and children up to five years old who meet both income- and nutrition-based eligibility criteria.31 In 2023, the federal government spent US$6.6 billion on WIC program, reaching an average of 6.6 million people per month.32

Our Project Partners

Download the Report

Contributors:

RBC Thought Leadership

Lisa Ashton, Agriculture Policy Lead

Maple Leaf Centre for Food Security

Sarah Stern, Executive Director

Arrell Food Institute at the University of Guelph

Evan Fraser, Director and Professor

Pauline Cripps, Community Food Lead

-

Statistics Canada. Food insecurity by economic family type, 2025.

-

Food Banks Canada. HungerCount 2024, 2024.

-

Statistics Canada. Labour force characteristics by census metropolitan area, three-month moving average, seasonally adjusted, 2025.

-

Statistics Canada. Employment by industry, monthly, seasonally adjusted and unadjusted, and trend-cycle, last 5 months (x 1,000), 2025.

-

Statistics Canada. Household spending by household income quintile, Canada, regions and provinces, 2025.

-

French et al. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: the SHoPPER study, 2019.

-

Statistics Canada. Labour force characteristics by census metropolitan area, three-month moving average, seasonally adjusted, 2025.

-

Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA, Tarasuk V. Household food insecurity in Canada (2022), 2023.

-

Statistics Canada. Food insecurity by selected demographic characteristics, 2025.

-

Statistics Canada. Food insecurity by economic family type, 2025.

-

Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2005, 2007-2008, 2009-2010, Ontario administrative health databases. Adapted from: Tarasuk, Cheng, de Oliveira, Dachner, Gundersen & Kurdyak (2015)

-

Gallegos et al. Food Insecurity and Child Development: A State-of-the-Art Review, 2021.

-

Pepsico. PepsiCo Reports First-Quarter 2025 Results; Updates 2025 Financial Guidance, 2025.

-

The Budget Lab at Yale. State of U.S. Tariffs: April 15, 2025

-

Food Banks Canada. Joint Open Letter: Cut Food Insecurity in Canada in half by 2030, 2025.

-

Beardsley, McCain, and Saul. Let’s commit to cutting food insecurity in half, 2022.

-

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. Rural Economic Development.

-

Canadian Institute for Health Information. A profile of physicians in Canada, 2025

-

Statistics Canada. Census in Brief, 2022.

-

Canada Revenue Agency. Statistical report on the participation of the hard-to-reach populations in the tax and benefit systems, 2024.

-

Canada Revenue Agency. Approximately $1.4 billion in uncashed cheques is sitting in the Canada Revenue Agency’s coffers, 2022.

-

UK Parliament. Who is experiencing food insecurity in the UK? 2024.

-

Government of the United Kingdom. Tackling Child Poverty: Developing Our Strategy, 2024.

-

Government of the United Kingdom. Guidance: Holiday activities and food programme 2024, 2025.

-

Government of the United Kingdom. Government unveils plans for next generation of new towns, 2025.

-

Ministry of Health. New Zealand Health Survey, 2025.

-

USDA Economic Research Service. Food Security in the U.S. – Key Statistics & Graphics, 2025.

-

USDA Economic Research Service. SNAP in Action, 2025.

-

USDA Economic Research Service. Measuring the Effect of SNAP Participation on Food Security, 2025.

-

Johnson-Green and Claflin. Gender and Racial Justice in SNAP, 2021.

-

USDA Economic Research Service. WIC Program | Economic Research Service, 2025.

-

USDA Economic Research Service.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.