Key Takeaways

Tackling Canada’s housing shortage will require $2 trillion in capital deployment over the next 5 years—that’s a 5X increase from current levels

Two taxation tools—tax-free municipal bonds for housing and infrastructure, and tax credits for affordable housing—have spurred housing supply in the U.S., attracting $5 in private capital for every $1 of foregone taxation revenue

Municipalities could cut housing costs by 20% by financing infrastructure with municipal bonds.

The housing shortage in Canada has reached a crisis point.1 An estimated 3.5 million new homes are needed to keep up with demand.2 A staggering number, especially compared to the U.S., where the shortage is 12 times smaller, on a per capita basis, despite having eight times the population.3 Canada’s growing housing shortage has contributed directly to affordability challenges. Average home prices have sky-rocketed in recent years—particularly in Ontario and British Columbia, which accounts for two-thirds of the country’s shortage—such that prices are now nine times household income.4

The federal government proposed a National Housing Strategy in 2017. But the program has only delivered 10% of its commitment to build 131,000 affordable rental homes.5 Mark Carney’s government has now pledged to spend the bulk of its $36-billion housing commitment on prefabricated homes. Tax cuts and concessionary financing for developers round out the government’s policy package.

It’s a start, but more can be done. The U.S. approach to housing can be instructive in how to attract continuous private capital into homebuilding. Canada and the U.S. both provide government subsidies to encourage developers to build more affordable rental and ownership housing. Canada’s preference is grants or concessionary financing, for rental housing, and waiving of government fees, and downpayment support for first-time homebuyers.6 This policy playbook requires the federal government, and provincial governments to a more limited extent, to fund these programs through direct capital outlay.

The U.S. relies more on federal tax incentives to draw in money from corporate, institutional, and mom-and-pop investors to finance housing and housing related infrastructure, including roads and stormwater sewers. At the heart of the U.S. taxation playbook are two tax tools: tax-free municipal bonds and a low-income housing tax credit for affordable housing.7 In 2024, these tools cost the U.S. Department of the Treasury a combined US$59.1 billion—1.2% of all federal revenue—but crowded in nearly US$500 billion in direct-equity investments.8

The introduction of similar federal income tax changes in Canada could achieve a housing trifecta: increased supply, improved affordability, and more sustainable homes. By our estimates, housing costs could decrease by 20%. These savings would allow developers to free up more capital, enabling them to build twice the number of projects with the same amount of equity financing. An acceleration of building activity that could help the Carney government fulfill a key priority: making housing in Canada more affordable.9

Tax-free Municipal Bonds

U.S. local governments have the power to raise debt in public markets, through bond issuances, to finance operating and capital needs, including housing. Local governments have US$4 trillion in outstanding municipal debt, and the U.S. municipal bond market is the largest, globally.10

The demand for local government debt can largely be attributed to the tax shield it provides investors. Holders of municipal debt, mainly institutional and retail investors, do not have to pay income tax on interest earned on these bonds.11 Since investors are willing to accept a lower rate of return in exchange for lowering their tax obligations, local governments can borrow from the public debt markets at lower costs, typically 100 to 160 basis points lower than taxable bonds with similar risk characteristics.12

To prevent the misuse of proceeds, the federal government places restrictions on what can be financed. Proceeds are principally used to finance projects where the benefits flow to public rather than private interests. To be considered for public purposes, bonds must meet one of the following criteria: more than 90% of the proceeds are used by a government entity, or less than 10% of the proceeds are secured for a property that is used in a trade or business. Municipal bonds that satisfy either of these conditions are classified as government bonds and the federal government does not impose a cap on the amount of debt that can be issued.

Activities that fail to satisfy either of these tests but provide both public and private benefits, such as multi-family residential housing projects, green buildings, and sustainable design projects,13 are eligible for financing with a type of municipal bond classified as a private activity bond (PAB). Unlike government bonds, PABs are subject to capital raising limits, which is US$48 billion in 2025.14 While PABs are used to fund a variety of initiatives, they are critical for developers building affordable housing projects. About 44% (or US$18 billion) of PABs are used to finance affordable rental housing projects, in 2022.15

Low-Income Housing Tax Credit for Affordable Rental Housing

A second tool in the U.S. tax code playbook are low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC). Since its inception in 1987, the LIHTC has been responsible for the development of 7.8% of new U.S. housing stock, or 3.65 million units of affordable housing.16

Two types of credit exist, a 4% and a 9% tax credit.17 The 9% tax credits are allocated to states annually by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). In 2025, credits are capped at $49.6 billion. States distribute these credits to eligible projects, and eligibility criteria is refreshed annually, to remain aligned with each state’s affordable housing priorities, including the construction of greener or more energy efficient homes. The 4% tax credits are awarded automatically to projects that receive 50% of funding through tax-exempt municipal bond financing. There’s no ceiling on the amount of 4% tax credits available each year, since developers apply for the credit directly with the IRS.

While there are several approaches to accessing the 9% tax credit, the most common is for a syndicator, typically a bank, to play match maker between developers and investors. A limited liability corporation (LLC) is formed in which investors are the limited partners owning 99.99% of a housing project, and the developer as the general partner owns 0.01%. The developer flows to investors the tax credits they receive from their state housing finance authority once a project is occupied. Investors in return provide equity financing to developers, that’s generally $0.90 on the dollar for a credit. These investment partnerships are structured to last 15 years, which is the mandated affordability period in the tax code. At the end of the 15-year holding period, the investors, who are mainly corporations, have the option to sell the housing project back to the developer or enter a new deal for the same property.18

Investors in LIHTC are mainly motivated by the after-tax returns on their equity investments. As a result, they are comfortable with providing 80% equity financing for a project where they will receive lower returns because their contributions will be used to lower rents. Investors internal rate of return (IRR) of after-tax savings range from 350 to 800 basis points which on the upper end of the IRR range is almost twice the yield of a 12-month U.S. treasury bond.19 Two forms of tax savings exist—general tax savings and income tax savings. The former is realized through asset depreciation and operating losses. Income tax savings are realized by using the tax credits to offset federal income tax liability for 10 years, although the credits can be recaptured if the housing project fails to comply with rent and income requirements.20

Tax credits, while benefiting investors and businesses, come with a downside cost: foregone taxation revenue, which, as noted above, cost the government US$59.1 billion in 2024. On the positive side, the LIHTC is estimated to crowd in US$2 of investment spending for every dollar in foregone revenue. The multiplier effect is even more staggering for municipal bonds, crowding in US$10 of private investor capital for each dollar in foregone tax revenue.21

What’s required to adopt the U.S. tax playbook in Canada

Investment tax credits and tax-free capital gains are not novel taxation concepts in Canada. The federal government’s Multiple Unit Rental Building (MURB) program, which ran from 1974 to 1981, permitted retail investors in rental apartments to lower their income tax obligations by claiming capital depreciation and other costs against their income. The program, which cost the federal government between $1.3 and $2.1 billion in foregone taxation revenue in today’s dollars, was eventually discontinued due to its ineffectiveness in creating below market rental housing and lowering rental construction costs.22

The U.S.’s LIHTC program is like Canada’s MURB program in providing tax incentives to attract private capital to finance affordable housing projects. But it differs in its prescriptiveness, governance, and tax-incentive design, which draws in more corporate and institutional rather than retail investor capital. By imposing thresholds for income and rent levels, along with a 15-year compliance period, the program has been successful in ensuring a steady supply of affordable rental housing that’s privately owned. The effectiveness of the program is further enhanced because states are given the flexibility to tailor the program to meet regional priorities, such as Washington state’s preference for projects that are located near mass transit.

Adopting the U.S. affordable housing taxation playbook in Canada will require all orders of government to tweak or introduce new legislative or governance changes in how they deliver and fund housing, and housing-related infrastructure. The greatest shift will be required at the local government level. There, long-standing capital budgeting practices will need to modernize to leverage debt financing that’s available from institutional investors.[1] The crowding in of private capital, however, hinges on the federal government making the necessary changes to its tax code, as the quantum of benefits of similar tax code changes at the provincial level are insufficient for investors.

Federal Government

The federal government would need to enact tax code and governance changes to implement a low-income housing tax credit and a tax-free municipal bond regime in Canada.

For tax-free municipal bonds, changes are required to the Income Tax Act to exempt interest earned on municipal bonds. Guardrails would be needed to ensure bond proceeds are earmarked for housing related infrastructure projects, such as watermains and sewers. To encourage green infrastructure, the government could also impose a requirement that proceeds be used to build low-carbon infrastructure, such as district energy systems using waste heat. Both guardrails could be achieved by defining the circumstances when interest earned on municipal bonds is not income. For these changes to work, municipalities would need to develop borrowing frameworks, such as a social debenture framework or a green debenture framework, which specifies how bond proceeds will be used.

Changes to the Income Tax Act would also be required to create an investment tax credit for the financing of affordable housing, along with corresponding eligibility criteria of what constitutes affordable housing. To encourage the construction of greener homes, the Department of Finance could replicate the IRS’s approach of defining a range and type of eligible projects.

The final broad change that may be required at the federal level is the expansion of the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s (CMHC) mandate to administer the income and rent limit elements of a LIHTC program, if its current remit related to core housing need does not include these activities.

Provincial Governments

Canadian provinces do not have housing financing agencies but could leverage housing ministries or departments to administer the provincial components of an LIHTC program. The mandate of these ministries and departments may need to change to encompass all provincial-level elements of a program, such as setting housing priorities, scoring applications, allocating tax credits, and monitoring compliance.

Municipal Governments

For decades, municipalities have been permitted to raise capital through bond issuances and loans to fund capital projects, but rarely for affordable housing.24 This is partly because the federal government along with the provinces are the key funders of market and non-market housing programs, aimed at housing affordability and more recently at climate change. Ontario is the only province where municipalities are actively engaged in funding affordable rental housing, mainly government-owned community housing.25 Funding for these initiatives is primarily paid for by revenue generated from municipal property taxes and user fees, and, in rare cases, municipal bonds, with the latter confined to the largest cities with a growing population and stable economic base, such as Toronto.

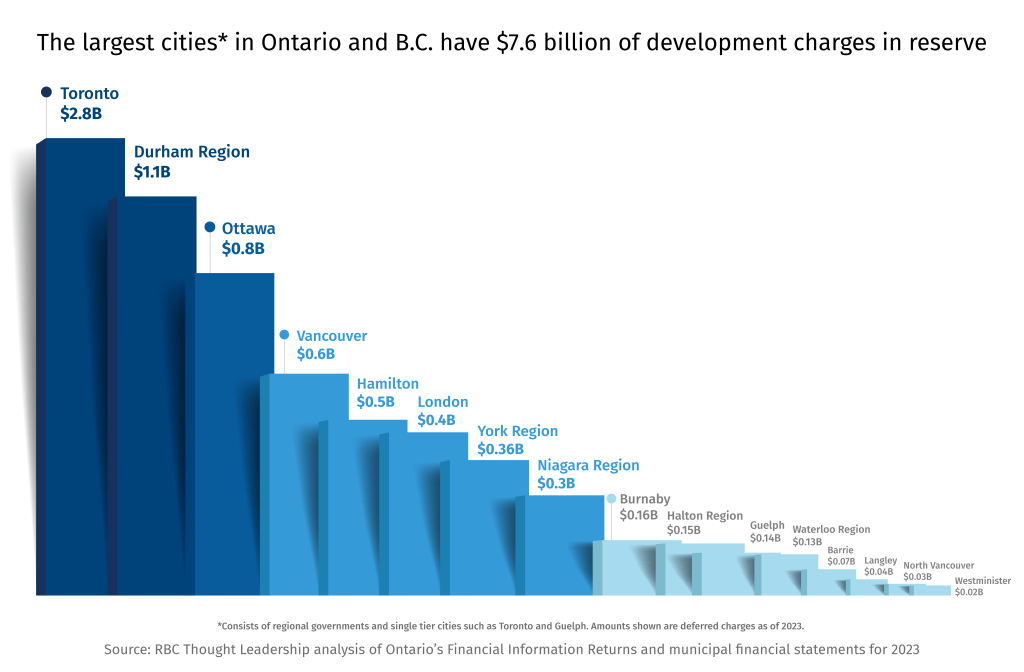

We are not proposing municipalities adopt the U.S. municipal bond playbook wholesale, whereby municipalities directly fund affordable housing with bond proceeds.26 Such a proposal may be unworkable in provinces that require public money to finance only public assets. Instead, we encourage municipalities, especially those in Ontario and B.C., to study the costs and benefits of paying for infrastructure with long-term public debt financing instead of development charges.27 Our analysis of proposed and under construction housing projects found that removing the cost of infrastructure from the price tag of homes can potentially reduce the per-unit construction costs of new homes in the Greater Toronto Area and Metro Vancouver by an average of 20%.28

Moving to a debt-financing model does not change who pays for housing related municipal infrastructure–renters, homeowners and ratepayers. The conduit for this cost pass-through however changes from developers to municipalities. Because municipalities can borrow at a cheaper rate than developers or homeowners, the interest costs that are passed through are lower.29 Fundamentally, the proposed change addresses a structural housing affordability problem that’s rooted in having renters and homeowners of new construction pay for infrastructure costs upfront, rather than spreading the cost over many decades, through monthly utility fees.

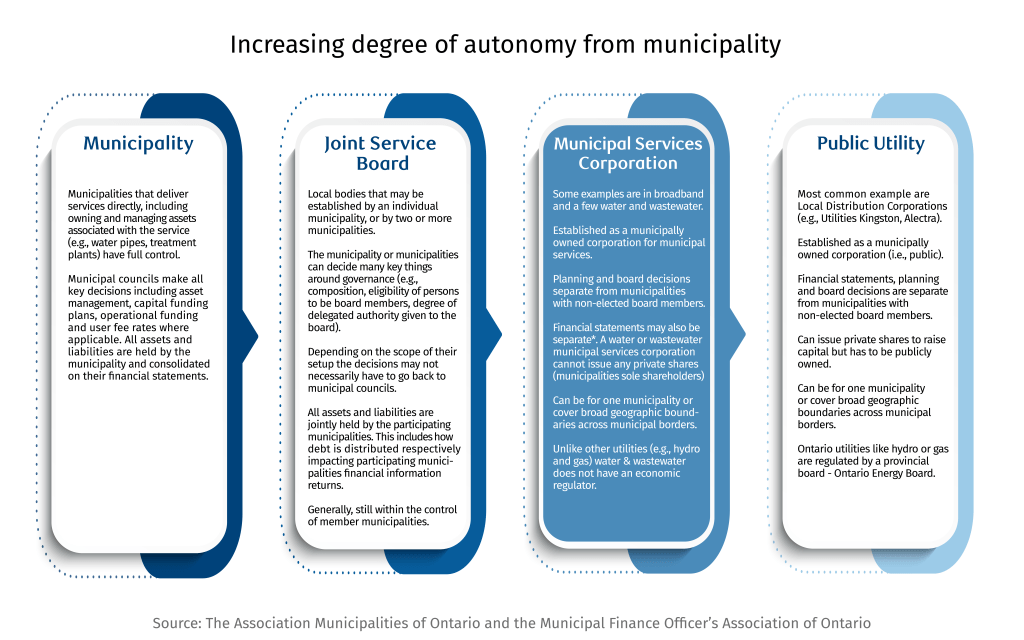

Public-debt financing can occur either as on-book or off-book financing. On-book financing requires municipalities to stay within their annual debt repayment limit, which is generally 25% of own revenue sources.30 Off-book financing provides municipalities greater borrowing flexibility, as annual debt repayment limits are not applicable.31 This form of financing, however, is more administratively complex, as municipalities would need to establish a municipal services corporation (MSC) or a public utility, and scope out the services they want to provide. The most common uses of MSC, or public utilities, are for water/wastewater and local electricity distribution. Both types of corporations operate arms-length from municipalities and take on the public debt used to finance an infrastructure project, in addition to owning and operating the asset.

The strong fiscal position of Canada’s largest municipalities indicates that shifting to a public debt model to finance housing related infrastructure is achievable. Based on regulatory filings32, the 13 largest single-tier and regional governments in Ontario that are also active in the municipal bond market have the fiscal room to take on at least $4 billion in debt, either as loans or bonds, without breaching their annual debt repayment limit. That’s two times greater than the $2 billion they collected in development charges in 2023.33

About 20 Canadian municipalities actively borrow from the public debt market to finance their hard infrastructure projects.34 Municipal bond issuances totaled $5.4 billion, in 2024, with $53 billion in outstanding debt.35

Given the mostly AA to AAA credit ratings of Canadian municipalities, the low risk of default, and the attractive risk-return profile, it’s likely that based on the U.S. experience,changes to the federal tax code to exempt the interest earned on municipal bonds will result in greater investor demand.36

While Canada’s municipal bond market is unlikely to grow 75 times, to $4 trillion dollars, which is the size of the U.S. municipal bond market, the $4 trillion figure is proof that tax incentives can be an effective tool in drawing in private capital into desired forms of infrastructure.37

Municipalities have a range of governance options in how to deliver their services, and ownership and management of these services. The most common model that exists in Canada are for municipalities to have full ownership of service delivery. Within the past 30 years, as more responsibilities are shifted onto municipalities from provincial governments, there’s been a slow evolution to explore different and more cost-effective forms of service delivery.

Municipal services corporations (MSC) and public utilities are the two most common alternative forms of service delivery.38 The creation of these arms-length municipally owned corporations provide greater flexibility to plan for and finance the full lifecycle of assets.

In a MSC or public utilities service delivery model, these corporations take on debt to pay for the upfront capital expenditure costs of an infrastructure project. Debts are paid off over several decades through monthly user fees derived from homeowners and businesses using the infrastructure. The continued economic viability of these systems is ensured through mandatory utility connections, typically required by provincial or municipal planning regulations.

Turning ideas into action

We encourage all levels of governments to study and consider the taxation and financing ideas proposed in this policy brief, as they refresh their housing strategies.

Our policy brief does not model the utility rates impacts were municipal governments to adopt a debt financing model for infrastructure. These economic and taxation studies are complex, requiring a deep understanding of capital budget and service delivery models, which is not uniform across Canada. Given the domain expertise required to execute these studies there’s an opportunity for provincial and municipal governments to jointly co-fund these studies to understand the costs and benefits of our proposed ideas.

At the federal level, policy and program design work is likely underway for the government’s affordable housing tax credit proposal, and its commitment to reduce municipal development charges by 50%.39 We encourage the Department of Housing, Infrastructure and Community to consider the ideas put forth, as they move deeper into the policy analysis, program design and consultation stage of their work. Since changes to the Income Tax Act are at the crux of our two ideas, we encourage the Department of Finance to evaluate the cost and benefits of our two tax proposals on the government’s balance sheet.

Conclusion

An estimated $2 trillion will be required over the next five years to build the additional 3.5 million homes required to alleviate the country’s housing affordability crisis.40 A crisis that in the past few years have led to several studies by the federal and provincial governments analyzing the root causes of the country’s housing supply and affordability problem, and recommendations for action.

The taxation ideas proposed above advance some of these recommendations. The Ontario Housing Affordability Task Force recommended the creation of an arms-length municipal services corporations that would build, own and operate housing related infrastructure.41 As well as finance the infrastructure using debt rather than development charges. And the Canada-British Columbia Expert Panel on the Future of Housing Supply and Affordability recommended increasing the supply of below-market rental housing through a long-term funding commitment.42

The urgency to leverage and enlarge the pool of capital available for new housing construction—five times the current level of deployment—is becoming greater, as provinces and the federal government take on unplanned new spending to support businesses and communities impacted by U.S. tariffs. The net effect on both levels of government is less fiscal room to support other priorities, including housing. Restoring housing affordability needs to be a short and long-term strategic priority for all levels of government. Doing so will free up household disposable income that can be re-invested to grow other sectors of the economy. It will be a sustainable outcome that can help safeguard today’s standard of living and economic prosperity for current and future generations of Canadian renters and homeowners.

For more, go to rbc.com/thoughtleadership

Download the Report

Contributors:

Myha Truong-Regan, Head of Research, RBC Climate

John Intini, Senior Director, Editorial

Caprice Biasoni, Graphic Design Specialist

Shiplu Talukder, Digital Publishing Specialist

The Great Rebuild: Seven ways to fix Canada’s housing shortage, from RBC Economics, examines the confluence of macroeconomic, demographic and policy factors that contributed to Canada’s affordability crisis.

This figure is based on Scenario 1 in the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) 2023 Canada’s Housing Supply Shortage: Restoring affordability by 2030 study. In this scenario housing affordability is restored to 2003-2004 levels, housing cost to income ratios range from 30% in many smaller provinces to a high of 44% in British Columbia. Scenario 2 would introduce a uniform housing cost-to-income ratio of 40%. In this scenario, an additional 2.27 million units of housing would be required, and only three provinces would be required to increase housing supply beyond current levels. These provinces are Ontario (1.63 million units), B.C. (0.62 million units), and Saskatchewan (0.02 million units).

Analysis based on RSM estimates using Freddie Mac data. The base case is 1.3 million units, annually, and an additional 400,000 units arising from new household formation. CMHC’s 3.5 million units are additional units required that are in excess of the existing annual housing completions, which averaged 195,000 between 2000 to 2022. For our analysis we prorated the 3.5 million units over 6 years, starting in 2025, for an annual average of 588,333 units. The population figure for the U.S. is 340 million based on April 2025 data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Canada’s population estimate of 42 million is from Statistics Canada, as of April 2025.

This is a weighted value for household incomes and home prices in the Greater Toronto Area and Metro Vancouver. Analysis based on data from the Canadian Real Estate Association, the Toronto Region Real Estate Board and CMHC’s Real Average Household Income (Before-tax) by Tenure report. Home prices are for Metro Vancouver and the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) as of April 2025. The average composite home price for Metro Vancouver was $1,184,500 and $1,107,463 for the GTA, and their weighted value is $1,147,276. The pre-tax household income in Vancouver was $127,500 and$137,400 in Toronto, and their weighted value is $132,635.

Latest available data as of June 2024 for the Apartment Construction Loan Program. To achieve the government’s goal of 131,000 units by 2031/32 requires the completion of an estimated 70,000 units by 2024, based on the assumption that an equal numbers of unit are built each year, and the first wave of units were completed in 2020, 3 years after the program was introduced. Data source: Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada – Progress on the National Housing Strategy – June 2024.

Government fees waived include land transfer tax and the federal portion of the harmonized sales tax. Downpayment support include the RRSP Home Buyers Plan and the Tax-Free Home Savings Account (FHSA). The Home Buyers Plan allows first time homebuyers to withdraw money from their registered retirement savings plan, without a tax penalty, if repayment is made within 15 years. The FHSA allows individuals to contribute to savings account where contributions are tax-deductible and withdrawals for first time home purchases are tax free. There’s a $40,000 limit to the FHSA.

The tax credit is aimed at the development of below market rental housing that’s privately owned, and not so-called community or social housing.

Analysis of data from the Congressional Budget Office; Cohn Reznick 2024 LIHTC Equity Market Volume Survey.

Between 60 to 70% of bond proceeds are used to fund municipal infrastructure and housing capital projects. Source: LSEG

Institutional investors that are pension funds are exempt from paying income tax on their capital gains, in both the U.S. and Canada. Pension funds invest in municipal bonds for two primary reasons: to diversifying their portfolio and obtain a low-risk steady cash flow. Retail investors are so called mom and pop investors.

Analysis by Charles Schwab found that the spread between taxable and tax-exempt municipal bonds as of February 2025 was 160 basis, and the 15-year average, since 2010, is 100 basis points. Provincial regulations require municipalities to create a reserve fund that is used to pay off debt issuances. While statistics on municipal debt default is not available in Canada, analysis by Fidelity Investments found a 0.04% default rate for U.S. municipal bonds. In comparison, the default rate for corporate bonds with similar risk profile was 1.44%.

These types of facilities are prescribed in section 142 of the tax code.

The per capita allocation for private activity bonds is $130, in 2025.

Based on 2022 data, which is the latest data available. Source: Novogradac.

Latest data available from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, for homes built between 1987 and 2022.

The 4% and 9% represent the amount of eligible costs that can be counted towards the low-income housing tax credits.

States generally impose another 15-year holding period on top of the federal requirement, bringing the overall affordability period to 30 years. The new equity investments are typically used to finance capital improvements. Banks in the U.S. are subject to the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), which requires them to serve the credit needs of the communities in which they do business, including low to moderate income neighborhoods. Investments in LIHTC deals are viewed favourably by banking regulators when evaluating a bank’s CRA performance.

RBC Capital Markets. The yield for a 12-month zero coupon US Treasury Bond is 412 bps on May 23, 2025.

The LIHTC provides a direct dollar-for-dollar reduction for federal tax liability. The credits provide investors with the flexibility to offset prior year’s federal tax liability. They can also be carried forward for 20 years if tax credit flow exceeds actual federal tax liability.

The 5 to 1 ratio referenced in the key takeaway is a weighted average of both tax incentives.

See Clayton Research Associates Limited CMHC sponsored study Tax Expenditures – Housing published in March 1981 and CMCH’s Assessment Report Evaluation of Federal Rental Housing Programs, published in 1988. The Clayton study was commissioned by CMHC to evaluate the costs, benefits, and effectiveness of select tax expenditures targeted at housing.

See C.D. Howe’s Could Do Better: Grading the Fiscal Accountability of Canada’s Municipalities, 2024 for analysis of budgeting practices across Canada Our proposal is also aligned with ideas put forth by Ben Dachis of Clean Prosperity in Utility financing of infrastructure to lower cost of housing and reduce emissions, and Michael Fenn of Strategy Corp’s Institute of Public Policy and Economy More Affordable Infrastructure: Tax-Free Municipal Bonds.

The approach used by municipalities to access the public debt market varies. B.C. and Quebec have provincial financing authorities who borrow from the debt market on behalf municipalities. A similar approach is taken in Ontario where regional governments exist. Regional governments borrow from the public debt market for their own needs and the needs of their constituent municipalities.

This funding relationship emerged in the 1990s when the Ontario government devolved responsibility of housing onto municipalities, in exchange for taking on responsibility for education.

The amount of bond proceeds used to fund housing varies from year to year. About 5% of outstanding issuances as of April 2025 are used to fund housing according to analysis by FTSE Russell.

Development charges, also known as capital cost charges, infrastructure charges or offsite levies are most common and the highest in Ontario and B.C. While development charges exist in other provinces to pay for growth related infrastructure, such as Alberta, they generally are a smaller proportion of total construction costs. Analysis based on data from the following sources: client data, BILD’s Comparison of Government Charges on New Homes in Major Canadian and U.S. Metro Areas, CMHC’s Housing Market Insight, July 2022, and scenario modelling using the City of Calgary’s building and development permit fee calculators.

This figure is a weighted average of development charges for single detach and row homes, and low and high-rise multi-unit residential buildings.

Developers borrowing costs is typically 100 basis points or one percentage above the prime rate. Residential mortgage rates are generally 200 basis points above the prime rate, exclusive of any promotional discounts. Using the latest prime rate of 4.95%, a developer’s cost of borrowing would be 5.95%, while for a homeowner, it would be 6.95%. Municipal bond borrowing costs range from 2.55% to 4.90%, for bonds issued in 2024.

The 25% threshold applies to municipalities in Ontario, BC, and Alberta. The City of Vancouver debt service ratio is limited to 10% of its own revenue sources, i.e., revenues from sources that it has direct control over, such as property taxes, user fees, and development charges.

Municipalities in Canada are required to establish a reserve fund for bond issuances. The reserve fund is used to pay interest payments and the principal outstanding. Monies required for the reserve fund comes from municipal operating budgets. The creation of reserve funds and risk-based lending practices is one of the reasons why municipal debt defaults are rare, in both Canada and the U.S.

Ontario Municipal Affairs and Housing’s Financial Information Returns.

Latest year of available data. Ontario municipalities collected $2.7 billion dollars in development charges in 2023 based on analysis carried out by the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing.

RBC capital markets.

Ibid.

Analysis by RBC Capital Markets found that 90% of municipal bond issuances in the U.S are single rated -A or higher.

Analysis of Federal Reserve data by Fidelity found that retail investors account hold 44% of municipal bonds and the balance is held by institutional investors and corporations.

See The Association Municipalities of Ontario and the Municipal Finance Officer’s Association of Ontario backgrounder on water and wastewater municipal services corporations.

Source: Liberal Party’s Building Canada Strong election platform commitments. Based on costing documents, the Federal government plans to spend $1.5 billion annually, over 4 years, on reducing development charges and supporting infrastructure.

Source: Liberal Party’s Building Canada Strong election platform commitments. Based on costing documents, the Federal government plans to spend $1.5 billion annually, over 4 years, on reducing development charges and supporting infrastructure.

Source: Liberal Party’s Building Canada Strong election platform commitments. Based on costing documents, the Federal government plans to spend $1.5 billion annually, over 4 years, on reducing development charges and supporting infrastructure.

Estimate based on a weighted average construction cost for single-detached, row/townhouse, low and high-rise multi-residential housing where construction is underway in the Greater Toronto Area. The calculation includes hard and soft construction costs, and land development costs, but excludes land purchase price, and fees, such as interest charges and management fees. In our analysis, per unit construction cost ranged from $462,000 to $577,000, and the weighted average development charges was 20%. The estimated development charges outlay is between $323 to $403 billion.

Recommendation 44 calls for the Ontario government to “Work with municipalities to develop and implement a municipal services corporation utility model for water and wastewater under which the municipal corporation would borrow and amortize costs among customers instead of using development charges”. Source: Report of the Ontario Housing Affordability Task Force.

Recommendation 17 calls for “the federal government make long-term funding commitments, as was done until the mid-1990s, rather than offering short-term capital grants.”

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.